Science Writing Prize 2024 - Designer cellular therapies for solid cancers: Science fiction or reality?

When I first started as a research fellow in a laboratory producing designer anti-cancer immune cells, my initial thought was that it was more akin to science fiction than the National Health Service. The process, however, did make sense on paper; take ineffective immune cells from the blood of patients with active cancers, genetically modify in a laboratory to target towards the patient’s tumour, activate and expand up to numbers in the order of billions, then administer them back to the patient; all in an attempt to ‘reprogramme’ anti-cancer immunity.

The levels of complexity to this process (known in the field as Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cell therapy or CAR T) soon became apparent. Human T-cells are delicate beings when living outside of their host. Days were often spent nurturing petri dishes of T cell’s, feeding and caring for them, protecting from frequent bacterial infestations. If successful, the survivors were then left to mix with pre-prepared man-made viruses. These have the capacity to infect and insert custom DNA into T cells, in such a way as to change how that cell behaves.

The resultant synthetic cells then have a newfound anti-cancer ‘killing’ power which could be put to the test in the laboratory. In one dish were cancer cells mixed left to rest with unmodified T cells, in the other, cancer cells with the new, modified cells. Looking down the microscope the results were astounding. The designer T cells could be seen eradicating the cancer cells within a matter of days, whilst the natural cells simply lay dormant.

Whilst this process is a sight to behold in the controlled environment of a squeaky-clean laboratory, the success of CAR T in solid tumour oncology has been very limited. The complexities of the tumour’s habitat, or microenvironment (TME), are vast, meaning that CAR T cells seldom make it past the biological roadblocks en route to the tumour.

Such scientific realisation has led to enthusiasm in a simpler approach to solid tumour cellular therapy. An idea first devised by a team at the National Institute of Health (NIH) in Maryland, USA, in the 1980’s has recently been re-adopted by the field. Tumour infiltrating lymphocyte therapy (TIL) relies on the basic theory that immune cells that have made it into a growing tumour have already done most of the hard work. With this in mind, the process involves surgically removing the most accessible tumour site and physically extracting T cells from within. These are then carefully nurtured and expanded, as is done for CAR T, however no further modification is required. When re-infused into the patient, dramatic responses have been seen, notably in patients with advanced skin cancer (melanoma) who have exhausted multiple lines of previous immunotherapy. This advance has heralded the first FDA approval for a solid tumour cellular therapy. Lifileucel, a TIL product developed by Iovance biotherapeutics, is now in use in the USA for patients with advanced melanoma. With a hefty price tag, it is yet to be seen whether it will be adopted by European health authorities, but such decisions are expected in 2025.

