Our research into ovarian cancer

Our researchers excel in research and drug development for ovarian cancer.

From groundbreaking clinical trials to innovative drug discoveries, The Institute of Cancer Research has been pioneering new treatments for ovarian cancer for decades.

Timeline: How the ICR has led the way in ovarian cancer research

Pre-1950s

- More than 100 years ago, The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR), formerly known as The Cancer Hospital Research Institute, laid the foundations for its pioneering work in cancer research. Achievements in radiotherapy, drug research and cell biology enabled later breakthroughs that would transform ovarian cancer research and treatment.

- In 1947, the ICR, in collaboration with The Royal Marsden, became one of the first centres to establish a close link between cancer research and clinical care, facilitating a bench-to-bedside approach across cancer types.

1950s

- The ICR became the first research centre in Europe to discover and develop chemotherapeutic agents. Through altering the chemistry of nitrogen mustard, a derivative of mustard gas, scientists at the ICR produced melphalan, chlorambucil and busulfan, a class of compounds known as alkylating agents that had anti-cancer properties.

1960s

- Professor Philip Lawley and Professor Peter Brooks continued research into alkylating agents at the ICR. They demonstrated that these drugs worked by chemically bonding to DNA, which prevents it from replicating and triggers cell death. For 20 years, alkylating agents were among the most important chemotherapy drugs available, and they are still used for cancers that are resistant to newer targeted therapies.

- In 1965, the ICR played an important role in the development of cisplatin, which was originally discovered by a research team at the University of Michigan. ICR scientists demonstrated that the drug acted in a similar manner to alkylating agents. Cisplatin became the backbone of combination therapy, often prescribed alongside an alkylating agent, and it was widely used in ovarian cancer treatment.

.jpg?sfvrsn=999b1809_2)

1970s

- The ICR and The Royal Marsden co-led clinical trials of cisplatin in the UK, showing the drug to be effective for treating several kinds of cancer. Cisplatin was approved for use in the US and the UK in the late 1970s, but it could cause severe side effects. ICR scientists Dr Tom Connors and Dr Ken Harrap went on to test around 300 derivatives of cisplatin to try to produce a milder form. This led to the discovery of carboplatin – an extremely effective cancer drug with fewer side effects.

