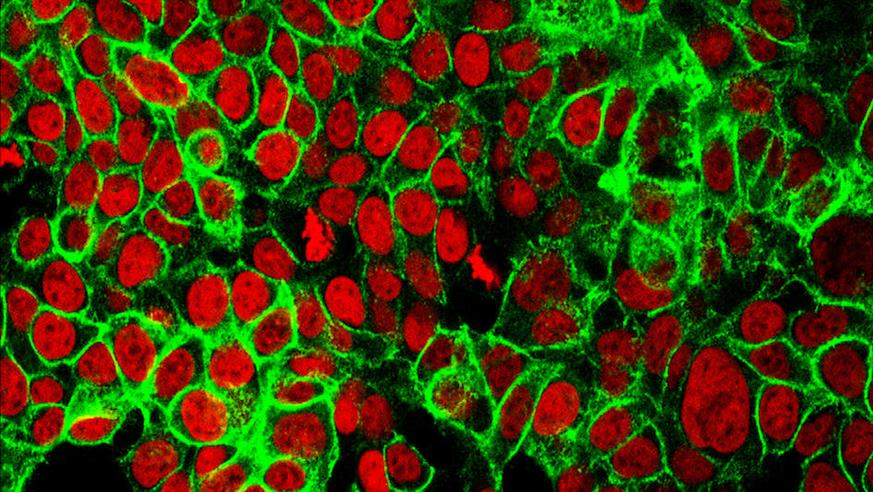

Human colon cancer cells with the cell nuclei stained red and the protein E-cadherin stained green. Source: NCI Center for Cancer Research flickr account. Public domain.

Blood tests could predict how long it takes until bowel cancer returns based on the same principle used in forecasting the weather, a new study has found.

The blood tests, or ‘liquid biopsies’, could also pick out people unlikely to respond to the drug in the first place.

Researchers developed a computer model that can track the evolution of cancer from tumour DNA in blood samples when they are taken frequently and at set intervals.

Our Centre for Evolution and Cancer, led by Professor Mel Greaves aims to help us understand how cancer evolves and adapts, and to find more effective ways to treat it.

Knowing when drugs are likely to stop working could give clinicians more time to prepare for the next step in a person’s treatment, and to consider offering them alternative therapies or enrol them in clinical trials.

Researchers at The Institute of Cancer Research, London and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust analysed tumour and blood samples from people with advanced bowel cancer who took part in an academic clinical trial.

The study is published in the prestigious journal Cancer Discovery today (Thursday), and was supported by funders including Cancer Research UK, the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) and The Royal Marsden, the Wellcome Trust and the European Union.

Tracking tumour evolution over time

The team combined tumour DNA analysis from frequent liquid biopsies – taken at least every four weeks – with mathematical modelling, to track how the genetic make-up of the tumour evolved over time.

Tissue biopsies and blood samples are key tools to help detect changes in tumour DNA, which can signal changes in the way tumours are growing and responding to treatment.

When cancer cells contain certain genetic changes, they can be – or evolve to become – resistant to treatment.

The new study found that a computer model could predict the estimated waiting time until the tumour would stop responding to cetuximab, and the cancer would return.

In 75 per cent of people who initially responded to cetuximab, liquid biopsies picked up changes in the RAS gene before a CT scan was able to show that their bowel cancer had returned.

The researchers also looked at the way changes in a key cancer-related gene, called RAS, affect the response and resistance to cetuximab, a type of drug known as an EGFR inhibitor.

Liquid biopsies picked out 54 per cent of people with bowel cancer whose tumours already had changes in the RAS gene before they were treated with cetuximab, meaning the drug would have been unlikely to work for them.

'The genetic make-up of cancer is highly complex'

Study co-leader Dr Andrea Sottoriva, Chris Rokos Fellow in Evolution and Cancer, and Team Leader in Evolutionary Genomics and Modelling at the ICR, said:

“In our study, we analysed tumour DNA from frequent blood samples, which allowed us to closely track the genetic evolution of bowel cancer within patients.

“Our computer model used information from liquid biopsies to predict how a tumour’s genetic make-up would evolve, and estimate how long it would take for the cancer to return – in much the same way that computer models can forecast the weather.

“The genetic make-up of cancer is highly complex and ever-changing, and understanding how tumours evolve in response to treatment is key in combating drug resistance.”

Forecasting tumour evolution

Study co-leader Dr Nicola Valeri, Team Leader in Gastrointestinal Cancer Biology and Genomics at the ICR, and a Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, said:

“Our study showed that liquid biopsies are better than traditional tissue biopsies at picking out people with bowel cancer whose tumours are unlikely to respond to a drug called cetuximab.

“We also found that analysing tumour DNA from frequent blood samples, which are already taken throughout a person’s treatment, can help predict cancer’s next move.

“Forecasting how tumours will evolve in individual people with bowel cancer could open up the very exciting possibility of using liquid biopsies for personalised, adaptive treatment.”

Predicting response to treatments

Professor David Cunningham, Director of the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and the ICR, who was Chief Investigator of the clinical trial associated with the study, said:

“Despite tailored selection, we know cetuximab only works for 50 per cent of patients so it is crucial to identify those who will not respond to this treatment as early as possible. This avoids unnecessary treatment with a drug we know will not work, and means we can consider alternatives at an earlier stage.

“Tumours shed tiny fragments of DNA into the blood, and these fragments – known as circulating tumour DNA – can be picked up by a simple blood test, or ‘liquid biopsy’. Liquid biopsies are quicker, cheaper and less invasive than taking a sample of body tissue. By analysing the DNA for genetic alterations, also known as somatic mutations, we can follow the progression of a patient’s tumour over time and predict whether they will respond to a particular treatment.

“At The Royal Marsden, targeted, precision medicine is extremely important, so this study is a significant step forward which could benefit some of our patients with bowel cancer.”