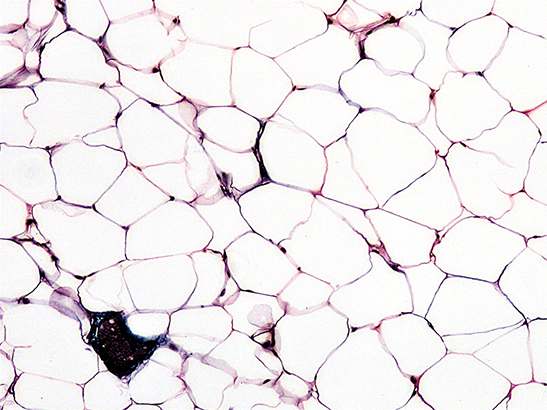

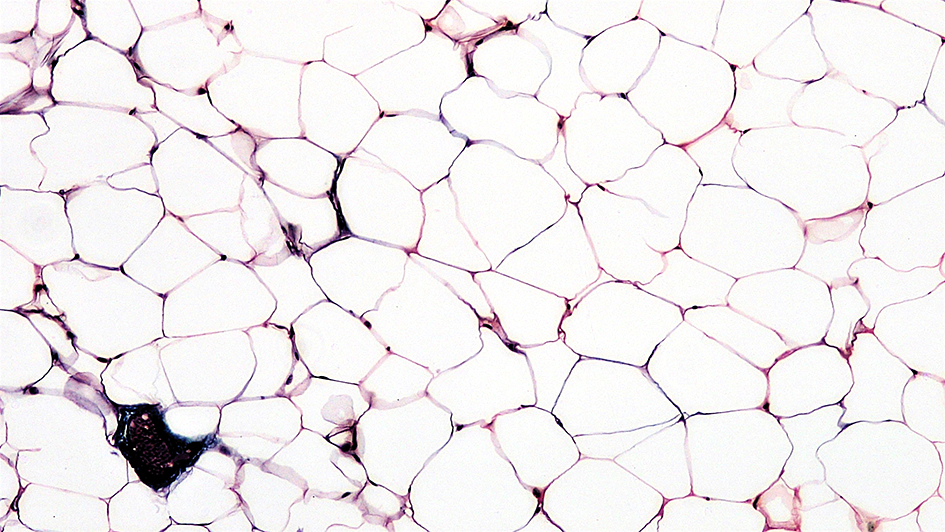

Image: Connective Tissue: Adipose. Adipose tissue, or fat, is an anatomical term for loose connective tissue composed of adipocytes. Credit: Berkshire Community College Bioscience Image Library via Flickr. License: (CC0 1.0)

Obesity is one of the leading factors contributing to cancer development worldwide.

In epidemiological studies, which look at patterns of disease across populations, data suggest that what you eat affects your risk of getting cancer.

But your risk of developing cancer isn’t the only thing impacted by your food. The food you eat also has a significant impact on how you will react to treatment if you develop cancer, and we don’t know enough about it to make meaningful clinical decisions.

So says a recent review paper, authored by Dr Barrie Peck from the Structural Biology Group at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, published in the journal Trends in Cancer. He has since moved to a new role as a Group Leader at the Cancer Research UK Barts Cancer Institute.

“We know that obesity is a major risk factor for developing cancer, but your weight and diet also affect the trajectory of the disease and response to treatment”, Dr Peck said.

“Generally, obese patients respond worse than non-obese patients to cancer treatments, and as a result, they have worse outcomes overall. But we are not yet in a position to make clinical decisions for these patients based on their obesity status, or their diet at the time of treatment.”

Where it all begins

The basic cause of cancer is damage to your DNA. The damage can take lots of different forms, but in all cases, it causes a cell’s replication to go haywire.

Cancer cells undergo all kinds of changes that normal healthy cells do not - they change their energy sources, alter their processes and rewire themselves in unusual ways, doing anything they can to survive.

Sometimes, cancer is predetermined. DNA faults can be traced back as far as the womb for some cancer types, and for others it’s exposure to cigarettes or the sun that leads to the DNA damage.

But what about the direct impact of the food you eat on cancer cells? The big picture – being obese puts you at increased risk – is clear, but thus far, little work has been done to assess the impact of diet on your cancer.

Dr Peck said: “We know that, for example, smokers are much more likely to develop lung cancer, we know that their smoking puts them at a much higher risk than non-smokers.

“In the case of smoking, cessation is obviously is a good thing, but stopping someone for eating is, obviously, not possible and we do not have solid advice about what patients could change to increase the likelihood of their particularly therapy to work.”

Little is known about how the diets of those who are obese should be modulated to get the best out of cancer treatments.

Someone who is obese will be at an increased risk of cancer, and we have a fair idea about what changes they could make to get their weight to a healthier level, and therefore reduce their risk of developing the disease.

But those same dietary changes don’t apply once you’ve already been diagnosed with the disease, in fact those changes could have the opposite effect.

