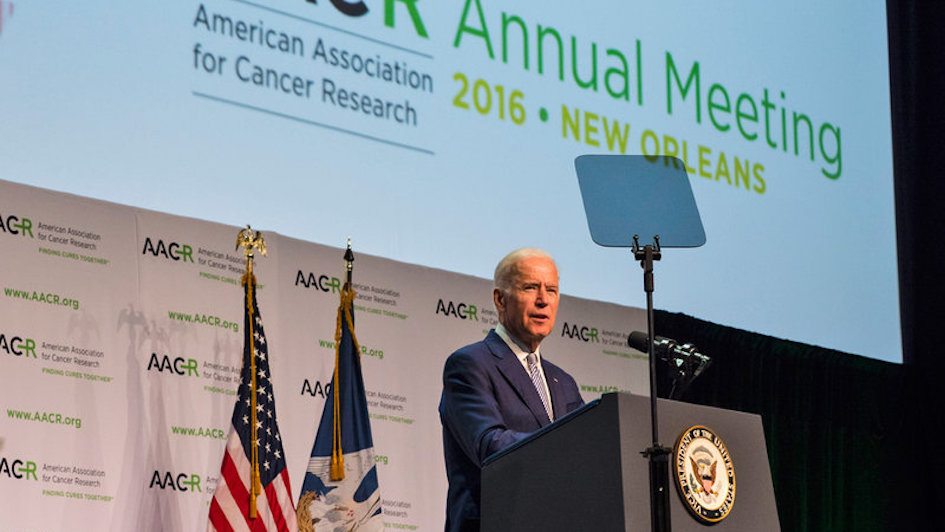

Vice President Joe Biden addresses delegates at the AACR cancer conference. Credit: AACR/Todd Buchanan.

‘We are at a turning point in cancer research.’ That was the rousing message of the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2016, which took place last month.

This year’s conference in New Orleans was the biggest ever with more than 19,000 delegates attending talks, forums, workshops and poster sessions over five days.

As scientists reflect on the 6,000+ research abstracts presented during the conference, there’s a lot to digest, but some exciting themes have emerged.

Collaboration

The AACR has worked closely with US Vice President Joe Biden on his National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, which aims to remove barriers to research to accelerate progress in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cancers.

The initiative will fund $1billion dollars of cancer research, but key to improving outcomes for more cancer patients will be better research collaboration.

The biggest challenges in cancer research will only be defeated by multidisciplinary teams of scientists working together towards a common goal. This sort of scientific collaboration is at the heart of much of our research here at The Institute of Cancer Research in London, as was recognised in a recent report from the Academy of Medical Sciences. But more must be done.

ICR PhD student Lizzy Coker attended AACR 2016 and heard how collaboration was key to filling in the major gaps in our knowledge about the genetics of cancer.

She said a recurring comment from speakers was that precision therapies targeting specific cancer-causing mutations are available for only a tiny percentage of patients, because we know so little about less common mutations or forms of cancer.

Project GENIE (Genomics, Evidence, Neoplasia, Information, Exchange) is a new collaboration tool which could be particularly useful for rare cancers.

Project GENIE will build a database linking genomic profiling data from tens of thousands of cancer patients treated at multiple international institutions with their clinical outcomes, which could identify novel cancer-causing proteins that could be targeted by drugs, or mutation signatures that predict sensitivity to certain treatments.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a new way to treat cancer that uses the patient’s own immune system to destroy tumours. It was a real buzz topic this year, with many delegates having to stand in the aisles to hear about the latest immunology advances.

One study described as ‘game changing’ was a clinical trial of the antibody nivolumab, which is the first immunotherapy to improve survival for patients with head and neck cancer.

Nivolumab works by targeting a protein on the surface of immune cells called PD-1, which prevents the immune system from damaging healthy cells. Cancer cells can interact with PD-1 to hide from the immune system, so blocking this interaction helps our immune cells target cancer.

Preliminary results from the trial, which is led in the UK by the ICR’s Professor Kevin Harrington, have shown that 36% of patients with head and neck cancer treated with nivolumab were still alive one year later, compared with 17% of patients treated with chemotherapy.

Immunotherapy drugs like nivolumab can also be combined with radiotherapy to achieve impressive results.

Dr Irene Chong, a Clinician Scientist at the ICR, and a Consultant Clinical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden Hospital, attended a session that showed combining treatments called immune checkpoint inhibitors with radiation therapy led to big reductions in tumour size for a group of patients with metastatic melanoma.

Genomics

The genome-editing tool CRISPR is revolutionising cancer research, and was another hot research topic at the conference this year.

This powerful technique allows scientists to accurately delete any region of the genome to see how it plays out on cellular biology, which could help identify genes to target with new cancer drugs.

Before CRISPR, the only way to know the effects of a genome mutation was to study mice bred specifically for the fault, which could take months or years. Now, researchers can use human cells, and study multiple deletions at the same time, providing the answers in weeks.

Dr Chong attended sessions discussing the prospects and challenges of genome editing using CRISPR technologies – including whether it could be used directly as a treatment. The session discussed examples of successful treatment strategies using genome editing carried out in cell cultures and in mice, but concluded that this technology would require further optimisation to improve its accuracy and safety for patients.

The conference ended with an address from Vice President Biden outlining his plan to revolutionise cancer research in the US. His multi-faceted initiative includes improvements to processes for gaining grants, publishing research and accessing data, plus additional computational infrastructure.

Biden’s speech was warmly received, particularly his statement: ‘We want to enable scientists to do science.’

It’s only through more research that we will defeat cancer, so let’s hope the findings coming from AACR 2016 take us closer to that goal.