What is blood cancer?

Blood cancer is an umbrella term for cancers affecting the blood, bone marrow or lymphatic system. Despite being a common cancer that can affect people of any age, it is often not very well understood. Here, we answer some of the most common questions people ask about this disease.

What are the main types of blood cancer?

There are more than 100 different blood cancers, most of which fall under one of three main types: leukaemia, lymphoma and myeloma.

Leukaemia (‘leuk’ meaning white and ‘aemia’ referring to a condition of the blood)

Leukaemia occurs when there is abnormal cell growth in the bone marrow cells. If the affected marrow cells mature into lymphocytes – a type of white blood cell – a person has lymphocytic leukaemia. However, if they become red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets, the disease is called myelogenous leukaemia. Either way, the mutated cells enter the bloodstream, where they crowd out healthy blood cells.

Both subtypes can be further categorised as either acute or chronic. Acute leukaemia progresses quickly and aggressively, whereas chronic leukaemia develops very slowly.

Lymphoma (‘lymph’ referring to lymphocyte and ‘oma’ derived from the Greek word for tumour)

Lymphoma also affects lymphocytes, but it originates in the lymph nodes or spleen, and the abnormal cells enter the clear fluid called lymph that flows through the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system has several roles, including managing fluid levels and protecting the body from infection.

The two main types of lymphoma are Hodgkin lymphoma, which is most common in people aged 15 to 40, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which typically affects people over the age of 60. Doctors can distinguish between the two by looking for specific lymphocytes called Reed-Sternberg cells. These distinctive, large cells, which can contain more than one nucleus, are only found in people with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Myeloma (‘myelo’ and ‘oma’ derived from the Greek words for marrow and tumour)

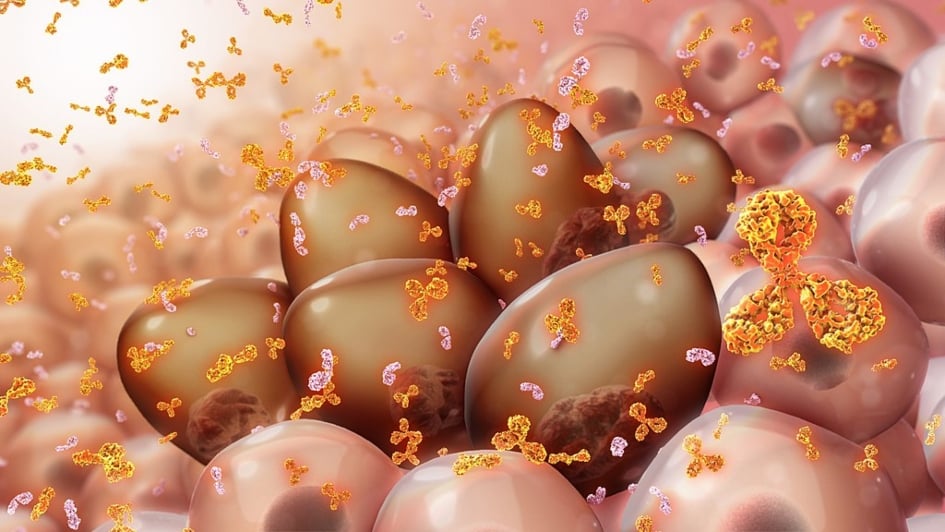

Myeloma, which people sometimes refer to as multiple myeloma, forms in plasma cells in the bone marrow. These cells develop from B cells, also called B lymphocytes, which are white blood cells that make antibodies. Antibodies are designed to destroy a specific pathogen – most often a virus, bacteria, fungus or parasite – and a plasma cell can release thousands of them every second.

Myeloma cells still secrete antibodies, but they are abnormal and not able to fight pathogens effectively.

There are many subtypes of myeloma, but they can all be categorised as either active or smouldering. People with active myeloma will experience symptoms and require prompt treatment, but those with smouldering myeloma will not need treatment for a while, if ever. The disease is asymptomatic and usually diagnosed by chance during a blood test for another condition.