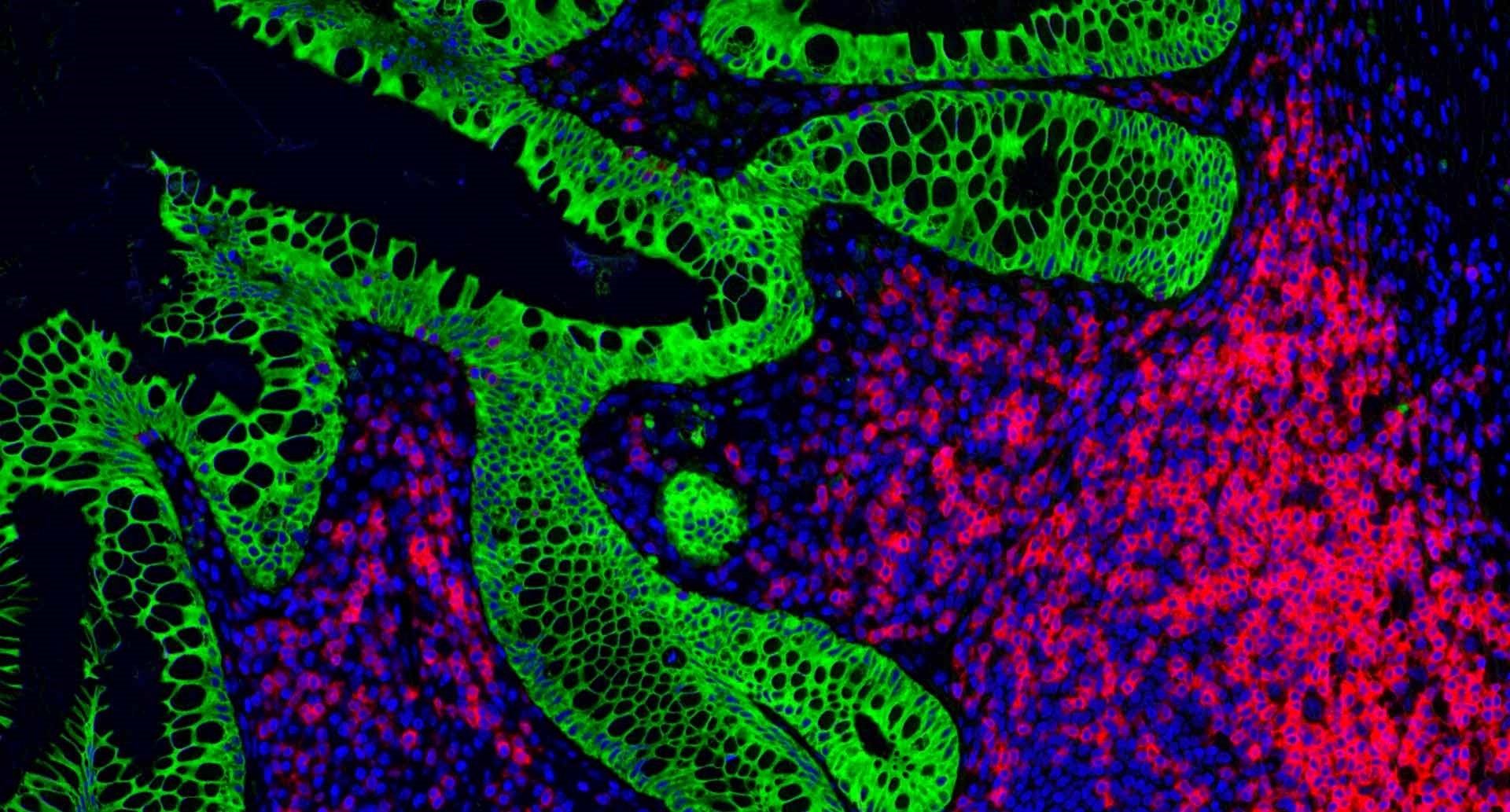

The problem is that TIL therapy still doesn’t work for everyone. In fact, only around 35% of patients with advanced, pretreated melanoma respond. Therefore, my current work is investigating reasons for these differing responses. I am particularly interested in a relatively poorly understood population of cells called granulocytes. These bystander cells can be seen in diverse groups and numbers and were previously not thought to impact immunotherapy efficacy. Now we know they play a key role in anti-cancer immunity, and it is likely that a new wave of treatments will be targeting their molecular pathways.

So, what does the future look like for solid tumour cellular therapy? As science rapidly advances, the complexity of designer CAR T cells is exploding. 4th generation CAR T cells armoured with molecular payloads, internal DNA switches that can be turned off by infusing additional drugs, the list goes on. But is the issue that we are modifying biology that we do not fully understand? Of the hundreds of CAR T studies that have been tested in solid cancers, very few have shown any tangible results in patients. Instead, most of the recent progress has been made by the simpler and less synthetic TIL therapy. In the coming years it will be fascinating to see how the interface between complex designer T cells and patient outcome develops, where I for one hope that these exciting and novel technologies can ultimately lead the way in the global fight against cancer.

This piece was highly commended in the Mel Greaves Science Writing Prize.

Dr Max Julve is an ST6 registrar in medical oncology at the Royal Marsden Hospital. He is currently writing up his MD(res) thesis investigating the role of immunosuppressive granulocytes in cancer immunotherapies, completed at the ICR.

He has a specialist interest in solid tumour cell therapy and has recently undertaken a three-year clinical research fellowship in this field with the team of Dr Andrew Furness at the Royal Marsden.

Additionally, Max completed an NIHR academic clinical fellowship at Imperial College London, with previous experience engineering CAR-T cell therapies for transcriptional optimisation.