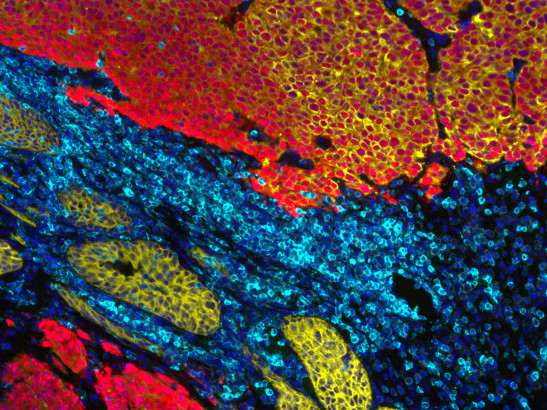

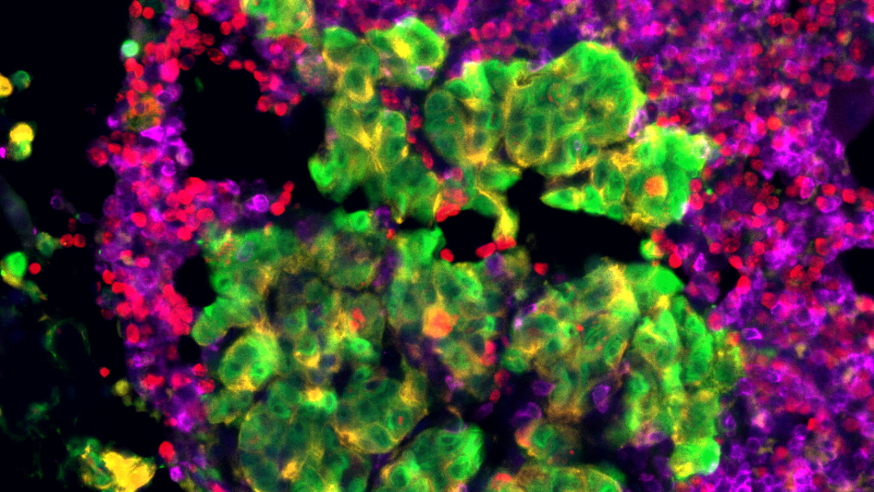

Image: prostate cancer cells. Credits to Mateus Crespo, Ana Ferreira, Daniel Nava Rodrigues and Johann de Bono.

A new prostate cancer blood test can detect early signs that cancer is evolving to become resistant to treatment, a new study has found.

The new ‘liquid biopsy’ test represents a major step forward in the development of tests to analyse whole tumour cells that circulate in the blood – offering a detailed insight into tumours’ genetic make-up.

In future, the new blood test could help detect when drugs are beginning to stop working, so that men with advanced prostate cancer could be offered alternative therapies or combinations of drugs.

It could be further rolled out to help treatment planning in a wide range of other cancers.

A team led by scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, took and analysed whole tumour cells from the blood of 14 men with advanced prostate cancer – all of whom were treated at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust.

In-depth analysis of tumour samples

In the new study, published on Thursday in Clinical Cancer Research, the team used a method called apheresis, which involves passing blood through a machine to extract particular constituents of the blood.

The scientists were able to take 75 times more circulating blood cells out of samples than has been possible before – some 12,500 cancer cells were extracted per 60ml apheresis sample, compared with 167 per 7.5ml using usual methods.

To confirm the test’s precision, the team then compared the genetic characteristics they measured from circulating tumour cells with in-depth analysis of tumour samples from traditional tissue biopsies.

They found that the picture they took from analysing circulating tumour cells closely resembled what was really happening in the tumours, either in original tumours or at sites to which the tumour had spread.

We are training the next generation of researchers; by supporting a PhD studentship, you could help us advance personalised prostate cancer treatment.

Encouraging the development of similar tests

The research was carried out at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) with colleagues in the Netherlands and Germany, and supported by funders including Cancer Research UK, Prostate Cancer UK, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and the Medical Research Council.

The study could reinvigorate the development of tests that analyse circulating tumour cells, or CTCs, as a measure of how cancer is developing.

The development of these tests has slowed in recent years, in part because it has been challenging to capture enough cells from a standard blood sample, as the number of circulating whole tumour cells in the bloodstream is very low.

Many researchers have instead focused on developing alternative liquid biopsies that measure circulating tumour DNA in the blood, rather than cells.

Larger studies needed next

However, circulating tumour DNA lacks some key information that helps to generate a full picture of how a tumour is progressing – such as the number of copies of cancer genes present in cancer cells, and the level of difference between cells from the same tumour.

In the study, the researchers found they had enough cells to make reliable calculations of this information.

Next, larger studies are needed to confirm how many circulating tumour cells are needed for analysis, and to minimise the cost of the procedure.

Further research could also look into the possible benefits of the new blood test in people with other cancer types, and with less advanced disease.

'New cancer blood test'

Professor Johann de Bono, Regius Professor of Cancer Research at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, said:

“We have developed a new cancer blood test, which analyses whole tumour cells to offer a more complete picture of a tumour’s genetic make-up compared with some other liquid biopsies, while being less invasive than painful tissue biopsies.

“Using the new blood test before, during and after treatment will allow us to keep a close eye on the way a person’s cancer evolves in response to drugs.

“In future, the new blood test could allow us to detect treatment failure at an earlier stage, so that we can switch people with advanced prostate cancer to treatments that are more likely to work for them.”

Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

“This new blood test looks to be a promising new tool to track and respond to cancer evolution – the driver of drug resistance.

“This new blood test could identify emerging drug resistance much earlier on than has been possible, and I am keen to see the possible benefit of the new test validated in larger clinical trials.”