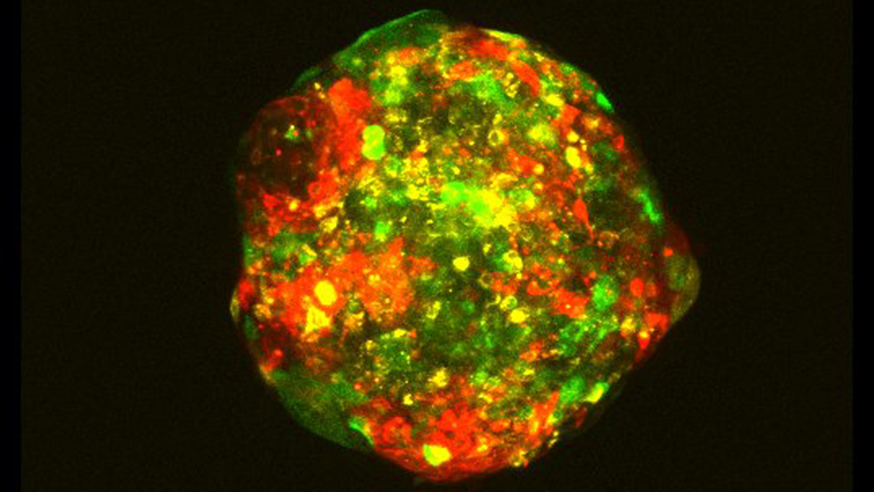

A multicellular 'spheroid' used by scientists to study cancer genes. This spheroid contains three distinct cell line clones from the MCF10 progression series. The three clones are stained with CellTracker dyes (red, green and yellow) and the image was taken with the Zeiss confocal (image: Barrie Peck)

A new technique to screen clumps of cancer cells in the lab which act like miniature tumours could help scientists discover potential new cancer drugs.

Scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, designed a new process to develop and test tumour ‘spheroids’ – three-dimensional clusters of cancer cells that mimic tumours in the body.

The researchers grew artificial mini breast cancer tumours and studied 200 genes frequently mutated in the disease to find drivers of tumour growth.

The process, which was published in the Journal of Visualized Experiments and funded by Breast Cancer Now, could be a cost-effective and more biologically relevant way to test genetic mechanisms in cancer than other methods.

Complex models

Cancer varies greatly from patient to patient, but most models used to find new treatments for the disease don’t reflect this complexity.

Treatments targeting specific genetic mutations in cancer are often discovered using cells grown on sheets of biological material. These are quick to produce but may fail to replicate the more complex conditions within a three-dimensional body.

For instance, two-dimensional models can’t replicate lack of oxygen and nutrients very well, and yet these can be key factors driving tumour growth.

Researchers at the ICR have for the first time developed a high-throughput technique to test the effect of inactivating specific genes on lab-grown ‘mini-tumours’.

Tumours screened

They used genetic screens of 200 common mutations in breast cancer and measured their impact on the mini-tumours after seven days.

They found silencing a number of genes linked to mutations that aid breast cancer survival, including HER2 and PIK3CA, reduced the size and viability of mini-tumours compared with control samples. Some of these effects were only seen in mini-tumours rather than cells grown in conventional 2D cultures.

Some mini-tumours displayed regions of low oxygen and tumour necrosis, which are common in aggressive cancer but difficult to recreate with other methods in the lab.

Dr Rachael Natrajan, Leader of the Functional Genomics Team at the ICR, said: “A lot of cancer research in the lab is done by growing cultures of cancer cells on flat plates, but these don’t replicate many of the features we see in tumours. We have developed a pipeline to reliably perform high-throughput assessment of novel cancer genes in tumour spheroids in the lab, and found that these mini-tumours can be used to test how genes affect cancer growth.”

Dr Barrie Peck, study co-lead and a Postdoctoral Training Fellow at the ICR, said: "Our technique is a halfway house between standard tissue culture and more complex in vivo techniques, and could help to identify new targets to treat cancer that you can't see in two-dimensional cultures."