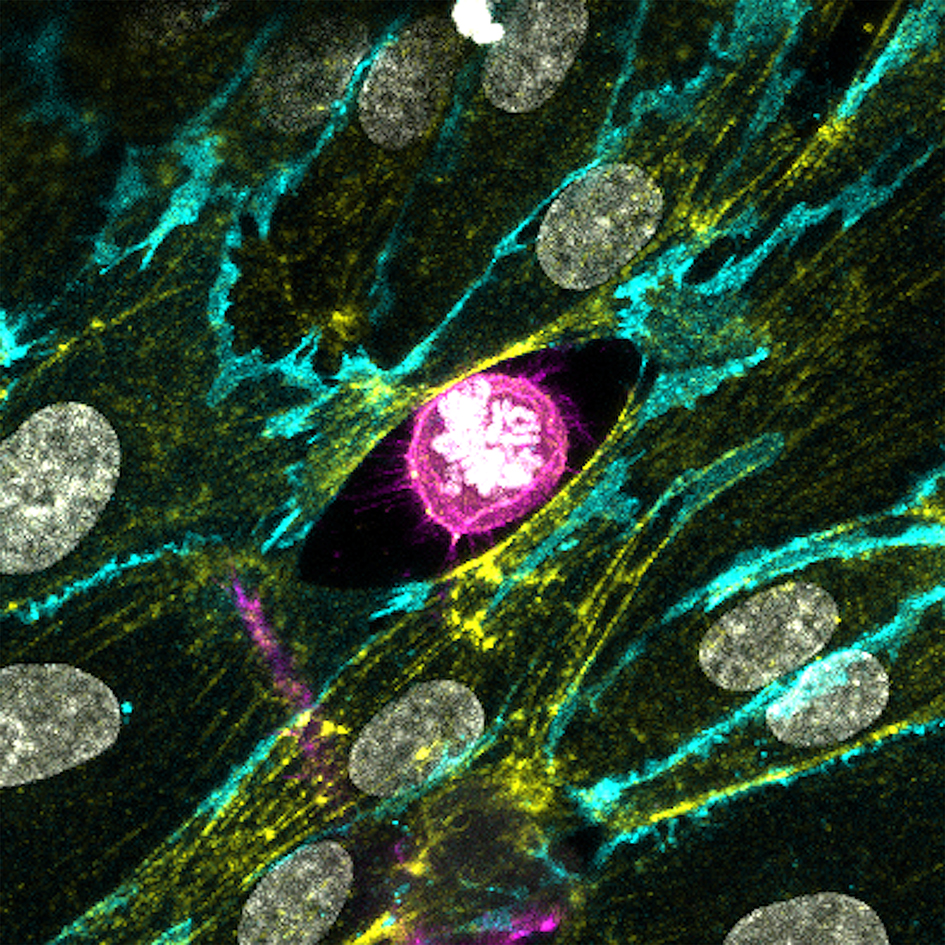

Image: The winning image by Dr Maxine Lam showing a replicating cancer cell as it invades through blood vessels

Each year, The Institute of Cancer Research runs a Science and Medical Imaging Competition – designed to cater for the moments in the lab or the clinic where science meets art.

The entries we receive for the competition have all been created in the course of our pioneering cancer research – but they are also exceedingly beautiful, and wonderfully effective at conveying broad messages about our work.

‘Divide and conquer’

The winner of this year’s competition - ‘Divide and conquer’ by ICR postdoc Dr Maxine Lam – is a great example. It shows a replicating cancer cell in vivid detail as it invades through blood vessels – and communicates something about the lethal process of cancer metastasis that words alone often struggle to convey.

Metastasis is one of the most challenging aspects of cancer, because it often makes the difference between life and death. Once cancer has spread to other parts of the body we have few effective treatments, and the disease is often fatal.

Scientists are therefore keenly interested in understanding how cancer cells spread so they can find ways of stopping it from happen.

And that has led to the development of ever more sophisticated and powerful imaging technologies so researchers can watch the process in action over time.

