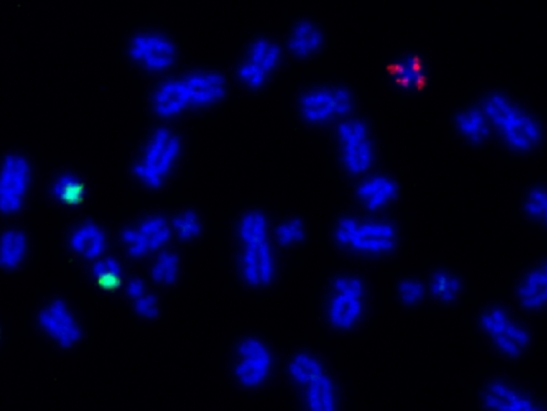

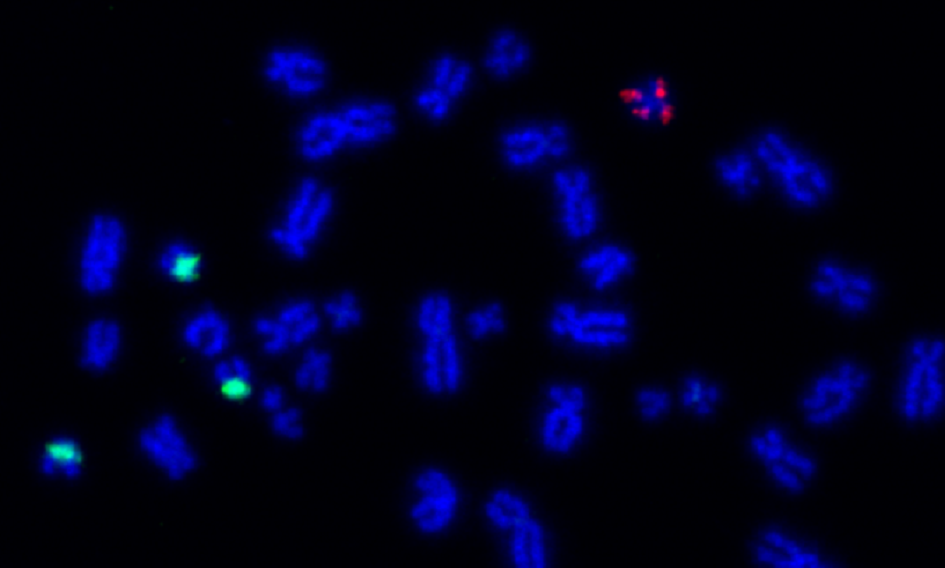

Image: Fluorescent chromosomes in BRG1 knockout cells. Credit: Professor Jessica Downs.

Scientists have found a genetic mutation that results in cancer cells being able to tolerate having an abnormal number of chromosomes – a condition which normally kills cells – allowing them to adapt to their environment and continue to grow.

Human cells usually have 46 chromosomes (23 pairs). If they have more or fewer, a state called aneuploidy, then they are likely to die or grow very slowly. However, aneuploidy is very common in growing cancers.

The study, led by scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, showed that when they switched off the gene for a protein called BRG1 cancer cells were able to gain extra chromosomes without any of the negative results normally seen in aneuploid cells.

The researchers say this new study on cancer cells in the laboratory provides insight into why so many cancer cells are aneuploid and yet are still able to undergo excessive growth. They hope these findings will add to our understanding of how cancers are able to rapidly evolve in new environments.

Discovery science, like this work, is vital for cancer research as it increases our fundamental understanding of cancer biology. Without findings which illuminate what is going on within cancers it would be impossible to know where to start when looking for new drugs that might be effective against the disease.

The study is published in Nature Communications and was funded by Cancer Research UK and the Medical Research Council.

The role of the BRG1 gene

The researchers looked at what happened when they turned off the gene for BRG1 in cancer cells. They found that to start with the cells were unhappy and replicated very slowly. But gradually over eight months they recovered.

This steady return to fitness was associated with many of the cells becoming aneuploid, something not seen in the control cells where the BRG1 gene was active. These findings suggest that the loss of BRG1 allows the evolution of aneuploidy in cancer cells.

Being aneuploid may be advantageous to cancer cells as it provides more genetic variation and additional copies of genes which allows them to evolve and adapt to new environments. Understanding and confronting cancer’s ability to adapt and evolve is a key area of research at the ICR and forms a central part of the ICR’s current research strategy.

This research also highlights the role of a protein complex called SWI/SNF, a group of proteins that work together to wind and unwind DNA so it can be copied or repaired.

One in five of all human cancers contain a mutation which causes a loss of function to the SWI/SNF complex, suggesting SWI/SNF works as a tumour suppressor. However, we are far from fully understanding the role of SWI/SNF in cancer.

BRG1, the protein turned off in this study, forms a key part of the SWI/SNF complex. As cancer cells with aneuploidy can happily exist when they have lost BRG1, this research suggests that SWI/SNF has a role to play in preventing the toleration of aneuploidy.

Surviving with a different number of chromosomes

The researchers additionally saw that the biological pathways linked to aneuploidy tolerance changed immediately when BRG1 was lost. The scientists suggest that these early changes in aneuploidy-tolerance pathways allow the cells without BRG1 to have different numbers of chromosomes without the usual loss of health seen in aneuploid cells.

The scientists further tested the role of BRG1 in aneuploidy tolerance by inducing aneuploidy in cancer cells which had BRG1 turned off and in control cells with active BRG1.

They found that the number of cells without BRG1 that survived after seven days of exposure to a drug which causes aneuploidy was approximately double the number of cells with BRG1 that survived. This provides further support to the idea that cells without BRG1 are better at tolerating aneuploidy than those with the protein.

Providing clues

Study lead Professor Jessica Downs, Professor of Epigenetics and Genome Stability at the ICR, said:

“Our research has helped to uncover one factor that could explain how many cancer cells are able to happily exist and grow with an abnormal number of chromosomes when this state normally results in decreased cell fitness. In the future these finding might provide clues as to how cancer growth may be disrupted.

“The work we do to understand the basic biology and evolution of cancers is crucial in our fight against this disease.”

Joint first author of the study Dr Pedro Zuazua-Villar, Senior Scientific Officer in the Epigenetics and Genome Stability Team at the ICR, said:

“Cancer is so challenging to treat because it is enormously complex, and it can adapt to changes in its environment. This study finds that being tolerant to aneuploidy is one way that cancer cells are able to adapt and evolve so effectively.

Through studies like this we hope to ultimately be able to predict the path of cancer evolution from a single tumour sample, so doctors can see and counter-act cancer’s next move.”