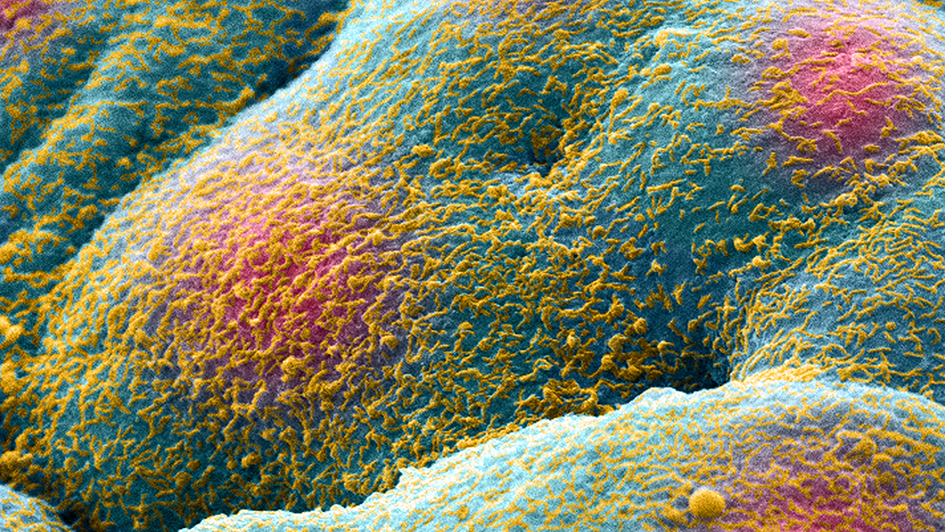

Image: False-coloured, high magnification, scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of a three dimensional multi-cellular prostate tumour spheroid (cluster of cells). Credit: Izzat Suffian, David McCarthy & Khuloud T. Al-Jamal. License: CC BY 4.0

Discovery could help inform future testicular cancer screenings

Our first news on male cancers in the past year was from a study led by scientists here at The Institute of Cancer Research. They showed that testicular cancer in families is usually caused by the accumulation of minor genetic changes that have only a small effect on their own, but together can add up to a significant risk.

The important study showed that a mixed set of common, single-letter changes to the DNA code, each of which slightly increase a man’s risk of testicular cancer, plays the biggest role in causing the disease – rather than lifestyle factors, or small numbers of major genetic mutations that each have a big impact on risk.

Study leader Professor Clare Turnbull, Team Leader in Molecular and Population Genetics at the ICR, said:

“Our study uncovers the genetic basis for familial cases of the most common type of testicular cancer, and represents an important step forward in our understanding of the disease.

“In the short term, our discovery will help in counselling men who might be worried about their risk of developing testicular cancer. In the longer term, it could help inform future screening programmes for testicular cancer that might diagnose it earlier.”

Changing the shape of targeted therapy

In February we shared news about a new way to plan radiotherapy that could help shape treatment away from sensitive organs near tumours to reduce side-effects.

The technique was developed by physicists at the ICR and our partner hospital, The Royal Marsden, and involves using complex mathematical formulae to spare sensitive organs from radiation damage.

Study leader Professor Uwe Oelfke, Head of the Joint Department of Physics at the ICR and The Royal Marsden, said:

“Radiotherapy is a very effective treatment for cancer, but the damaging effect of radiation on healthy tissue can lead to challenging side-effects that can affect a patient’s quality of life. Treatment margins are necessary to ensure the whole tumour is targeted, but a safe reduction of these margins is key to further improving outcomes for patients.”

New genes linked to prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness

In April we revealed that a new panel of genes could identify men at highest risk of aggressive prostate cancer.

The study was the largest of its kind so far, both analysing all known DNA repair genes, and including a comparison with healthy men to determine the effect of gene changes on prostate cancer risk.

Our wide-ranging programme of prostate cancer research is helping men to live longer, improving their quality of life and increasing cure rates.

In the future, the panel could be developed into a test for use in screening services so that high-risk men could be closely monitored, increasing the chance of catching the disease early.

Professor Ros Eeles, Professor of Oncogenetics at the ICR, said:

“At the moment, men can receive a diagnosis of prostate cancer without really knowing how the disease is likely to affect them, but in future a test could pick out those who are likely to develop aggressive disease and need intensive treatment.

“Testing for genes linked with aggressive prostate cancer could be especially helpful for informing treatment decisions in men already diagnosed with the disease.”

Exciting new treatments for prostate cancer

During the ASCO 2019 cancer conference, we shared news about how olaparib, a pioneering gene-targeted drug already licensed for breast and ovarian cancer, can also benefit some men with prostate cancer.

The results showed the benefits of olaparib, which is from a family of drugs called PARP inhibitors, for men with prostate cancer and DNA repair defects in their tumours.

Dr Nuria Porta, Principal Statistician on the TOPARP-B trial in the Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit at the ICR, said:

“Our trial shows that PARP inhibitors could be effective in some men with prostate cancer – potentially widening out their use beyond ovarian and breast cancer.

“We also found that these drugs could be effective in men with several different DNA repair mutations, and in men with genetic faults in their tumours rather than just the smaller group of men with inherited mutations.”

A pill without the side-effects of chemotherapy

At September’s European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress, we announced further news about olaparib.

The drug was shown to be more effective than modern targeted hormone treatments at slowing progression and improving survival in some men with advanced prostate cancer, according to the findings of a phase III clinical trial called PROfound.

Professor Johann de Bono, Regius Professor of Cancer Research at the ICR and Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, who co-led the PROfound trial, said:

“Our clinical trial shows that olaparib, a pill without the side-effects of chemotherapy, is able to target an Achilles’ heel in cancer cells. Olaparib is able to kill cancer cells with faulty DNA repair genes while sparing normal cells.

“This study is a powerful demonstration of the potential of precision medicine to transform the landscape for patients with the commonest of male cancers.”

The role of gut bacteria and radiotherapy side-effects

Last month a new study showed that taking a ‘fingerprint’ of the mix of bacteria in the gut can indicate how susceptible individual cancer patients are to gut damage as a result of radiotherapy for prostate and gynaecological cancers.

The research is the first to explore the protective effects of the microbiome in prostate cancer patients and at preventing the late effects of radiotherapy.

Professor David Dearnaley, Professor of Uro-Oncology at the ICR and Consultant Clinical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden said:

“Our study is the first to show that gut bacteria have an important influence on how susceptible patients are to gastrointestinal side effects from radiotherapy. If microbial treatments such as faecal transplants are found to reduce damage, for example, it could substantially improve patients’ quality of life.”

Our Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery

We are building a new state-of-the-art drug discovery centre to create more and better drugs for cancer patients, including for male cancers.

The centre is a £75m project – and we now have less than £14m to raise. To make our building a reality, we urgently need your philanthropic support.