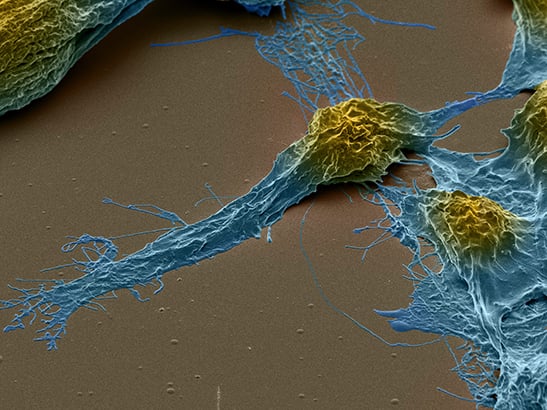

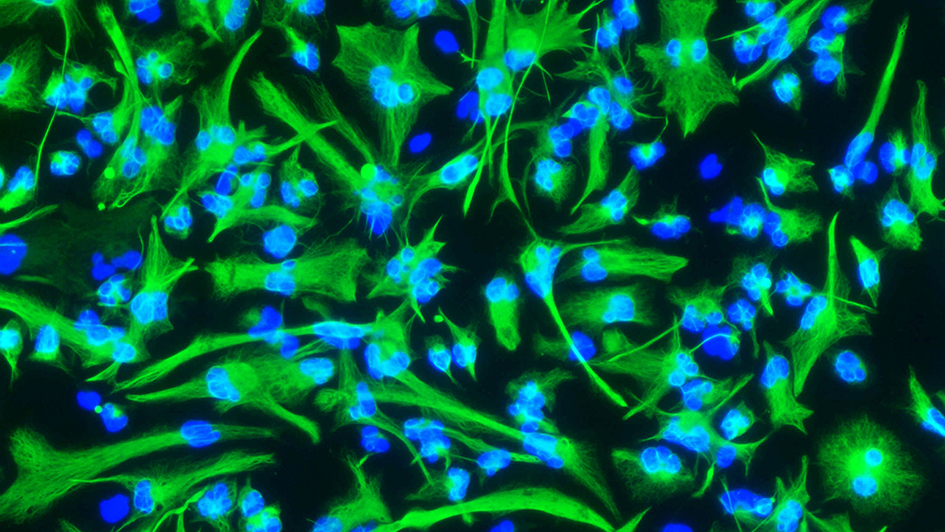

Image: Astrocytes derived from brain cancer stem cells in culture. Credit: Steven Pollard. License: (CC BY 4.0)

Despite many years of excellent research to improve our scientific understanding of cancer, and great progress in improving the survival of many types, brain tumours have remained a particularly tough nut to crack.

Only 14 per cent of patients with brain cancer survive for five or more years after being diagnosed – a number that has improved little over the last 40 years.

A key reason for this is that we’re simply not discovering and developing enough innovative new treatments for brain cancers. Indeed, here at The Institute of Cancer Research we released a major report on drug access in December which found among other things that no new brain cancer drugs at all were licensed by the European Medicines Agency between the years 2000 and 2016.

It was to address this lack of progress that last year we worked with Cancer Research UK and the University of Cambridge to set up a Children’s Brain Tumour Centre of Excellence – to discover and develop new treatments to tackle brain tumours in children.

We’re pleased that similar collaborative arrangements are now being established to address the equally difficult challenge of curing brain tumours in adults.

ICR scientists have worked alongside other world-leading experts in the field, including clinicians and researchers from six countries, to establish what challenges need to be addressed to ensure more people with brain tumours survive the disease.

The expert panel, convened by Cancer Research UK, has produced a consensus paper highlighting the obstacles to progress that we need to overcome in brain cancer research and treatment. This paper has now been published in the journal Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology.

Meeting the brain cancer challenge

Led by Professor Richard Gilbertson, the Director of the Cancer Research UK Children’s Brain Tumour Centre of Excellence at the University of Cambridge and the ICR, the new position paper sets out seven key challenges that must be overcome in order to find new cures for brain cancers.

Many of these challenges are already the focus of research at the ICR and elsewhere, but the authors emphasise that there is much more work to be done – highlighting several areas for prioritisation.

Research at the ICR is underpinned by generous contributions from our supporters. Find out more about how you can contribute to our mission to make the discoveries to defeat cancer.

Bridging the gap

The first challenge is to redesign the research pipeline to make it more favourable to brain cancer research. In particular, the consensus statement criticises the disconnect between preclinical drug development and rigorous testing in the clinic.

Bridging this gap is something that the ICR has considerable expertise in.

Our research strategy, developed jointly with The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, spells out how we are applying our ‘bench-to-bedside’ approach to tackle cancer’s complexity and ability to adapt and evolve.

We are committed to opening up innovative new approaches to treatment, assessing these as quickly as we can in clinical trials, and working to embed new treatment approaches in routine healthcare.

