Breast Cancer Now-funded researchers have discovered that genetic mutations which promote resistance to a particular type of cancer treatment can be present in breast cells before breast cancer has developed.

This novel finding could explain why some patients develop resistance to treatment so rapidly in the clinic, and highlights new strategies that could be used to circumvent this common problem.

One of the main challenges when treating cancer in the clinic is known as ‘acquired resistance’, meaning that the cancer develops resistance to a drug after being exposed to it, rather than already being resistant before treatment begins. Acquired resistance can occur very quickly after treatment begins in some patients.

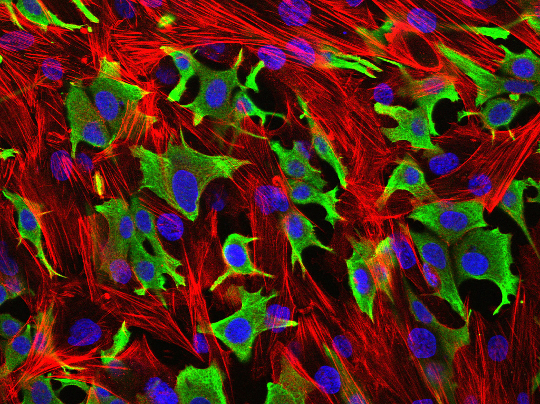

The researchers, based at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, set out to look into how cancer cells may develop resistance to MPS1 inhibitors, a new type of cancer drug currently in development for many cancer types, including breast. They discovered five separate mutations within the MPS1 gene that all cause resistance in cancer cells.

These five genetic mutations were also found at a low frequency in primary breast tumours as well as in normal, healthy breast tissue cells – which suggests that resistant mutations to MPS1 inhibitors pre-exist naturally in the breast. This discovery provides the potential to allow identification of patients likely to experience resistance as early as possible, helping to more accurately guide treatment decisions for each patient.

In addition, because different inhibitors remain effective against distinct mutations the results suggest that using a variety of inhibitors targeting the same gene, either in combination or one after the other, might work to combat the development of resistance.

Importantly, the team also discovered that the most common genetic mutation that causes a patient to be resistant to a drug belonging to another class of cancer treatments – the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) inhibitor, gefitinib – is also present in healthy breast tissue cells. This suggests that the discovered mechanism of acquired resistance may be crucial for understanding resistance to a variety of drugs in different type of cancers, including breast cancer.

Study leader Dr Spiros Linardopoulos, Team Leader in Drug Target Discovery at the ICR, said: “Our study shows that the genetic mutations which drive resistance to some targeted cancer drugs are present in cells right from the beginning of treatment – and are even found in healthy cells.

“It’s an important discovery because it proves that drugs can act as an evolutionary force on tumours by killing susceptible cells but leaving resistant cells alive – in a process that’s been called the ‘survival of the nastiest’. It shows that clinical trials of new targeted drugs need to be planned carefully, as in many cases treatment will select for mutations that make the cancer resistant.”

Katherine Woods, Senior Research Communications Manager at Breast Cancer Now, said: “These are really exciting findings – not only does it reveal novel mutations for drug resistance but also adds weight to the idea that those mutations which eventually result in acquired drug resistance exist prior to treatment.

"The development of resistance to cancer therapies is a huge challenge in the clinic. As we learn more about how acquired resistance emerges, in particular the specific genetic mutations that cause it, we move closer towards being able to select the most effective drug combinations for each patient.

“It’s really important that we continue to find ways to counteract drug resistance if we are to make best use of the drugs we have available and improve the outlook for breast cancer patients, taking us closer towards our ambitious goal of stopping women dying from this devastating disease by 2050.”

Dr Emma Smith, Senior Science Information Officer at Cancer Research UK, said: “Understanding how cancer becomes resistant to therapy is still one of the biggest challenges facing researchers, and this study sheds some light on possible ways cancer cells evade treatment. But most of the research was carried out on cells grown in the lab, so further work is needed to uncover the role these genetic mistakes play in patients and if anything can be done to stop cancer becoming resistant in this way.”

The research was published in Cancer Research and funded by Breast Cancer Now and Cancer Research UK. The work was carried out at Breast Cancer Now’s research centre and the Cancer Research UK Cancer Therapeutics Unit, both based at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR).

Breast Cancer Now is the UK’s largest breast cancer charity, created by the merger of Breast Cancer Campaign and Breakthrough Breast Cancer.