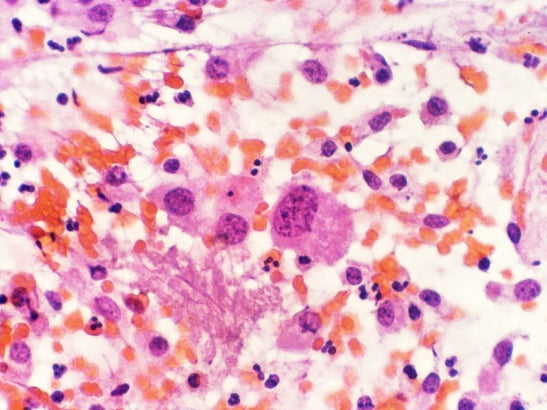

Myeloma of sphenoid sinus. (image: Wellcome Images/CC by-nc-nd 4.0)

Myeloma, also called multiple myeloma, is one of three main categories of blood cancer that affect white blood cells. The other types of blood cancer are leukaemias and lymphomas.

Myeloma is a cancer of the plasma cells. Plasma cells, along with other types of white blood cells, are produced by the bone marrow. White blood cells form a vital part of our immune system.

Our researchers are studying myeloma to understand more about how it develops. Research led by Dr Martin Kaiser, a Senior Clinical Research Fellow at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, is looking at the effect of switching genes on and off, and using this understanding to design and trial new treatments.

Dr Kaiser explains: “When myeloma develops, too many abnormal plasma cells are produced in the bone marrow. These myeloma cells can cause painful lesions and bone fractures, and produce antibodies that can harm the kidneys.

“At the same time, the body produces fewer of the other types of white blood cell, meaning people with myeloma can get severe infections out of the blue.”

In your genes

When viewed through a microscope all myeloma cells look alike. But at the genetic level, myeloma cells are highly variable.

Our researchers, including Dr Kaiser, have played leading roles in demonstrating the genetic variability in myeloma cells. They are also using this knowledge to test treatments in large-scale clinical trials. These trials have helped to establish the best treatments for myeloma, including the use of a drug called lenalidomide in patients who still have the disease after initial treatment. The success of lenalidomide in the trials has led to related drugs like pomalidomide also being developed as treatments for myeloma.

Recent trial results have shown that 90% of patients with the worst prognoses can be identified using a test for mutations in nine key genes. Researchers are now examining how to use this ability to spot those at highest risk to plan treatments that extend life more effectively – as well as delving into more complex questions, such as how genes are switched on or off in myeloma.

Vital insights

We are also examining myeloma from different angles. Dr Nandita deSouza’s group has established whole-body scans using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a tool to help doctors diagnose how far the disease has spread in individual patients. Their research will free doctors from having to rely on repeat X-rays of individual bones or repeat bone marrow biopsies, which are less precise and can be painful.

And Professor Richard Houlston’s team – who are experts in large-scale population studies of genetics – has made several important discoveries about the fundamental causes of myeloma. His team has found 17 genetic variants – slight changes to the DNA sequence – that seem to put a person at higher risk of developing myeloma.

In 2016, they made two new findings. They discovered that one genetic variant helps to increase the production of a protein that raises the risk of myeloma, and they found that the gene that produces osteoprogesterin – usually associated with regulating bone density – could be involved in causing bone disease in patients with myeloma.

Our research programme in myeloma is allowing us to identify which patients are most at risk, and which treatments are most likely to help them. Not only are our studies providing new clues that could lead to completely new treatments in the future but, importantly, we are providing new tests and clinical tools that clinicians can use right now to maximise the benefits that patients get from current treatments.

This article first appeared in our supporter magazine, Search. You can sign up to receive Search directly to your inbox.