“I’m really excited and honoured to have won”

Dr Lam’s winning image was taken using a technology called confocal microscopy, and shows a cancer cell in pink invading through a layer of blood vessel cells, in yellow and cyan. The cancer cell has created a gap in the layer of blood vessel cells as it invades.

The picture illustrates a key step in metastasis called extravasation – where cancer cells move out of a blood vessel into tissue to spread to secondary tumour sites. Despite the importance of this step, very few models exist in the lab to directly visualise and understand it.

Dr Lam’s lab in the ICR’s Division of Cancer Biology uses a unique set-up to provide previously unseen detail into this process.

In the image white DNA inside the cancer cell has condensed into bright rods. This means that the cancer cell is in the process of dividing itself, even as it is invading – a remarkable yet terrifying sight. Dr Lam’s lab is using images like this to identify factors that could prevent cancer cells from being able to move and spread.

Dr Lam said: “I’m really excited and honoured to have won the ICR Science and Medical Imaging competition. This image captures two important moments in the life of a cancer cell, when it divides to make new copies of itself and when it leaves the circulation and invades new tissues, which is one of the most dangerous aspects of cancer.

“Seeing this process in action helps us to better understand how cancer spreads, and I hope this will help with developing new treatments.”

The public’s favourite

Dr Lam’s image was awarded the main prize in the competition by a panel of judges from the ICR and our partner hospital The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust.

We also this year carried out our first ever public vote, asking our supporters on social media to choose their favourite from the judge’s shortlist.

There was lots of agreement between the judges and the public, but the vote picked a different winner – a stunning time-lapse image of a breast cancer cell on the move by PhD student Patricia Pascual Vargas.

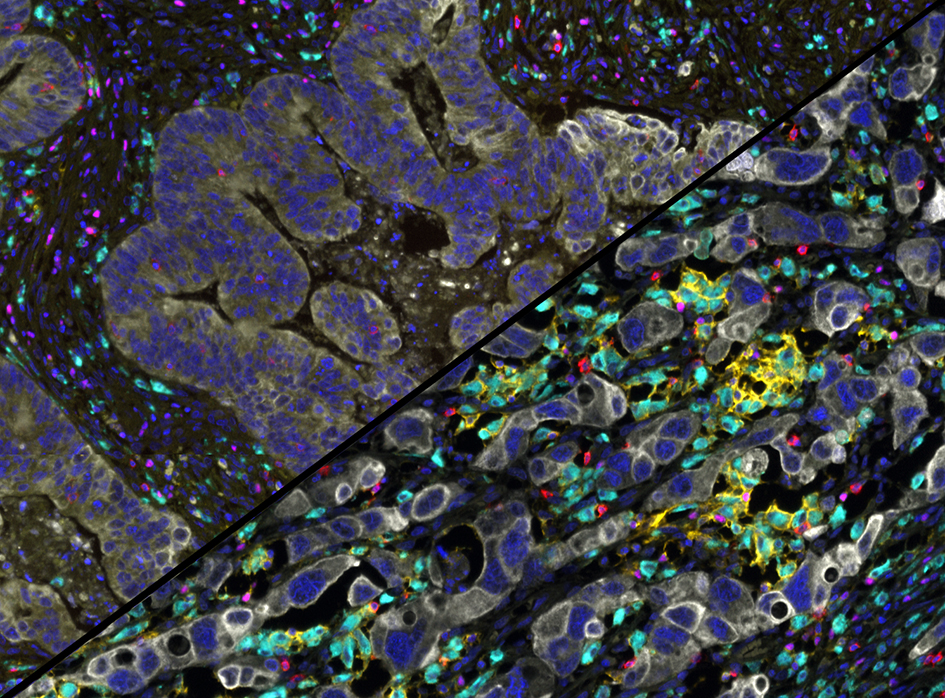

Patricia Pascual Vargas' photograph: Time-lapse image of a breast cancer cell on the move

Cancer cells can take on many shapes, squeezing through tissues and finding their way into places they shouldn’t be, using a complex network of adhesion molecules on their surfaces to move around.

