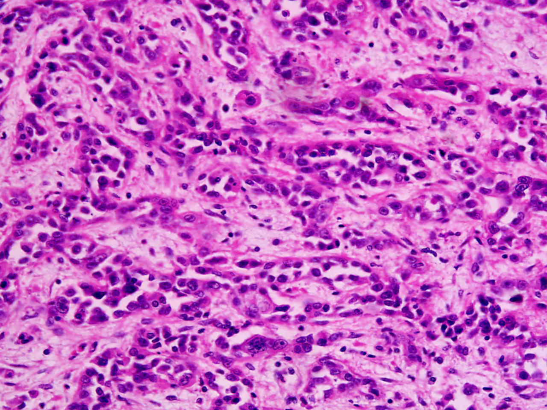

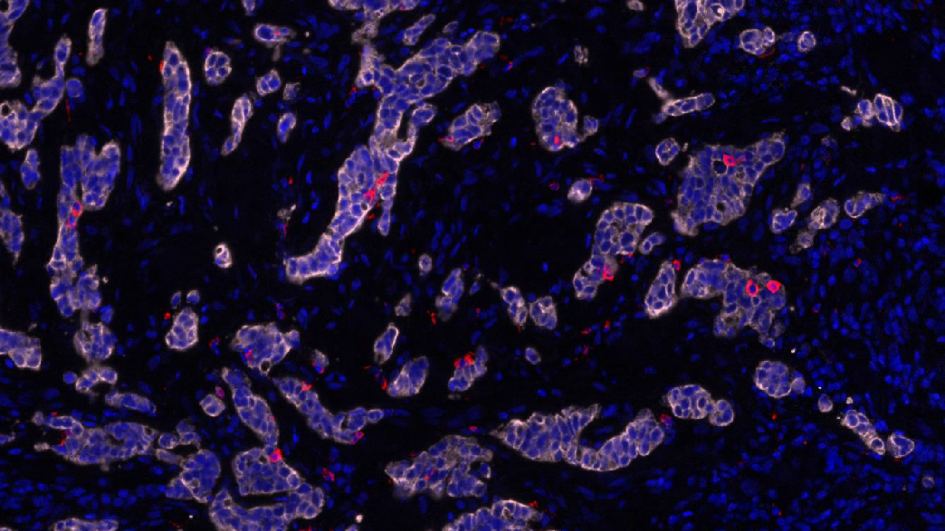

Image: Multiplex immunohistochemistry image of T-cells infiltrating stomach tumours. Credit: Katharina von Loga, Biomedical Research Centre

Aggressive, highly mutated cancers evolve escape routes in response to immune attacks in an ‘evolutionary arms race’ between cancer and the immune system, a new study reports.

Gullet and stomach cancers with faults in their systems for repairing DNA build up huge numbers of genetic mutations which make them resistant to treatments such as chemotherapy.

But their high number of mutations means they look ‘foreign’ to the immune system and leaves them vulnerable to immune attack – as well as susceptible to new immunotherapies.

Scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, found that these ‘hyper-mutant’ tumours rapidly evolve strategies to disguise their foreignness from the immune system and evade attack.

Important role of Darwinian evolution in cancer

The findings underline the important role of Darwinian evolution in cancer, and in how tumours respond to the immune system – and in future, they could help optimise treatment with immunotherapy, and other drugs such as chemotherapy.

The study is published in Nature Communications today (Thursday), and was funded by Cancer Research UK and the Schottlander Research Charitable Trust. It is part of a programme of work at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) to understand how cancers adapt and evolve in response to changes in their environment, such as by evading the immune system or becoming resistant to treatment.

The ICR is the first organisation in the world to design a drug discovery programme specifically to meet the major challenge of cancer evolution and drug resistance – to be housed within its new £75 million Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery.

Strikingly high levels of genetic variation

In the new study, the researchers analysed in minute detail the genetic landscape of four tumours from the stomach and gullet which had a fault in one or more important DNA repair genes – making them ‘hyper-mutated’.

