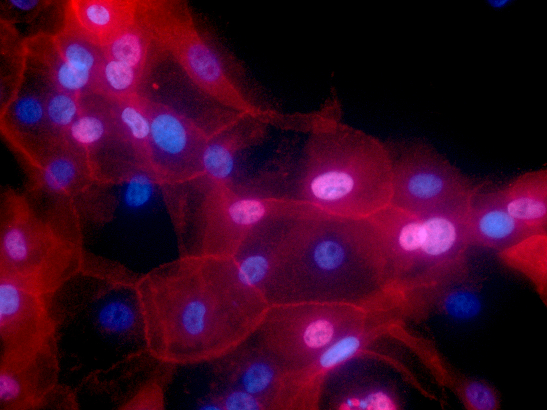

Image: Human breast cancer cells. Credit: Min Yu, NCI Cancer Close Up 2016 collection

A blood test can help identify rare mutations in advanced breast cancer, which may enable patients to access effective treatment more quickly in the future, Cancer Research UK-funded scientists have found.

As part of the plasmaMATCH clinical trial, the researchers were able to detect mutations in the DNA from the tumours, which had been shed into the bloodstream.

They found specific weaknesses in the breast cancer DNA that could be targeted with drugs, suggesting that this blood test could be a better way of guiding treatment than standard tissue biopsies, which can be painful.

The results were presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium today (Thursday). The trial was funded by Stand Up To Cancer, with additional support from AstraZeneca, Puma Biotechnology and Guardant Health.

Quicker and easier tumour testing

Researchers at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, analysed the blood from more than 1,000 women with breast cancer that had returned after treatment, or had spread to another part of the body.

They wanted to explore if taking a liquid biopsy, where traces of tumour DNA circulating in the blood can be detected, was a quicker and easier alternative to traditional tumour testing.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in the UK, with around 55,200 new cases every year, and women who are diagnosed later, or whose cancer has come back after treatment have limited treatment options. For example, when the disease is diagnosed at the latest stage, only 1 in 4 people (26 per cent) will survive their cancer for five years or more.

Scientists in our Division of Breast Cancer Research have been involved in some of the most famous discoveries in the history of breast cancer research. Learn how the ICR is tackling the most common type of cancer among women, which affects around one in eight women in their lifetime.

A small group of breast cancers that have acquired specific mutations, or genetic defects, may be directly targeted with drugs. However, these defects are rare, so it’s important to identify the patients who could benefit most.

Currently, these defects are identified by taking out a piece of the tumour using a biopsy or during surgery, a process that is invasive and comparatively slower.

These faults can also change after treatment or when cancer spreads, and in advanced cancer, it isn’t always possible to take further biopsies where cancer has spread. So, doctors may be working with an outdated picture.

Blood test to detect gene faults

The new study looked at whether a blood test could detect traces of faults in genes called HER2, ESR1 and AKT1, which are known to drive breast cancer.

They used information on these mutations to sort patients into four treatment groups with women with the AKT1 mutation further separated according to whether their breast cancer reacted to oestrogen. A total of 142 patients entered the treatment groups, with each group given targeted therapies against the specific characteristics of their cancer.

Five out of 20 women with the HER2 mutation and three out of 18 women with the AKT1 mutation responded to the targeted treatments neratinib and capivasertib, respectively. But the treatment targeting the ESR1 mutation was not considered effective enough.

To validate their findings, the researchers also checked tissue samples from the patients and confirmed that the liquid biopsy had correctly identified the presence or absence of the mutations in over 95 per cent of cases.

Crucially, DNA analysis of the physical tumours confirmed that the liquid biopsy had correctly identified the presence or absence of the mutations in more than 95 per cent of cases. The researchers say the blood test therefore suggests a robust way of identifying rare subtypes of breast cancer, and could replace the more invasive methods of analysing breast tumours.

‘Putting women on new targeted treatments matched to their cancer’

The researchers believe the liquid biopsies are now reliable enough to be used routinely by doctors, once they have passed regulatory approval. And for the targeted drugs still in development, the next step is to carry out larger clinical trials to assess whether they are better than existing treatments.

Professor Nicholas Turner, Professor of Molecular Oncology at the ICR, and Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden, said:

“The choice of targeted treatment we give to patients is usually based on the mutations found in the original breast tumour. But the cancer can have different mutations after it has moved to other parts of the body.

“We have now confirmed that liquid biopsies can quickly give us a bigger picture of what mutations are present within multiple tumours throughout the body, getting the results back to patients accurately and faster than we could before.

“This is a huge step in terms of making decisions in the clinic – particularly for those women with advanced breast cancer who could quickly be put on new targeted treatments matched to their cancer if it evolves to become drug resistant.”

Following her initial breast cancer diagnosis and successful treatment in 2012, Christine was shocked to discover that her cancer had spread to her brain in 2018. Thanks to palbociclib, Christine is now living well with cancer, including a new-found passion for cycling.

‘Potential to speed up access to effective treatment’

Professor Judith Bliss, Professor of Clinical Trials at the ICR and Director of its Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit, said:

“We designed this study to look at several targeted treatments within a single trial platform. This setup has enabled us to study these multiple rare mutations effectively and quickly, reporting the results of the trial within only three years since the study started.

“These kinds of efficient clinical trial designs are key in cutting down the time it takes for new targeted treatments to reach patients.”

Dr Emily Farthing, Senior Research Information Manager for Stand Up To Cancer, said:

“It’s exciting to see that blood tests have real potential to help speed up access to effective treatment for people with advanced breast cancer. Stand Up To Cancer funds translational research like the plasmaMATCH trial, which transforms discoveries in the labs into new tests and treatments that will make a real difference for people with cancer.

“More than £62 million has been raised in the UK to date, which has funded over 50 clinical trials, so we look forward to seeing more breakthroughs in the future.”