Other types

Not all blood cancers are represented by the three main types. Other forms of the disease include myelodysplastic syndromes, myeloproliferative neoplasms, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, histiocytosis and some cases of mastocytosis.

Why is blood cancer often poorly understood?

People typically associate cancer with lumps, tumours and growths, so the concept of a ‘liquid cancer’ can be perplexing. However, cancer is defined as a disease caused by the uncontrolled division of abnormal cells in the body, and any type of cell can be affected, including those in the blood.

Blood consists of three main types of cells – red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. These are carried throughout the body in a clear fluid called plasma, which also contains water, salts and enzymes. There are different types of blood cancer, depending on which type of cell is affected.

Somewhat confusingly, the names of these cancers – for example, leukaemia and lymphoma – do not include the word ‘blood’, so it may not be immediately apparent that they relate to the circulatory system.

Research has shown that this can be a problem at diagnosis, with statistics revealing that 76 per cent of people diagnosed with leukaemia, lymphoma or myeloma are not told that their condition is a form of blood cancer. This leaves only 68 per cent of patients feeling as though they fully understand their diagnosis.

This disconnect is also apparent in the media, with journalists often reporting on cancer diagnoses using the specific cancer type rather than the term ‘blood cancer’. For instance, when the public was told that Oscar-winning actors Jeff Bridges and Jane Fonda had been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, there was little to no mention of this being a type of blood cancer.

Professor Martin Kaiser, Chair of Haematology and Group Leader of the Myeloma Molecular Therapy Group at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and Honorary Consultant Haematologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, said:

“Public awareness and understanding of blood cancer tends to be lower than that of many solid tumours – in part, because there are so many different types.

“Explaining the disease to patients can be difficult because they, understandably, like to have a concept of where things are in their body. When it comes to cancer, we traditionally think of ‘swellings’, and these occur in different places in different blood cancers. For example, they might affect the lymph nodes in someone with one type of blood cancer and the bone marrow in someone with another type.

“It’s possible, though, that this focus on a specific area of the body means patients do not see their cancer as a form of blood cancer. It’s important that we as clinicians take care to make this clear. Having a good understanding of their condition helps patients shape their expectations, and it can empower them to have a role in the management of their cancer.”

Professor Martin Kaiser

How many people get blood cancer?

Blood cancer as a whole is the fifth most common cancer in the UK, affecting more than 40,000 people every year. A new blood cancer diagnosis occurs every 14 minutes, meaning one in every 16 men and one in every 22 women will develop the disease during their lifetime.

Lymphoma is the most common of the main types of blood cancer. About 14,000 people receive a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma each year, with an additional 2,100 people being diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma. These numbers make non-Hodgkin lymphoma the seventh most common cancer in the UK, while Hodgkin lymphoma is not among the top 20 most common types.

Leukaemia is the 12th most common cancer in the UK, affecting more than 10,000 people each year.

Myeloma is the 19th most common cancer in the UK, accounting for about 6,200 blood cancer diagnoses each year.

A regular gift from you will help us to discover the next generation of smart, targeted treatments, so we can help more people survive blood cancer.

What are the survival rates for blood cancer?

Overall, blood cancer has a five-year relative survival rate of 70 per cent, but the rates vary significantly between different types of the disease.

For instance, people with chronic leukaemia (myeloid or lymphocytic) are more than 85 per cent as likely to be alive five years after diagnosis as people who are the same age but do not have cancer. Less positively, people with myeloma or mantle cell lymphoma are less than 50 per cent as likely to reach this milestone.

A person’s age at diagnosis will also affect their outlook. When all leukaemia subtypes are combined, research suggests that about 70 per cent of people aged 15–44 at diagnosis will live another decade or more, compared with about 20 per cent of people aged 75–99.

As a result, acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), which is not only aggressive but also typically diagnosed in people aged 60 and over, has a low survival rate, with about 22 per cent of people living five years or more following their diagnosis.