The researchers analysed the genetic make-up of seven different areas from each patient’s tumour, and in sites to which their cancer had spread.

They found that the hyper-mutant stomach tumours had strikingly high levels of genetic variation, with an average of nearly 2,000 different gene faults – much higher than the 436 faults found in skin cancer, the next most highly mutated cancer type analysed in the study.

Different areas of the same tumour showed extreme variation in their mutations –much more than in other tumour types analysed in the new study – enabling rapid Darwinian evolution.

Mutations to evade immune attack

Importantly, the two stomach and gullet tumours with the highest level of infiltration from immune cells had each developed several mutations that allowed them to evade immune attack.

These mutations occurred in genes called B2M, HLA and JAK1/2, which normally help immune cells to recognise and attack cancer cells. When the genes fail to function as normal, the immune system is unable to spot cancer cells despite their large numbers of mutations.

The researchers believe that highly mutated cancers come under particularly strong selective pressure from the immune system – and can draw on huge genetic variation to evolve more rapidly than other cancers, making them particularly hard to treat.

But hyper-mutated stomach and gullet tumours are highly sensitive to novel immunotherapies – showing that the immune system can effectively fight even the most rapidly evolving tumours.

The new findings add to evidence that there is an evolutionary consequence to high mutation rates in sparking an arms race with the immune system – and that this helps explain why these cancers are unusually sensitive to immunotherapy.

Let’s finish it: help us revolutionise cancer treatment. We aim to discover a new generation of cancer treatments so smart and targeted, that more patients will defeat their cancer and finish what they started.

Staying one step ahead of cancer evolution

These results will help the team to investigate further the effect of cancer evolution on immune response in data from a new clinical trial looking at the possible benefit of immunotherapy in similarly hyper-mutant bowel tumours.

In future, the researchers hope their findings could also help combat resistance to chemotherapies – by using similar strategies to the immune system, and staying one step ahead of cancer evolution.

The ICR now has less than £10 million left to raise to finish the Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery and equip it with the state-of-the-art facilities needed for its ambitious Darwinian drug discovery programme.

Dr Marco Gerlinger, Team Leader in Translational Oncogenomics at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

“Our new study has shown that in highly mutated tumours, cancer and the immune system are engaged in an evolutionary arms race in which they continually find new ways to outflank one another.

“Watching hyper-mutated tumours and immune cells co-evolve in such detail has shown that the immune system can keep up with changes in cancer, where current cancer therapies can become resistant – and that we could use immunotherapies to shift the balance of this arms race, extending patients’ lives.

“Next, we plan to study the evolutionary link between hyper-mutant tumours and the immune system as part of a new clinical trial looking at the possible benefit of immunotherapy in bowel cancer.”

'We can tip the evolutionary balance in our favour'

Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

“Cancer evolution is the biggest challenge in cancer research and treatment today – and deepening our understanding of how tumours evolve in response to treatment is absolutely key to finding ways of overcoming drug resistance.

“This fascinating new study shows how cancers can co-evolve with the immune system, with each responding to changes in the other. Without treatment, cancers will be destined to win this evolutionary arms race, but we can tip the balance in favour of the immune system through carefully designed use of immunotherapy.

“I am keen to see our researchers harness their new insights into cancer evolution to help predict cancer’s response to immunotherapy and ultimately to enhance the way we use immunotherapies to maximise their impact.”

Professor Charles Swanton, Cancer Research UK’s chief clinician, said:

“This study emphasises the importance of understanding how cancers evolve, and highlights likely selection pressures imposed by a patient’s immune system and the developing tumour.

“The challenge in improving outcomes for people with cancer, is to fully understand cancer’s evolutionary rulebook. This will mean studying many more samples from patients with different cancers, as so far these researchers have analysed samples from four patients with a relatively uncommon form of cancer.

There’s still a long way to go, but we hope that as the rules of cancer evolution are uncovered, we can discover new ways to treat and care for patients with the disease.”