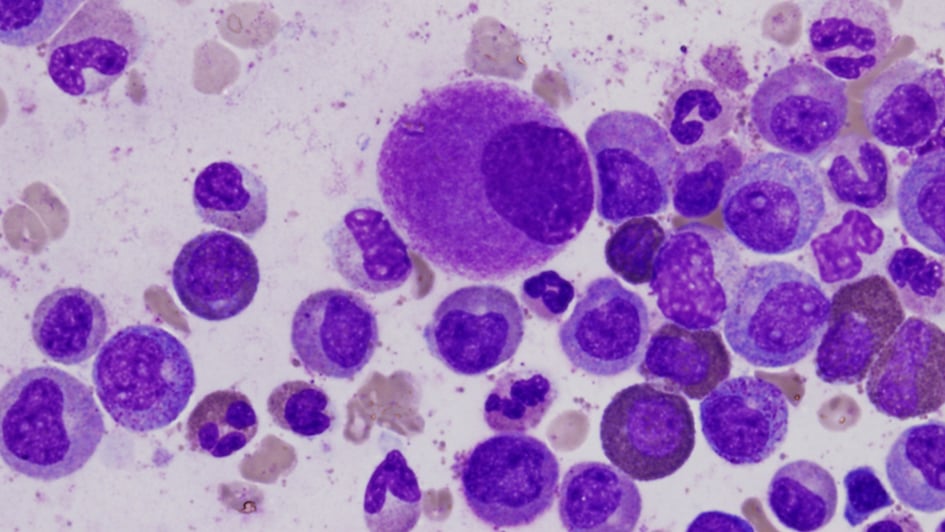

Image: deformed cells in the bone marrow, typical of leukaemia

Leukaemic cancer cells can ‘go to sleep’ and thus avoid the effects of chemotherapy, sometimes for years. It turns out that whether the cell is in this dormant state or not increases its chances of surviving chemotherapy and is completely independent from its mutations, as previously assumed.

The discovery, made by a collaboration between researchers at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and University College London (UCL), could help direct research towards new, more effective treatments for childhood leukaemia that stop cancer from coming back. For example, testing for dormant cells to decide whether to continue therapy, or using a hormone to activate dormant cells and catch them in a vulnerable state.

Cancer cells have some common traits with healthy stem cells in the body. They both go in and out of dormant states as part of their natural cycle. When dormant, these cells avoid environmental stress, such as chemotherapy.

Dormant cells are in a hibernation state, neither affecting the body but also unaffected by drugs that would normally destroy them. They pull off this trick with the use of fast-acting pumps that eject any foreign drugs or toxins that enter the cell.

This breakthrough research, published in Nature Cancer, suggests an answer for the long standing conundrum as to why leukaemia patients need two to three years of maintenance therapy after their initial treatment.

Doctors must wait for the possibility that dormant cancer cells wake up with the hopes of catching them quickly with chemotherapy. This is to lower the chances of re-establishing a large population of malignant cells.

Which cells survive chemotherapy?

The ICR component of the study, which was largely funded by the Wellcome trust and Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation, took samples of leukaemia cells before treatment from five patients with childhood leukaemia.

Childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (BCP-ALL) is a rare blood cancer. It creates too many immature white blood cells in the blood and bone marrow.

Chemotherapy reduces the number of cancerous cells in the blood but some cells are able to survive. Knowing the profile of the surviving cells is essential for creating more targeted treatments.

We are an internationally leading research centre in the study of cancers in children, teenagers and young adults.

Before the chemotherapy, the team physically sorted rare individual cells from the patients that had markers of dormancy. They then profiled these rare cells for mutations and compared them with a mutation profile family tree made from the original sample.

Their findings were that, on specific branches of the family tree that arose from mutations, the dormant cells existed throughout the entire family tree.

They concluded that mutational features and genetics could not determine whether a cancer cell would be in a dormant state at the time that chemotherapy is introduced.

Professor Sir Mel Greaves, founding director of the Centre for Evolution and Cancer at the ICR and Professor of Cell Biology who led the ICR team working on this research, said:

“They are probably flipping in and out of dormancy all the time. The ‘fortunate’ minority cells that happen to be dormant at the time of chemotherapy are the ones that survive.”

Sleeping through treatment

The team at UCL, led by Professor Tariq Enver who was previously a scientist at the ICR, obtained parallel results from tests on cells that survived chemotherapy. His team implanted human leukaemic cells in mice and then gave them chemotherapy that is similar to what patients receive.

Dr Virginia Turati, a postdoctoral researcher at UCL who led the laboratory experimental work, said:

“We observed, strikingly, that all of the different genetics before treatment were present after treatment. So, there was no selection based on genes. We asked ourselves ‘What is going on?’

“We observed that chemotherapy was selecting a very specific cell state. They were very much dormant according to the markers that we have for that cellular state. Since chemotherapy targets cells that are very active these cells could survive by sleeping through treatment.”

Childhood leukaemia, like BCP-ALL, has to be treated for two or three years. First, there is an induction dose of chemotherapy followed by a longer-term maintenance period of therapy.

Influence treatment for BCP-ALL

The next stage is to consider how this finding might influence treatment for BCP-ALL.

Professor Greaves suggested that clinics could use sensitive tests for dormant leukemic cells in blood at the end point of maintenance therapy. If there are still dormant cancer cells present, then the doctors know that the maintenance therapy needs to continue.

Another suggestion looks at the opposite and perhaps counterintuitive approach. Instead of waiting, administer a hormone to activate all of the dormant cancer cells.

“In trying to activate the dormant cells and force them back into the cell cycle, the plan would be to then administer more chemo and whack them all in one go,” said Professor Greaves.

This method is potentially more risky as the activation needs to be limited to cancerous cells and not healthy cells.

Dr Turati also noted: “Adult leukaemia treatment also relies on chemotherapy to target cancer cells that cycle through active and dormant states. Although adult leukaemia has differences to childhood leukaemia, it would be worth investigating this same type of treatment.”

.

.

.

.