1980s

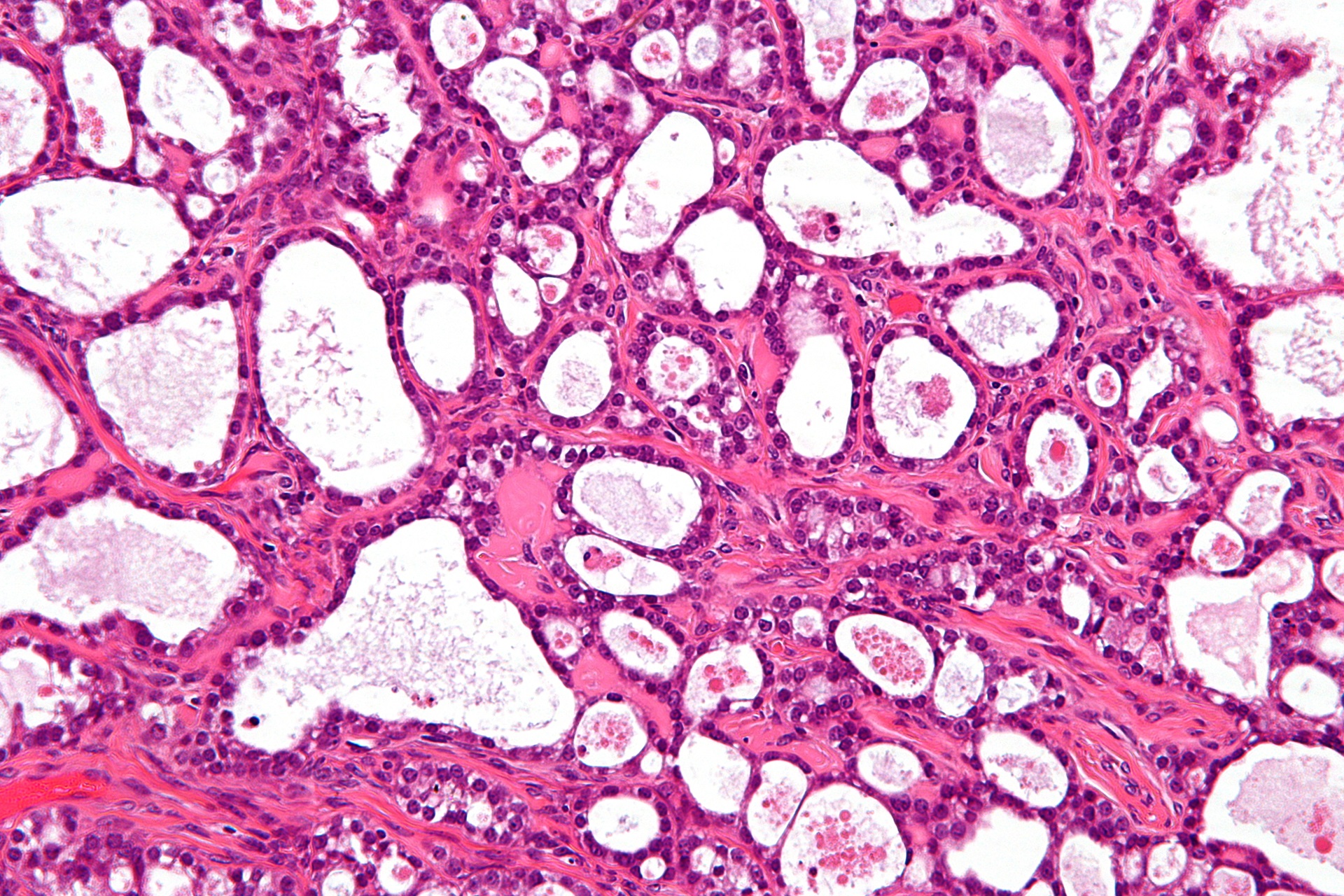

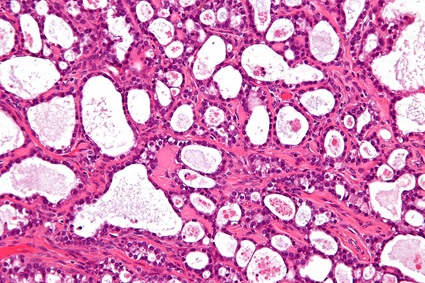

- In the 1980s, carboplatin became one of the most widely used and effective treatments in high grade serous ovarian cancer – the most common type of the disease. The method to clinically administer carboplatin was devised by Dr Hilary Calvert, an oncologist at The Royal Marsden and the ICR. Carboplatin was evaluated in a phase I and pharmacokinetic study at The Royal Marsden in 1981, and it was licensed for use in the UK and the US in 1986 and 1989, respectively.

.jpg?sfvrsn=5ee5f73f_2)

1990s

- 1990 saw the start of a phase III international AHT (Adjuvant Hormone Therapy) trial, coordinated by researchers at the ICR, which aimed to investigate the impact of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) on ovarian cancer survival.

- In 1995, researchers at the ICR discovered the BRCA2 cancer gene. People who carry certain mutations in this gene have an increased risk of developing ovarian and other cancers. The research was led by Professor Michael Stratton and Professor Alan Ashworth. These findings were published in Nature.

2000s

- In 2005, the ICR’s Professor Alan Ashworth started collaborating with Professor Steve Jackson, who founded the drug discovery company KuDOS (later acquired by AstraZeneca). At the time, KuDOS was developing drugs to target a DNA repair protein called poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP). Professor Ashworth and Professor Jackson discovered that disabling both BRCA and PARP DNA repair systems could kill cancer cells, an approach known as ‘synthetic lethality’. This work laid the foundations for the development of olaparib, a targeted treatment for ovarian cancer.

- In 2005, Professor Ann Jackman at the ICR discovered a new drug candidate, BTG945 (later known as idetrexed). This drug works by inhibiting thymidylate synthase, an enzyme critical for DNA replication and cell growth.

- In 2009, Professor Johann de Bono and Professor Stan Kaye carried out the first phase I trial of olaparib, which showed that it prevented tumour growth in cancers associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and that it produced few of the adverse effects of conventional chemotherapy. These findings were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

-945x532.jpg?sfvrsn=fa64405f_2)

2010s

- In 2012, the results of the AHT trial to investigate the effect of HRT on ovarian cancer survival were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The study, led by the ICR’s Professor Ros Eeles, suggested that women with ovarian cancer could take HRT to alleviate menopause symptoms without affecting their recovery. In fact, the results indicated that HRT might improve overall survival rates.

