Evolution is change over time, and it is well-accepted that cancers evolve through the stepwise accumulation of somatic mutations. Logically, mutations ‘cause’ cancer, and therefore, simplistically, the key to preventing cancer could be to avoid mutations. However, epithelium, like the skin and intestines, divide and shed millions of cells every day, and could accumulate many mutations because DNA replication is imperfect.

One potential safeguard against ‘replication’ errors is a stem cell hierarchy, where long-lived stem cells divide infrequently. However, studies in mice indicate that both skin1 and intestinal stem cells2 are not quiescent but rather are actively dividing. Such tissues are primed for evolution because many more cells are produced than can survive.

One direct way to determine whether normal cells accumulate mutations is to sequence their genomes. Detecting mutations in normal tissues is difficult because they are polyclonal. Each normal cell could have thousands of mutations, but because they differ between cells, the frequencies of specific mutations are too low to detect by conventional DNA sequencing. By sequencing individual subclones, either by subdividing normal skin into very small portions3 or by culturing individual intestinal crypt subclones4, new studies indicate that normal somatic cell genomes mutate almost as fast as cancer cell genomes (Table 1).

Table 1: Mutations in normal and tumour tissues

| Tissue | Mutations per Mb | Mutation Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | ~2-6* | UV light | 3 |

| Skin squamous cell carcinoma | ~1 to >50 | UV light | 3 |

| Colon | ~0.8** | Replication errors | 4 |

| SI | ~0.8** | Replication errors | 4 |

| Colorectal (MSI-) | ~1-5 | Replication errors | 13 |

* average age of 63 years

** at age 70 years

In skin the dominant mutation signature is caused by ultraviolet light, and in the intestines it appears to be aging or replication errors that result in the mutation signature. Hence, normal and cancer cell lineages appear to acquire most of their mutations by the same processes (Table 1). Of particular interest are comparisons between the small intestines and the colon4because colorectal cancer is very common and small intestine cancer is about 100 times less common even though the small intestine is longer (30 feet versus 6 feet for the colon); in mice, both colon and small intestine stem cells are mitotic2. Their microenvironments are strikingly different, with the small intestine virtually sterile and the colon filled with a rich microbiome. Yet there were no appreciable differences in mutation frequencies or spectra between the small intestine and the colon (Table 1). Mutations cause cancer, but the small intestine somehow manages to avoid cancer despite accumulating the same number of replication errors as the colon. What might be going on?

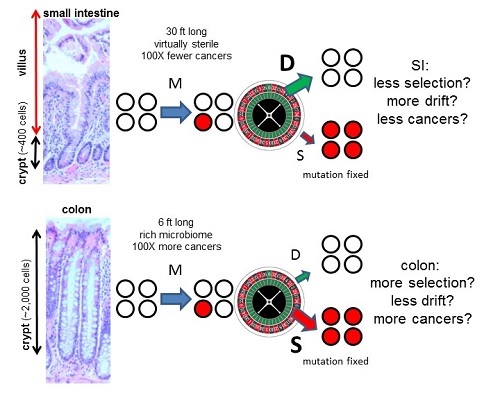

Evolution is not just propelled by mutation because two other major evolutionary forces (drift and selection) determine whether or not a cell survives. Intestinal crypts have a highly localised micro-environmental region which regulates cellular dynamics. They contain multiple stem cells that normally divide and turn over by a niche mechanism (Figure 1). A key point is that every new mutation has a period of uncertainty because its fate depends on the fate of its stem cell lineage – every new stem cell mutation is eventually lost or forever fixed (present in all crypt cells). For example, a neutral or passenger mutation is randomly fixed or lost through drift. Most new mutations are lost because the odds of random fixation are 1/N (N = stem cell population size).

Figure 1: Interactions of the three major parameters of evolution (mutation (M), drift (D), and selection (S)) within intestinal crypt stem cell niches. Crypts contain small numbers of mitotic stem cells at their bases that produce differentiated progeny that migrate upwards and die. Stem cells may divide asymmetrically or symmetrically, and eventually all present-day stem cell lineages are lost except one. Therefore, most new mutations are lost and a minority of mutations are fixed. Colon crypts are larger than SI crypts. Because selection is less efficient in smaller populations7, relatively fewer driver mutations may accumulate in the SI than the colon (this concept is explained in a YouTube video). Hence, intrinsic tissue architectural difference may account for why colon and SI stem cells acquire similar numbers of mutations with aging, but colon cancer is common and SI cancer is rare. The size scale is the same for the colon and SI images.