What are the symptoms of blood cancer?

People are often unaware that they are living with blood cancer because many of the symptoms can be attributed to more benign conditions, such as a common cold or the flu. The symptoms vary according to the type of blood cancer but can include:

- Persistent fatigue

- Persistent, severe or recurrent infections

- Unexplained weight loss

- Shortness of breath

- Lumps or swellings in the neck, armpits or groin

- Unexplained bruising or bleeding

- Fever or chills

- Rash or itchy skin

- Pain in the bones, joints or stomach area

- Night sweats

- A pale complexion, which may be less noticeable in people with dark skin tones

- Coughing or chest pain

- Loss of appetite or nausea

Anyone who experiences these symptoms at a severe level or for more than a couple of weeks should seek healthcare advice.

What causes blood cancer?

Blood cancer occurs as a result of mutations that affect the DNA within blood cells, causing them to behave in an abnormal way.

As with other types of cancer, there is no single known cause of these mutations. Various environmental factors, such as smoking and exposure to certain chemicals, have been linked to an increased risk of the disease, but a person’s genetics are also likely to play a part.

Research has shown that people whose parent, sibling or child has blood cancer are more likely to receive a diagnosis themselves, suggesting that inherited genetic factors contribute to blood cancer risk.

How do doctors diagnose blood cancer?

Doctors may already suspect blood cancer based on someone’s symptoms, but they will carry out tests to confirm the diagnosis.

As well as looking for physical signs of the disease, such as swollen lymph nodes, unexplained bruising and enlargement of the spleen, they will carry out blood tests to check for abnormal levels of white blood cells, red blood cells and/or platelets.

Other possible blood tests include liver and kidney function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and lactate dehydrogenase.

As a follow-up, the doctor will usually order a biopsy, which will involve removing part of a lymph node (for suspected lymphoma) or part of the bone marrow (for suspected leukaemia or myeloma) for evaluation under a microscope. Tests can reveal information about the genetics of the cancer and the proteins on the surface of its cells (immunophenotyping), both of which can help with determining the exact type of blood cancer. This information is key to estimating a patient’s likely outlook and deciding on the best treatment approach.

Imaging tests, including X-rays, ultrasound, and CT, MRI and PET scans, can sometimes form a part of diagnosis too. These can reveal enlarged lymph nodes and show whether cancer has affected the bones or organs.

Can blood cancer be staged?

The staging system for blood cancer differs from that for other cancers because it rarely leads to solid tumours.

Each type of blood cancer has a slightly different system, but there are always three, four or five stages. At the earliest stage, the patient may have an abnormal blood count but no or few other signs and symptoms. By the highest stage, the patient will likely have swollen lymph nodes and an enlarged spleen or liver. By some definitions, the cancer will also have spread to other systems or organs at this point.

Along with the genetic and immunophenotyping information gained at diagnosis, the stage of cancer will help determine the best treatment approach.

What are the treatment options for blood cancer?

Unlike other types of cancer, which are treated on oncology wards, blood cancer is often treated by haematologists – doctors specialising in blood-related conditions.

There are multiple treatment options for people with blood cancer. The type of blood cancer, along with its aggressiveness and stage, will determine which treatment is most likely to be effective for them.

For slow-growing cancer that is not causing significant symptoms, the best option may be active monitoring, also known as ‘watch and wait’. This involves regular checkups to monitor the progress of the disease rather than active treatment. If the cancer does start to progress, the person will begin treatment.

The lack of solid tumours in blood cancer means that surgery is not usually an option, but occasionally, doctors will decide to remove a patient’s spleen if it becomes too enlarged or is making the levels of red blood cells or platelets too low. This surgery is called a splenectomy.

Other possible treatments include chemotherapy, stem cell transplants, radiotherapy, targeted therapies and immunotherapy.

Some patients may also take part in clinical trials evaluating new treatment options that are not yet approved for standard use in clinics.