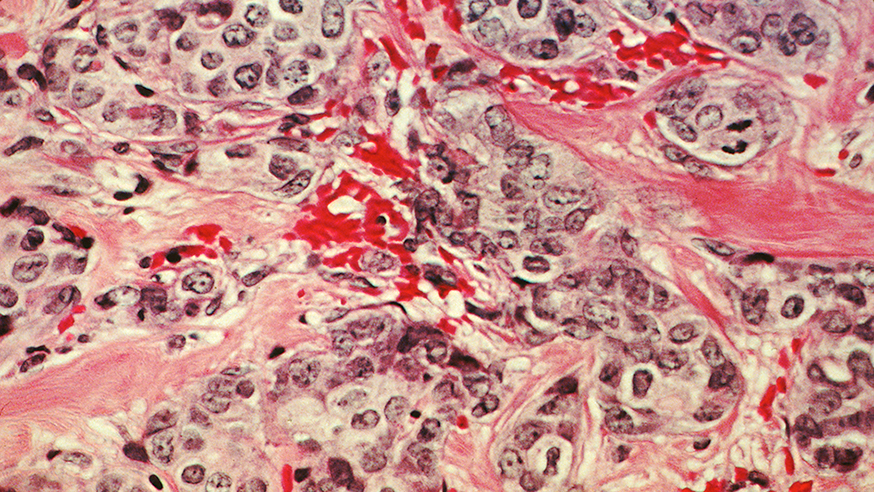

- In 2014, subsequent clinical trials on olaparib resulted in the drug being approved by regulators in the US and Europe to treat high grade serous ovarian cancer in people with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, transforming the outlook for these patients.

- In 2015, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) approved olaparib for women with ovarian cancer who had BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and had responded to three rounds of platinum-based chemotherapy.

- In 2017, Professor Paul Workman’s team at the ICR discovered HSF-1 pathway inhibitors, which act as a ‘master switch’ to control the activity of genes in cells. In follow-up work, Professor Workman and his team were able to kill human ovarian cancer cells grown in mice. These results were published in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.

- In 2019, the ICR’s Professor Udai Banerji started clinical trials of the drug candidate NXP800, discovered at the ICR by Professor Workman following 15 years of research, which is under evaluation as a treatment for clear cell ovarian cancer.

2020s

- In 2020, Professor Banerji used findings from the phase I FRAME trial, which tested a combination of the drugs avutometinib and defactinib, to better understand how these drugs move through the body (pharmacokinetics). Building on these findings, Professor Banerji launched a phase I trial using avutometinib to observe DNA abnormalities in low-grade serous ovarian cancer. These results were published in The Lancet Oncology.

- In 2021, based on the results from the FRAME trial, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) conferred breakthrough designation for the avutometinib and defactinib combination.

- In 2021, phase I first-in-human trials of NXP800 commenced for ovarian cancer patients. The drug was acquired by Nuvectis Pharma, a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on the development of innovative oncology medicines. The trial is being led by Professor Banerji and sponsored by Nuvectis.

- In 2022, Professor Banerji conducted an academic first-in-human phase I study of idetrexed with the results published in Clinical Cancer Research. The study showed that idetrexed has potential as a targeted treatment that improves outcomes for patients with platinum-resistant high-grade serous ovarian cancer and that it has manageable side effects.

- In 2023, pharmaceutical company Algok Bio took ownership of idetrexed, and the drug entered a new clinical trial to test its effectiveness and safety in a larger group of patients with ovarian cancer.

- In 2024, results from a RAMP 201 study (a phase III trial of the combination of avutometinib and defactinib), led by Professor Susanna Banerjee, Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden and Professor in Women’s Cancer at the ICR, have shown promising results in women with low-grade serous ovarian cancer.

Your support helps

Our research is helping more women survive ovarian and breast cancer. Please donate today and support the vital work our scientists are doing to defeat cancer.

Sue's story

“In 2007 I was diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer. I was offered a place on a clinical trial for a new drug, the development of which was underpinned by research at The Institute of Cancer Research. Fourteen years on, I’m still taking olaparib. It’s given me a quality of life I could only have dreamed about.”

— Sue Vincent

-mucinous-ovarian-tumour---945x532.jpg?sfvrsn=5e9bb32b_2)

-carousel-945x581.jpg?sfvrsn=d29fb9e9_2)