By contrast, most driver mutations could be fixed whenever they arise if they confer a selective survival advantage over neighbouring crypt stem cells. Such preferential fixation of driver mutations would increase the risks for progression to cancer. But what if it were possible to minimise selection and maximise drift? In this case, driver mutations would be fixed no more often thanpassenger mutations, which would reduce cancer risks and could potentially explain how the small intestine can accumulate similar numbers of mutations as the colon but have significantly lower cancer risks (Figure 1).

It is commonly assumed that selection overwhelms drift. However, selection and drift depend on interactions between neighbouring cells, and small intestine and colon crypt neighbourhoods differ. An architectural difference is that small intestine crypts are smaller than colon crypts (~400 versus ~2,000 cells). Population genetics theory indicates that selection efficiency depends on the numbers of competing individuals7. Selection is efficient in large populations, but as populations diminish in size, drift become increasingly more important than selection in determining survival. It may be possible to exploit ‘randomness’ as an anti-cancer mechanism because in very small stem cell populations there may be less preferential fixation of drivers. Experimentally, sporadic stem cell mutations in even canonical drivers (Apc, Kras, Tp53) are frequently lost from crypts8. If small intestine crypt stem cell populations are smaller than in the colon, drift will be stronger (Figure 1), thereby reducing driver mutation accumulation and cancer risks even though net mutation accumulation is unchanged.

Mitotic stem cells and random replication errors provide a mechanism where age or total numbers of stem cell divisions (‘bad luck’9) correlates with increased cancer risks. Mutations per se do not cause cancer, but the likelihood of one cell accumulating the right combination of driver mutations increases with the large number of mutations that normally accumulate with ageing. However, the two other forces of evolution (selection and drift) add an element of ‘skill’ such that the same numbers of mutations in the small intestine lead to far fewer cancers than in the colon. For this strategy to work, bona fide driver mutations must be exceedingly rare, which seems likely because colorectal cancer is still very rare relative to all the mutations that accumulate in normal crypts. Evidence to support a greater role of drift in protecting the small intestine from cancer would be higher frequencies of deleterious mutations and lower frequencies of driver mutations. Although one cannot convert a colon into a small intestine, stem cell numbers per crypt could be altered because stemness depends on signalling from the surrounding mesenchymal niche10. Environmental manipulations that reduce cancer risks could work by minimising stem cell niche sizes.

Most of us have ~100 protein truncating germline mutations11, illustrating that mammalian genomes are robust to variation, rationalising why so many somatic mutations can accumulate throughout life without visible evolution. Mutations cause cancer, but the vast majority of mutations do not change the phenotype. The neutrality or near neutrality of most mutations can help explain why many colorectal tumours, despite extensive number of subclonal mutations, appear to be single ‘Big Bang’ expansions12. Evolution entails competition between neighbouring cells, and the exact subdivision of cells into small replicative units may be an elementary reason for why certain tissues are more tumour prone. Although mutations may be inevitable with ageing, the small intestine can provide mechanistic hints of ways the other major forces of evolution (drift and selection) are manipulated to prevent cancers.

References

- Clayton E, Doupé DP, Klein AM, Winton DJ, Simons BD, Jones PH (2007) A single type of progenitor cell maintains normal epidermis. Nature. 446:185-9.

- Barker N, et al (2007) Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449:1003-1007.

- Martincorena I, Roshan A, Gerstung M, Ellis P, Van Loo P, McLaren S, Wedge DC, Fullam A, Alexandrov LB, Tubio JM, Stebbings L (2015) High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science 348:880-6.

- Blokzijl F, de Ligt J, Jager M, et al (2016) Tissue-specific mutation accumulation in human adult stem cells during life. Nature 538:260-264.

- Lopez-Garcia C, Klein AM, Simons BD, & Winton DJ (2010) Intestinal stem cell replacement follows a pattern of neutral drift. Science 330:822-825.

- Snippert HJ, et al (2010) Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143:134-144.

- Whitlock MC (2000) Fixation of new alleles and the extinction of small populations: drift load, beneficial alleles, and sexual selection. Evolution; international journal of organic evolution 546:1855-1861.

- Vermeulen L, et al (2013) Defining stem cell dynamics in models of intestinal tumor initiation. Science 342:995-998.

- Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B (2015) Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 347:78-81.

- Clevers H, Loh KM, Nusse R (2014) Stem cell signaling. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science 346:1248012.

- Lek M, et al (2016) Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536:285-91.

- Sottoriva A, Kang H, Ma Z, Graham TA, Salomon MP, Zhao J, Marjoram P, Siegmund K, Press MF, Shibata D, Curtis C (2015) A Big Bang model of human colorectal tumor growth. Nat Genet. 47:209-16.