Image: Dr Matthew Clarke pictured outside the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Collaboration is an essential contributor to the success of any form of research. My PhD project focussed on a very rare group of brain tumours (infant high-grade gliomas) and so collaboration with both national and international collaborators was vital to ensure samples were available for inclusion and further study. As a result of this work, there were nearly 120 different authors listed as part of the publication.

Some of these crucial collaborators were based at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Professor David Ellison, an internationally renowned neuropathologist, had provided several cases and his expertise as part of my study. After my PhD concluded, we kept in touch, and he very kindly invited me to come and visit St. Jude. I jumped at the opportunity both to visit the hospital and to learn from someone I have always admired and respected.

After navigating the Covid-19 testing requirements for the US, I successfully arrived, and my adventure began! I was provided with a lovely apartment just across from the Mississippi River which offered some incredible sunsets and lovely walks on my way back from the hospital.

The unusual origins of St. Jude

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital was founded in 1962 by the entertainer Danny Thomas. He had been struggling for work in this industry which led him to say a prayer to the patron saint of lost causes, St Jude Thaddeus: “Show me my way in life, and I will build you a shrine.”

Shortly after this, Danny’s fortunes turned around and he enjoyed a very successful career during which he received a series of awards. True to his word, Danny decided to embark on the development of the hospital and chose to do so in Memphis, one of the most deprived cities in the US. At the time of the hospital’s founding, the US was in the midst of a very divisive period associated with the civil rights movement.

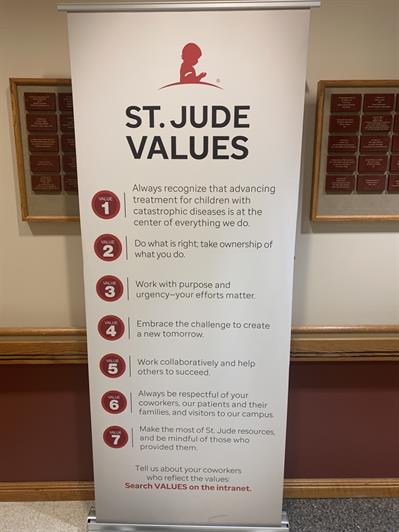

But the hospital challenged this division and, through its mission statement, it aimed to advance cures, and means of prevention, for catastrophic paediatric diseases through research and treatment. Also, no child was to be denied treatment based on race, religion, or a family's ability to pay.

Image: St. Jude's values on display for staff to see.

To further cement the inclusivity, segregation was not seen in the hospital, and the architect was an African American called Paul Williams. It was certainly a place leading the way for change both in terms of the social, scientific, and medical spheres.

Danny and his wife are buried on the hospital site, and a memorial garden and building have been developed to describe the history of the hospital for visitors to wander around. It is also the site of the annual graduation ball that the hospital school hosts for the children – there is even a red carpet for them! Danny Thomas’ children are still involved with the hospital to this day.

Funding

Much like the UK, healthcare in the US has many challenges in terms of provision, access, and availability. Affordability is also a particular issue in the US, with many people unable to afford health insurance, who can then face huge bills for the cost of their care.

An impressive and admirable aspect of St. Jude is that the patients and their families do not receive a single bill for their treatment; they also do not pay for travel, accommodation, or food whilst they are staying there. They assist patients and their families to travel across the US (and the world) to receive the care they need.

While I was there, I heard about a consultant who had helped some Ukrainian families to travel to St. Jude to receive the treatment they needed. So how do they manage to fund this alongside the research that they do?

The ‘ALSAC’ organisation is dedicated to the fundraising and financial provision of the hospital. They host specific fundraising events and develop videos, adverts and other resources to help raise money. This hard work helps to provide significant donations from a vast number of individuals and companies that work closely with the hospital.

But most of the funding actually comes from US families donating just $25. Even during the pandemic, the funding did not drop. This allows the hospital to function at a level that allows it to be at the cutting-edge of both treatment and research. There is a saying in the medical profession in the US – “If not at St. Jude, where?”

The pathology department

As a trainee neuropathologist and pathology enthusiast, I was eager to explore the pathology department at St. Jude. It was a very impressive department; the team of consultants were all involved in research at the hospital to varying degrees. The extent of molecular investigations was also very impressive, with the provision of a laboratory that was dedicated to sourcing and testing previously unused investigative and diagnostic tests at the hospital.

The use of sequencing was kept very broad, using whole genome sequencing and RNA sequencing frequently, rather than targeted panels. This provides valuable data that can be fed into the research teams who are working alongside them. The neuropathology team consisted of four consultants, all of which took an interest in a particular area of brain tumour research including gliomas, ependymomas or embryonal tumours.