Patricia’s image was taken using another type of technology called a total internal reflection fluorescence microscope (TIRF), and shows a very aggressive type of triple-negative breast cancer cell sensing its environment, by making contact through structures called focal adhesions.

This time-lapsed image uses different colours to show the position of focal adhesions over time. The yellow and red colours represent shorter adhesion times, and show that the cell is moving down and to the left.

Patricia and her colleagues are looking at how targeting certain genes affects the formation of adhesions, changing the cell’s shape and how it moves. It could be possible to prevent cancer cells from spreading around the body, making cancer easier to treat.

Patricia said: “I’m thrilled to have won the first ever public vote. My image helps to demonstrate that cancer cells aren’t static – they move and change shape, and this important characteristic helps them to adapt to their environment. By pinpointing how cancer cells do this we could prevent them from changing shape and stop them from spreading, which could save patients’ lives.”

Our fantastic shortlist

With another year of so many astounding entries, it’s important to recognise all of the fantastic images that made it onto our shortlist.

Dr David Mansfield

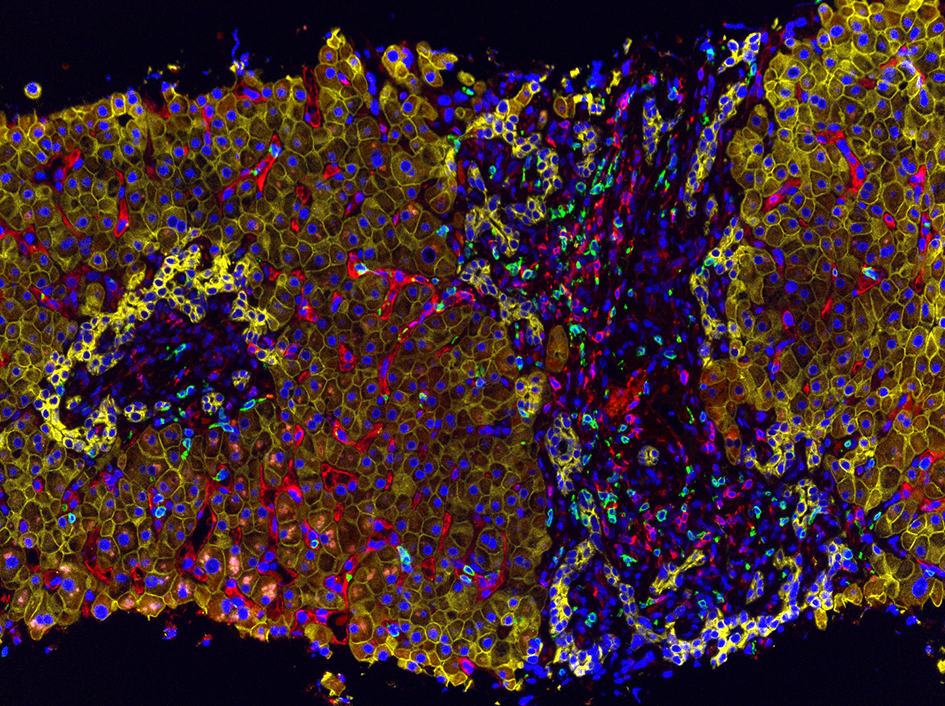

Cell death caused by radiotherapy – before and after, taken by Dr David Mansfield, Division of Radiotherapy and Imaging.

David Mansfield's photograph: Cells within a tumour visualised before (left) and after (right) radiotherapy

This image shows cells within a tumour visualised before (left) and after (right) radiotherapy. Coloured immune cells move in to clear up the tumour cells in white, left behind after treatment. This helps the body gain vital anti-tumour immunity and long-term protection from recurrent disease.

Multiple members of the Clinical Studies Division

Detecting immune cell populations in a liver biopsy by Dr Mateus Crespo Dr Bora Gurel, Ana Ferreira, Rita Pereira, and Professor Johann de Bono, Division of Clinical Studies.