We’re dedicated to applying this approach to all areas of our research, to ensure that our research has the greatest benefit to people living with cancer. And we believe our approach is very applicable to brain tumours.

Breaking down barriers

The second and third challenges laid out in the position paper encourage cancer researchers to use basic neuroscience research to its fullest, and to improve our understanding of the microenvironment around brain tumours.

The authors explain that while neuroscience research has given us a strong understanding of the cells, signalling pathways and blood vessels that exist in the brain in the absence of cancer, this is not translating into a better understanding of the conditions specific to brain cancer. Instead, the two fields seem to be relatively separate and need to be joined up more effectively.

More joint research into areas common to neuroscience and cancer – such as immune dysfunction, seen in both cancer and dementia – would help to drive brain cancer research forward.

This synergy could help researchers to discover and develop new treatments, including immunotherapies – an area which the ICR and the Royal Marsden are prioritising.

In fact, Professor Raj Chopra, Head of our Division of Cancer Therapeutics and one of the authors on the paper, is leading the ICR’s efforts to discover a new wave of immunotherapies.

Better modelling systems

The fourth challenge laid down in the consensus statement is for researchers to create new preclinical models of brain tumours. This is particularly important given the rarity of many brain cancers, and therefore the small number of patients who can take part in clinical trials.

The ICR is already leading the way in the development of new approaches to model cancers in the lab. Last year, research led by Dr Nicola Valeri showed that ‘mini-tumours’ – replica tumours grown in the lab from biopsy samples – could help to personalise treatments in a variety of digestive system cancers.

And Dr Rachael Natrajan has been using similar techniques to test how a breast tumour’s genetics affect its growth.

The next step will be to take this expertise and translate it into brain tumour research.

Challenge five is to improve our drugging of complex cancers. The authors encourage researchers to develop a better understanding of the biology of potential drug targets, and to use cutting-edge drug discovery approaches to find treatments that hit these targets – a strong area of focus for ICR.

A better understanding of the biology would also allow scientists to see how the disease adapts, evolves and progresses in response to treatment.

The ICR is again well positioned for this, as we discover more new cancer drugs than any other academic centre in the world. But if we are to rise to this challenge, we can’t – and won’t – rest on our laurels.

We are committed to identifying new drug targets, and to discovering innovative approaches to treatment, from adaptive, personalised targeted drug therapy to immunotherapy and precision radiotherapy.

And researchers in our Centre for Evolution and Cancer are finding ways to better understand cancer from an evolutionary perspective – including using a tumour’s genetic history to predict how it will change in future, and therefore to anticipate which approaches to treatment are likely to be most effective.

Improved classification

Putting precision medicine into action is the sixth challenge laid out by the authors. They recommend that we move away from a categorisation of brain tumours based purely on microscopic analysis, and instead incorporate genomic profiling into brain tumour classification.

Many of our researchers are already ahead of the game in this respect. Professor Richard Houlston, Head of our Division of Genetics and Epidemiology, has led major studies into the genetic causes of glioma, gaining unprecedented insights.

Professor Houlston’s team has discovered, for example, that different sets of genes influence a person’s risk of developing the two subtypes of glioma – glioblastoma and non-glioblastoma – showing that what we thought were closely related diseases are actually very different.

And recent research by Professor Chris Jones and colleagues has revealed that, based on their genetic profiles, childhood brain tumours can be divided into 10 different diseases – suggesting that each one should be diagnosed and treated based on its specific genetic faults.

The next step will be to integrate these approaches into clinical trials that allow for the development of precision medicine.

Tailoring treatments

The final challenge is to reduce the intensity and burden of treatment for some patients – in effect, balancing the likelihood of curing the disease with the side-effects of treatment.

While the previously discussed challenges are important for long term success, the authors suggest that this one could yield the greatest patient benefit in the immediate future, by reducing the risk of treatment-related side-effects, particularly in children.

Indeed, the ICR is already pioneering such a process in radiotherapy for breast and prostate cancers, with our research showing that a shorter course of treatment – with fewer, stronger doses – is as good as a longer course for treating the disease.

In the medium- to long-term, our ability to make real progress in the treatment of brain tumours will depend very much on making substantial progress in the other six challenges, including the integration of new and better data into diagnosis and treatment.

But the authors believe that this will be possible. The consensus paper gives the example of progress made with medullablastomas, where a breakthrough in understanding their biology led to a series of studies testing reduced doses of radiotherapy.

Call to action

While recognising that the seven challenges are ambitious, the authors of the expert report are optimistic for progress in the future.

They believe it is possible to achieve the changes needed to revolutionise brain tumour therapy, but also caution that it will require much greater coordination and investment, as well as a critical look at whether the approaches that underpin brain cancer research today are still fit for purpose.

The ICR will continue to lead the charge in taking innovative approaches to discovering and developing smarter, kinder treatments, and we hope that the publication of this paper will spur on others to join us and the brain tumour research community to achieve long term survival and eventual cures for adults and children with brain cancers.