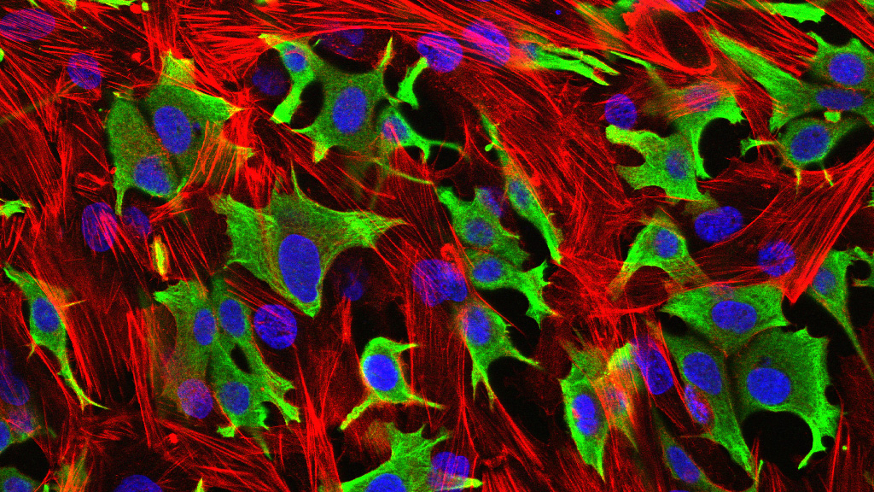

Breast cancer cells (green) invading through a layer of fibroblasts (red) (photo: Luke Henry / the ICR, 2009)

Cells from the most common form of breast cancer can reprogram their metabolism to help resist hormone treatments and become more aggressive, a new study shows.

Scientists from the University of Florence in Italy and The Institute of Cancer Research, London, found that hormone therapy can cause oestrogen receptor (ER)-

positive breast cancer cells to switch to a type of metabolism called glycolysis to produce energy to survive.

Long-term exposure of ER-positive breast cancer cells to hormone therapy triggered metabolic changes which increased their ability to spread and resist treatment, but targeting glycolysis did not reverse the effects.

Fragments of genetic materials called microRNA triggered the changes. Research found the activity of microRNA 155 (miR-155) played a vital role and could be used as a marker to identify which patients are most likely to develop treatment-resistant cancer.

The study, published in the journal Cancer Research, received funding from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro and Fondazione Umberto Veronesi in Italy, and was part-funded in the UK by Breast Cancer Now, with additional support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the ICR and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust.

In nearly 70% of cases of breast cancer, the disease expresses receptors for the hormone oestrogen and relies on ER signalling to grow and survive.

Hormone therapies are the main form of treatment for many patients with these breast cancers and work by targeting the ER pathway to deprive breast cancer cells of oestrogen, but these treatments often become less effective over time as resistance develops.

Metabolism 'switched'

The researchers treated ER-positive breast cancer in cell cultures and mice with hormone therapies, to study how breast cancer metabolism changes in response to treatment.

They saw ER-positive breast cancer cells that were resistant to hormone therapy displayed increased levels of glycolysis metabolism, which occurs more often in aggressive tumours, compared with cells that remained sensitive to hormone therapy.

Combining hormone therapy with compounds that block glycolysis killed more treatment sensitive cells than using either separately, but cells resistant to hormone therapy were able to switch their metabolism away from glycolysis though the activity of microRNA miR-155 to keep growing.

The microRNA miR-155 also helped treatment resistant cells to spread to other tissue more easily than hormone therapy sensitive cells.

Hormone therapy-resistant breast cancer displayed higher levels of miR-155 than cells that were sensitive to treatment, while patients whose tumours expressed high miR-155 levels faced worse treatment outcomes than other patients with breast cancer.

Professor Clare Isacke, Professor of Molecular Cell Biology and Academic Dean at the ICR, said: “Hormone therapies are the first line of treatment for post-menopausal women with ER-positive breast cancer, but some patients develop resistance so we need new ways to target the disease.

“This study shows that ER-positive breast cancer cells can rewire their own metabolism to drive resistance.

“A regulator of gene expression called miR-155 triggered metabolic changes in hormone therapy-resistant cells that led to more aggressive disease, and was also linked to worse outcomes in patients with ER positive breast cancer.”

The findings could help to identify those patients with aggressive breast cancer likely to relapse after hormone therapy, and others who might benefit from additional treatments that target tumour metabolism.