Photograph by multiple members of the Clinical Studies Division: Detecting immune cell populations in a liver biopsy

This multi-coloured image was taken using multiplex immunohistochemistry to light up a liver biopsy from a patient with metastatic cholangiocarcinoma, an aggressive cancer of the bile duct. Liver cells in yellow are being infiltrated by immune system T-cells in red and green.

Parames Thavasu

The exploding nuclei – using combination drug treatments to overcome DNA damage repair mechanisms in cancer cells, by Parames Thavasu, Division of Cancer Therapeutics.

Parames Thavasu's photograph: cells of an aggressive form of breast cancer called triple-negative breast cancer

This image shows cells of an aggressive form of breast cancer called triple-negative breast cancer, which is difficult to treat and has poor outcomes. After treating with a drug combination that causes damage to DNA at different stages of cell division, 'explosive' damage to cancer cells has occurred.

Dr Rebecca Marlow

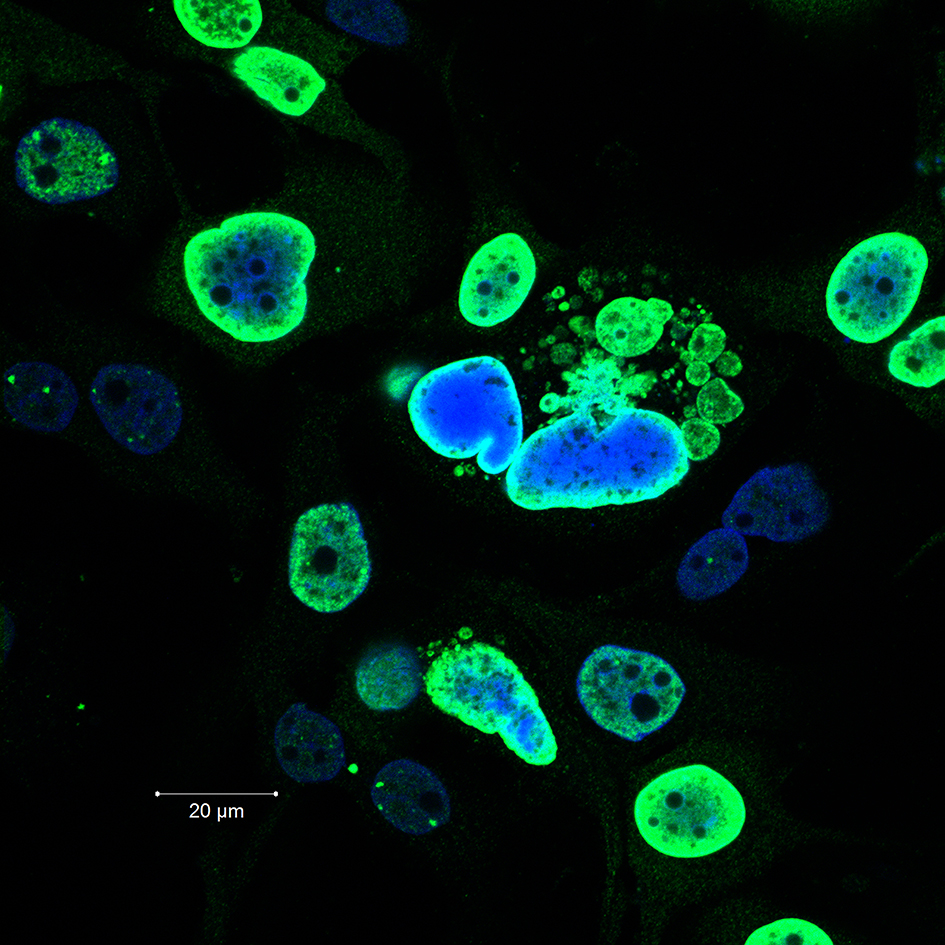

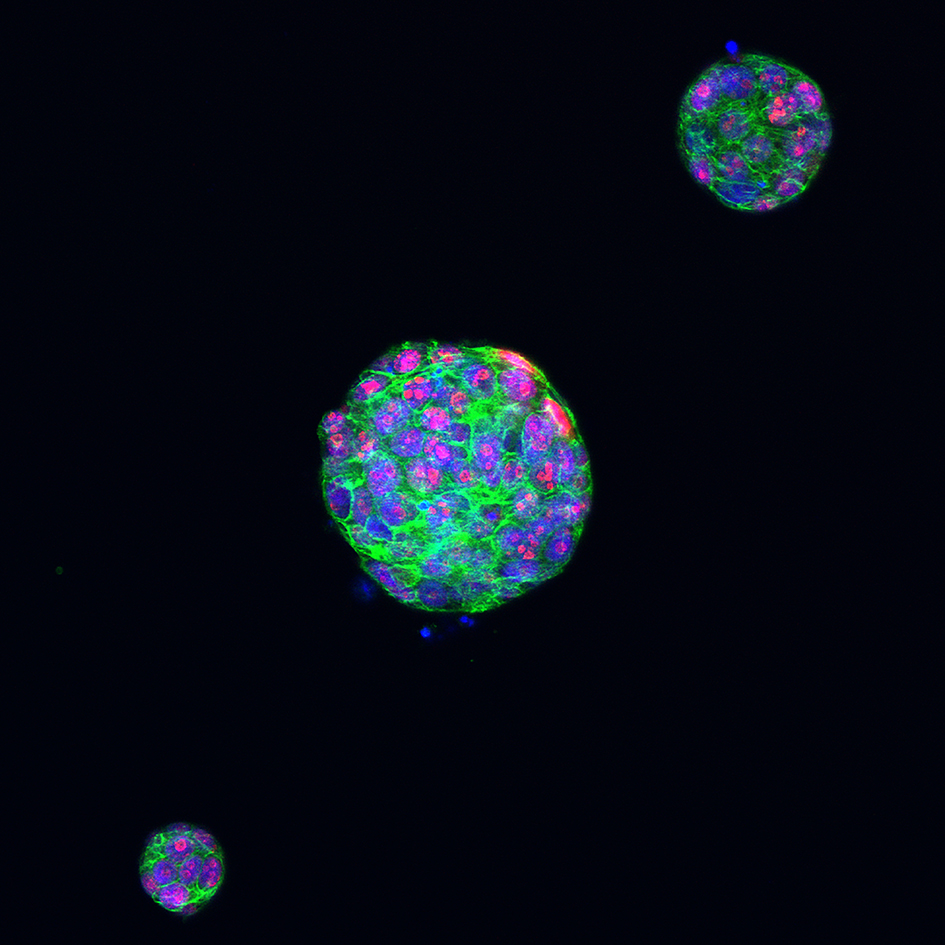

Proliferating cells in a tumour organoid of triple-negative breast cancer, by Dr Rebecca Marlow, Division of Breast Cancer Research..

Dr Rebecca Marlow's photograph: Proliferating cells in a tumour organoid of triple-negative breast cancer

This image shows tumour organoids of triple-negative breast cancer, a hard-to-treat form of the disease, grown from tissue samples donated by patients.

The nuclei of cells are marked in blue, while the cytoskeleton that helps cells maintain their shape is green. Proliferating cells are pink, where cells in the organoid are growing and dividing.

Cutting-edge research

These eye-catching images illustrate just some of the cutting-edge research being carried out at the ICR, taken using sophisticated equipment purchased thanks to generous donations from our supporters.

From images like these our researchers are gaining unprecedented insights into the mechanisms that drive cancer, and new ways to target the disease to help treat patients.

Dr Chris Bakal, who leads the teams in which Maxine and Patricia work, and is a previous winner of the competition himself, said:

“It is a cancer’s ability to spread round the body which often makes it fatal. It is incredibly valuable to be able to image this process over time to give us the insights into cancer biology that we need to discover new treatments.

“Our winners have used cutting-edge imaging technology to create measurable, single-cell imaging in 3D environments, to provide a vivid picture of exactly how cancer cells metastasise.”