Can blood cancer spread?

This question is not really applicable to blood cancer, which is considered a systemic cancer.

Blood can travel anywhere in the body and, unlike solid organs, it does not have boundaries. Therefore, in essence, many blood cancers have spread straight from the beginning, which is why surgery is not possible as a treatment.

What are the focus areas of blood cancer research?

According to Dr Alex Radzisheuskaya, Group Leader of the Chromatin Biology Group in the Division of Cell and Molecular Biology at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR), blood cancer researchers are focusing their efforts on several key areas.

One of the main aims is to develop a better understanding of the biology of blood cancer to aid the development of personalised therapies tailored to each patient’s unique cancer profile. This precision medicine approach aims to enhance treatment efficacy while minimising side effects.

Alongside this, researchers are working to discover new biomarkers that could lead to more accurate diagnostic tools, allowing doctors to detect blood cancers at an earlier stage when they are easier to treat.

Other scientists are working on improving existing treatments, with the hope of expanding the use of immunotherapies, refining the stem cell transplant procedure to increase success rates, and using novel drug combinations to overcome treatment resistance.

Dr Radzisheuskaya and her team work at the cellular level, investigating the fundamental biological processes and interactions that lead to AML. She said:

“AML is particularly aggressive. The prognosis for individuals with this disease remains poor, underscoring the urgent need for new and more effective treatments. A crucial aspect of achieving this aim is gaining a comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms that underlie leukaemia.

“The human genome is organised into a complex structure known as chromatin, which consists of DNA, RNA, and protein molecules called histones. In my laboratory, we focus on understanding how the chemical modification of histone proteins – a process called acetylation – contributes to the development of AML.

“As well as regulating chromatin structure, acetylation affects gene expression and cellular identity. However, its precise link to leukaemia isn’t fully understood. By investigating how abnormal histone acetylation contributes to cancer development, we aim to advance the fundamental understanding of AML biology.

“Ultimately, our goal is to uncover potential targets for innovative treatments, paving the way for more effective and personalised approaches to combat the disease.”

While Dr Radzisheuskaya’s work is very much at the ‘bench’ end of the ICR’s ‘bench to bedside’ principle, Professor Kaiser represents research at the other end, working both in the lab and in clinics. He said:

“Treating blood cancer is challenging because it is a complex disease that includes dozens of different cancers, many of which are uncommon or rare, ranging from treatable to very difficult to treat.

“My lab work is focused on blood cancer, specifically multiple myeloma. Our team is working on a better understanding of the origins and drivers of multiple myeloma, and we use this information to deliver the right treatment to the right patients, aiming for better, gentler treatments.

“Working as both a clinician and a scientist at the ICR, I have had the fantastic experience of seeing our team’s findings truly reaching patients.”

Dr Alex Radzisheuskaya

What does the future hold for blood cancer patients?

Survival rates have improved significantly in recent years across many types of blood cancer, and Dr Radzisheuskaya is optimistic that this trend can continue and expand to include the more difficult-to-treat blood cancer types. She said:

“Blood cancer research is advancing rapidly, with various approaches coming together to improve diagnosis, treatment and patient outcomes.

“These advancements are transforming the landscape of blood cancer treatment, bringing hope for more effective, personalised and accessible care.”

Professor Kaiser agreed, saying: “Progress is a lived day-to-day experience in the clinic, which is exciting to see. However, I believe we can make treatments even more tolerable and efficacious than they are at the moment. We just need to keep on with the research.”

Fortunately, neither team shows any signs of stopping.

“I feel privileged to work in this area,” said Professor Kaiser. “Blood cancer research never gets boring – there’s always something new to learn, and I am so encouraged by the hope our work in the lab will translate into real benefits for my patients.”

Dr Radzisheuskaya said: “The chance to contribute to breakthroughs that bring real hope and change is profoundly motivating.”

Your support will help our researchers make more life-saving discoveries, giving people with blood cancer precious extra time with their loved ones.