“If you go back to our lung cancer example, in terms of making changes to your diet, you might think ‘I’ve got cancer, I’ve heard that antioxidants, which are present in “superfruits” prevent cancer, the best thing I can do is go and take lots of antioxidants.’ But research has shown that is actually a very bad idea when you are on treatment.

“Having a high level of antioxidants while you’re receiving treatment seriously impedes the drugs’ ability to do their job. This has very recently been shown to be the case in breast cancer as well.”

The same could be the case for obesity, but really, we just don’t know.

We have a proven track-record of awe-inspiring research, which is transforming the lives of cancer patients around the world. This work is made possible by an extraordinary community of generous donors, which includes individuals, trusts and foundations and charity partners.

Treating the patient in front of you

Weight is complicated. Some people can follow a prescribed diet and exercise programme and lose lots of weight, but others won’t. Others might be able to lose some weight but will find it much, much more difficult, and have serious difficulty keeping their weight down in the long term.

Obesity is on the rise all around the globe, and so are cancer diagnoses. Although research has produced treatments which mean more and more people are surviving their cancers, the increase in the numbers of obese patients with cancer is something that needs to be front of mind for clinicians.

“You have to be able to treat the patient in front of you,” Dr Peck said.

“It’s no use to say to a patient ‘well we have done all these tests and we have found that your cancer is this particular subtype, but sorry, we don’t have a treatment.

“We need to have drugs and treatments available, and we need to know if there are changes we could make which would help the treatment perform better in certain patients. It may be the case that changes to diet in obese patients could improve outcomes, but we need to pinpoint what those changes will be.”

Dietary changes have been used in other illnesses, such as the ketogenic diet for severe forms of epilepsy that have a genetic origin, but it’s tricky to find a one-size-fits-all solution to such a complex decision.

“In the case of epilepsy caused by GLUT1 deficiency,” Dr Peck explained, “it’s been shown that it is possible to remove specific sugars from the diet and that patients get benefits from that. The number and frequency of seizures reduce and this can be maintained as long as patients stay on the specific diet.

“But when it comes to obesity, or high fat diets, it may be a more difficult equation. A high fat diet doesn’t just promote cancer development, it promotes cancer aggressiveness too.”

The tumour microenvironment

The cells and tissues directly surrounding the tumour can be friend or foe to the cancer. The cancer will use the blood vessels to get a hold of nutrients, dispose of its waste products, and masquerade itself from the immune system too.

We know that tumours are very sensitive to changes in oxygen concentration. Tumours rely on local blood vessels to get the oxygen they need. When oxygen levels are low, proteins called HIF (hypoxia-inducible factors) are stabilised and switched on, and this process drives the cell to produce substances that help it survive and grow stronger in the face of adversity.

If high levels of these HIF proteins are detected, it’s a signal that the patient is not likely to do well, especially in the case of more invasive and aggressive tumours. Cancer cells in low-oxygen environments are also better able to metastasise and show higher levels of resistance to chemotherapy.

You are breathing as you read this (one would hope). Breathing is an involuntary process – your central nervous system manages this for you. Your body also does a great job of regulating the levels of oxygen in your blood, managing the constant supply of air you breathe and ensuring all of your tissues and organs get an even flow.

The same cannot be said for food. Take an average office worker, for example. She will get up around 7.30am and head out to work, grabbing a latté and a croissant on her way.

Prior to this, she will have spent in the region of eight hours asleep, consuming no food, and will therefore have very few if any nutrients circulating in her blood.

But as soon as she eats her croissant and takes her morning coffee, the levels of nutrients will surge. This happens every time we eat food, multiple times a day.

When a large tumour is growing so quickly that the cells are not being supplied with enough oxygen from the blood, they will also struggle to get access to nutrients circulating in the blood. Cells that are far away from blood vessels will struggle to persist, and they’re likely to be hugely sensitive to changes in the supply of nutrients coming from the food we eat.

Advancing into the era of precision medicine

Dr Peck said: “Oxygen supply is constant and stable so its availability within the tumour is solely dependent on diffusion kinetics from the blood vessels into tumours, but nutrients come in diurnal tidal-like waves throughout the day as we eat and snack.

“The frequency with which we eat food, and the composition of that food, are therefore likely to have a huge influences on tumour cells that live in these unfavourable areas of the tumour. For those who are consuming highly nutrient-dense food and consuming it often, the impact is significant.”

As we advance into the era of precision medicine clinicians need as many weapons as possible at their disposal to help patients successfully survive their disease.

Dietary modulation could be a powerful addition to this tool kit but first we need to understand how diet combined with the genetic architecture of a patient’s tumour influences disease progression and uncover what are the drugs, be they new or established therapies, we can use successfully in combination with dietary modulation.

Many patients inquire about what they can do to increase the likelihood of them surviving their disease. Being able to give accurate dietary advice would empower patients to take back some control of an often devastating life-changing diagnosis, empowering them to make that change.