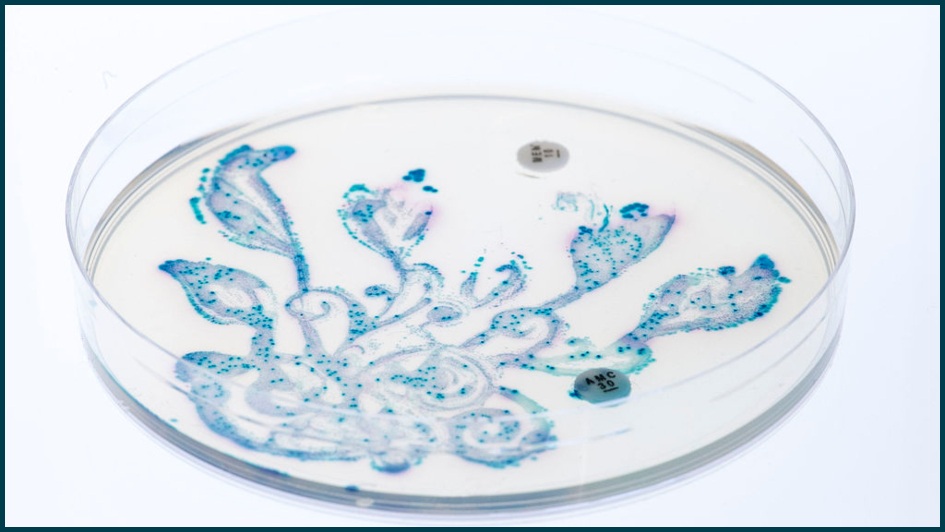

Image: Wild garden of the gut bacteria. Image credit: Nicola Fawcett. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Taking a ‘fingerprint’ of the mix of bacteria in the gut can indicate how susceptible individual cancer patients are to gut damage as a result of radiotherapy for prostate and gynaecological cancers, a new study shows.

Researchers showed that having a reduced diversity of gut bacteria was associated with an increased risk of both immediate and delayed damage to the gut following radiotherapy.

If patients at higher risk of gut side effects could be identified before radiotherapy, they could be given procedures such as faecal transplants to treat or even prevent damage.

Taking the bacterial fingerprints of patient's guts

A team at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London studied the bacterial fingerprint and faecal samples of 134 patients at different stages pre and post radiotherapy to the prostate and pelvic lymph nodes.

Their study, published today (Wednesday) in Clinical Cancer Research, aimed to see if there was a difference in the combination of gut bacteria among patients who suffered gut damage following radiotherapy compared with those who didn’t.

The research was funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

The role of gut bacteria and radiotherapy side-effects

The gut microbiota contains the largest number of ‘good bacteria’ in the human body, playing a vital role in helping digest food and keep the digestive system healthy. Each person has a different bacterial microbiome that is unique to their gut, like a bacterial fingerprint.

The researchers were interested in assessing the role the microbiota plays in patients’ response to radiotherapy – given that around 80 per cent of patients report a change in bowel habit after pelvic radiotherapy, and that 10 to 25 per cent have significant, long-term damage to their gut which impairs their quality of life.

Damage to the gut can often lead to bleeding, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea and weight loss, and can occur both early (during or shortly after radiotherapy), or late (from around three months afterwards).

The researchers found that patients who had a high risk of gut damage had 30–50 per cent higher levels of three bacteria types, and lower overall diversity in their gut microbiome, than patients who had not undergone any radiotherapy.

This suggests that patients with less diverse gut microbiomes and high levels of the bacteria – Clostridium IV, Roseburia and Phascolarctobacterium – are more susceptible to gut damage.

The researchers also believe these patients may require more ‘good bacteria’ to maintain a healthy gut – and so may be more susceptible to side effects when these bacteria are killed by radiation.

How gut damage could be prevented

The new research is the first to explore the protective effects of the microbiome in people and at preventing the late effects of radiotherapy. The next stage will be to explore whether it is possible to treat or prevent gut damage in people with high-risk microbiome fingerprints – potentially by giving them faecal transplants, or by altering the dose of radiation given.

Professor David Dearnaley, Professor of Uro-Oncology at the ICR and Consultant Clinical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden said:

“Radiotherapy to the prostate and pelvic lymph nodes is an important way to manage cancer but it can result in damage to the gut and unpleasant side effects for the patient, which can often be long-lasting and quite severe.

“Our study is the first to show that gut bacteria have an important influence on how susceptible patients are to gastrointestinal side effects from radiotherapy. We still need to do further studies to confirm the role of good bacteria, but if we can identify patients at the highest risk of gut damage we could intervene to control, treat or even prevent the side effects of radiation. If microbial treatments such as faecal transplants are found to reduce damage, for example, it could substantially improve patients’ quality of life.”