They provided a vast set of cases that I was able to work through, with the help of their expert tuition. They also showed me some very interesting current cases where the diagnosis was not apparent. It was very valuable for me to see the approach used by them to find the answer. I was also able to see examples of cases with the words: “you may not ever see this in your career again.”

They are a referral centre and so are asked for second opinions about a variety of different brain tumours, which provides such a valuable training opportunity for junior neuropathologists and other pathology trainees. It was also impressive to see the other specialties of pathology integrated into the department; microbiologists, veterinary pathologists, cellular pathologists, and neuropathologists were all considered to be part of the same team, working alongside each other. Integration was a key approach on display in the department and this also extended into their research work.

Integrated research

Research is integrated into the very fabric of the hospital institution. The teams are always looking for opportunities to use the data to discover new things about disease and treatment. This begins at the time of biopsy; I spoke with one of the neuropathologists who told me that in theatre, material from a brain tumour resection can be provisioned for research and well as diagnostics.

For example, two cores are used for histological diagnosis, two are frozen for molecular testing, two are used to establish a patient-derived cell culture and two are used for single-cell RNA sequencing. These results can then be filtered through and influence the patient’s treatment in real time.

The consultants are also involved in different streams of research in specialist areas and there is encouragement and support to allow them to develop their skills and proposals further. Integrated roles featuring both clinical and academic time are a very frequent occurrence at St. Jude and are actively encouraged; it is no doubt one of the contributing factors to the success.

Global engagement

There is also a strong collaborative ethos with data made publicly available wherever possible so that other researchers from around the world can utilise it. There is also continued onsite development of the research facilities and resources; they have recently opened a new ‘Inspiration 4’ building providing additional research space for research teams to expand their vital work.

There is also a strong collaborative ethos with data made publicly available wherever possible so that other researchers from around the world can utilise it. There is also continued onsite development of the research facilities and resources; they have recently opened a new ‘Inspiration 4’ building providing additional research space for research teams to expand their vital work.

St. Jude is also keen to ensure equality of access to treatments and good practice for patients and clinicians around the world. They run a global outreach programme, helping to provision the implementation of molecular testing for lower-middle income countries and other centres both in the US and around the world.

This policy of shared learning is inspiring and helps to ensure that patients all over the world can receive the optimal diagnostic work-up and quality of care.

Image: The many flags representing the diverse workforce at St. Jude.

Wellbeing and diversity

St. Jude show that they value the wellbeing of all who set foot in the hospital, and it is clear to see from the interactions with staff. Everyone was so welcoming and supportive. As you walk into the Danny Thomas Research Tower and look up, you can see many different flags representing the diversity of international staff that are employed there. And, speaking of hospital employees, there are three unique members of staff; three golden retrievers who are wellbeing officers of the hospital!

Two are dedicated to the patients, but one is for the staff, and I was lucky to meet Rosalie on my first day! If you are having a challenging day, you can put in a request for a visit and Rosalie and her handler will come and say hello and provide the opportunity for some canine comfort.

As shown by the mission statement, the hospital is devoted to ensuring equality and inclusion for all and publish a yearly report to illustrate their ongoing engagement with this, both in terms of staff and patient populations. It creates a very safe, open and welcoming environment for all.

They also try to support the continued education of the patients while they are staying in the hospital; I was lucky to be shown the onsite school where children of different ages can be provided with a variety of educational opportunities to help them alongside their ongoing treatment.

Image: Matt meets one of the wellbeing dogs, a Golden Retriever called Rosalie.

My reflections

The time I spent at St. Jude was very inspiring. Not only did I learn a huge amount of neuropathology from some of the experts in the field, but I got to see further examples of the significant difference research can make to the outcomes of patients.

Much like the relationship between the ICR and The Royal Marsden, research is integrated into patient care and the diagnostic workflows of St. Jude, which allows cutting-edge developments and discoveries across the different disease spectra.

This helps both to ensure the right targeted treatments are given to children but also supports the development of new ones. There have been significant breakthroughs in paediatric brain tumour research from both organisations, but there remains much to discover and understand.

The visit highlighted for me how crucially important engaging and training the next generation of scientists and pathologists is to continue this proactive approach, and I continue to be extremely grateful to have had the opportunity to undertake my PhD and continued research training as part of the Glioma Team led by Professor Chris Jones.

Collaboration is key and we can learn a lot from each other and different institutions. Both organisations also work to ensure that the impact of the research undertaken is felt by patients across the global stage, helping to reduce health inequalities.

The open and collaborative nature of St. Jude and its proactive approach to training also mirrors its approach to diversity and inclusion for both patients and staff; this fosters a working environment that welcomes all and allows progress to be made, principles shared with the ICR and The Royal Marsden.

The funding opportunities provided to the hospital are vital to its work, but also highlights how vital investment is for research to continue at pace. I will always treasure fond memories of my time spent there.