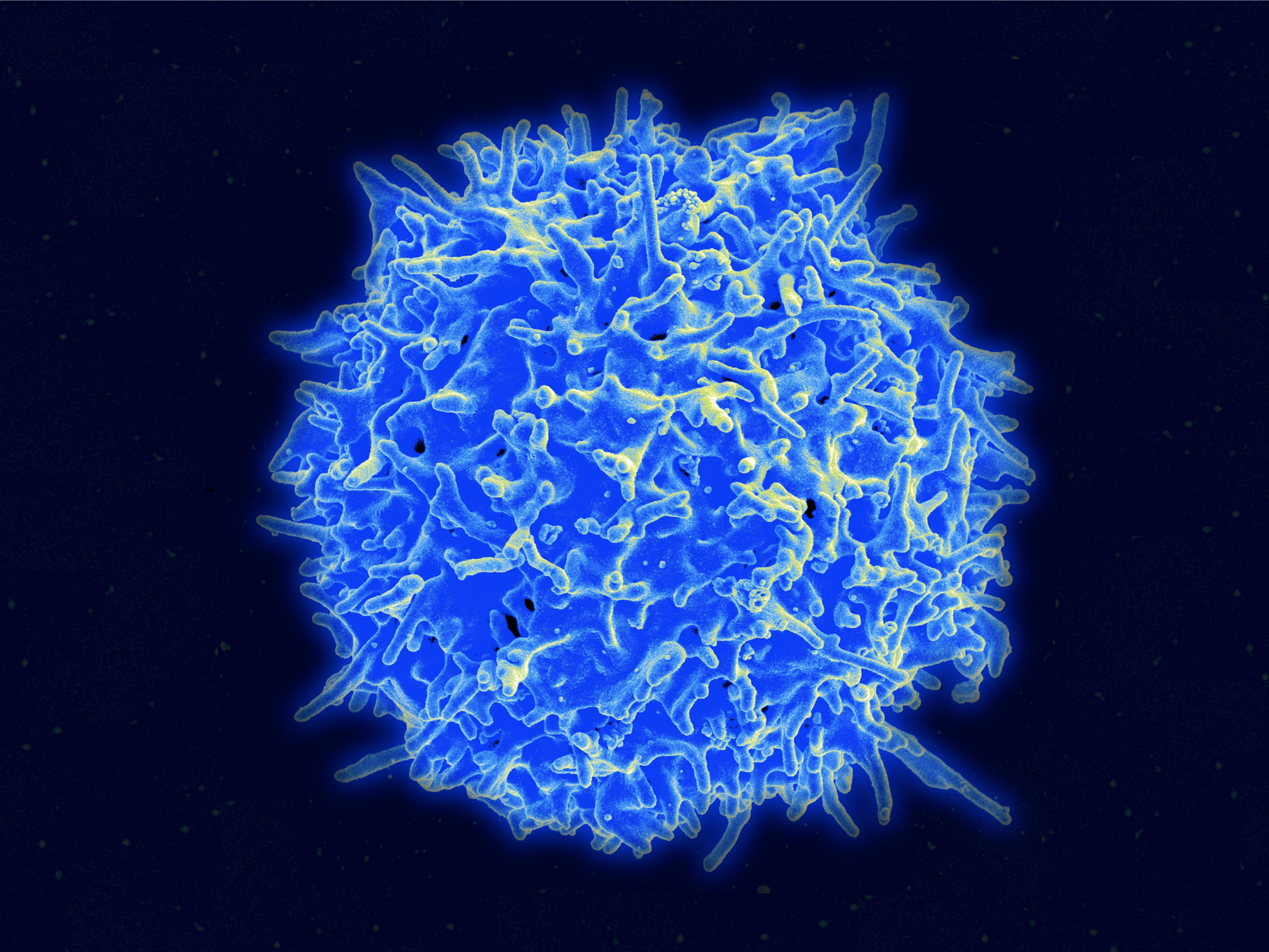

Image: Healthy human T-cell. Credit: Wikimedia

Researchers have discovered how a key element of our body’s response to diseases works, answering a long-standing and important question in the field of studies of the immune system.

A new study by scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London has uncovered an ‘off switch’ for a structure in cells that mediates our immune systems’ response to perceived threat, and kick-starts a cascade of signals that lead to inflammation.

The study could lead to new drugs to treat inflammatory diseases – when the body’s immune response goes out of control – and explains an important aspect of the body’s response to cancer.

Cancer is sometimes described as a wound that does not heal. Tumours are not made up only of cancer cells – they are a complex mix of cancer, immune and other cells, with our bodies unable to wipe out cancer in spite of the activation of our inflammatory immune response.

Our plans for our immunotherapy research are ambitious – but with your support today, we can make these plans a reality and give greater numbers of cancer patients a vital extra lifeline.

Pioneering study

Researchers at the ICR are pioneering studies into the fundamental forces at play between cancer and our immune systems, to try to find new treatments.

This new study, published in Nature Communications, sheds new light into the workings of a cell structure called an inflammasome, which plays a role in a natural process of cell death called pyroptosis – and which in turn signals other cells to fight infection.

In healthy responses to infection, inflammasomes respond to infection and tissue damage by activating pyroptosis, causing cells to swell, burst and die, while releasing signals that summon other immune cells.

But in inflammatory diseases, like diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease, pyroptosis is triggered without infection and rapidly escalates the intensity of inflammation, damaging healthy tissue.

And cancer cells can thrive in the presence of inflammation.

Treating inflammatory diseases

Looking in murine immune cells, ICR researchers found that a family of proteins called SUMO proteins keep inflammasomes in check, binding to them to prevent tissues from becoming inflamed.

They also found that blocking a further set of proteins called SUMO proteases – which themselves deactivate SUMOs – raised the levels of SUMO proteins.

This finding proved that blocking SUMO proteases with new drugs could reduce inflammation, and in the future could treat inflammatory diseases.

The research was funded by Breast Cancer Now and supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and the ICR.

Lead study author Professor Pascal Meier, Head of the Cell Death and Inflammation Team at the ICR, said: “Our study answers a long-standing question in studies of immunity by showing that a family of proteins called SUMO proteins act as a key regulator of inflammation, suppressing spontaneous activation of inflammasomes.

“New drugs that block activation of inflammasomes could, in the future, be used to treat inflammatory diseases that involve aberrant activation of the immune response, including cancer.”

-being-attacked-by-two-cytotoxic-t-cells-(red)-547x410.tmb-hbdesktop.png?Culture=en&sfvrsn=8f59440b_2)