Scientists of a certain vintage are inclined to launch into philosophy, ruminating on the meaning of life, the future of mankind and other lofty issues. These may be worthy intellectual efforts but they’re also a sure sign that the protagonists have now stopped playing the main game.

Any accomplished scientist who has a taste for philosophy should maybe pause to recall the wisdom of Socrates who, at the end of his life, before taking of the hemlock, said that the only thing he was sure of was the depth of his ignorance.

Any philosophical pretensions I might have are tempered by Socrates’s lament. It is salutary to appreciate that the more you know, the more you realise that you don’t know. I’ve never felt so ignorant about biology and science generally as I do now.

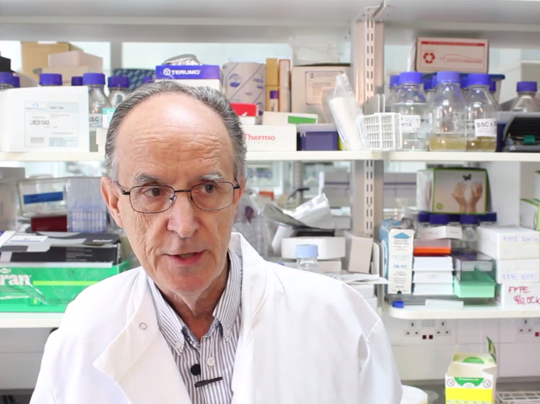

It’s therefore with some trepidation that I’m taking time out, so to speak, to reflect on what it takes to succeed in science. The Director of Communications here at The Institute of Cancer Research, Richard Hoey, thought that since The Royal Society has awarded me a Royal Medal, I must know something about the subject.

An all-consuming passion for science

Well, here’s the secret: there is no secret. No formula for success. No grand plan or route map. It’s more akin to a cross between chaos theory and Alice’s wonderland; you start with small steps, follow your nose or instinct and one thing leads to another. And much that you encounter on the journey is counter-intuitive and not what it seems.

Well, maybe there’s a little more to it than that.

It’s instructive to look at scientists who’ve been truly stellar in achievement. Albert Einstein is perhaps the nearest we have had to a genius and was an extraordinarily creative thinker. However, he himself confessed that he had ‘…no special talents. I am just passionately curious’. My undergraduate mentor Peter Medawar was intellectually brilliant and extraordinarily articulate and eloquent. Fred Sanger was an engineering or technology whizz-kid.

What do these Nobel laureate scientists have in common? Not a lot actually. Except they all had an all-consuming passion for science. And that’s all I share with them. It’s passion that sustains you when you hit a squall, are becalmed or progress is tediously slow.

I have great admiration in these respects for Charles Darwin. He was not especially intelligent or gifted. He certainly had a passion for natural history but more than that he did what I think really matters: he was audacious enough to risk asking a big question. And having posed the question, he doggedly pursued it, like a dog with a bone, for the next 30 years.

So, for what it’s worth, here are a few reflections on my accidental journey in science. The most weird thing is I’m not even sure I am really a scientist at all. Or, if I am, then my underlying motivation has an emotional core. What first attracted me to the natural world as a child – to its galaxies, and its dragonflies – was a sense of wonder and beauty. And that hasn’t diminished one jot with academic scrutiny. What I seek for in the multi-layer, dynamic complexity of biology is an explanatory picture that is both simple and eloquent. Don’t give me an ugly answer, please.

What I strive for in writing science, at least in reviews, commentaries and books, is a lightness of touch. When I read it out loud, as in a conversation, it has to have a rhythm, a musical quality. And if it can be spiced with humour, all the better.

Find out more about the Royal Medal awarded to Professor Mel Greaves for outstanding research by The Royal Society in our news story from 17 July 2017.

My focus on childhood leukaemia

My decision, in the mid 1970s, to focus on childhood leukaemia was informed by perceived opportunity and need. But my primary motivation was the thought that these little patients, clinging tenaciously to life, could be my own children who were, at the time, the same age. And science is supposed to be detached, cold, objective and unemotional isn’t it? Oh no it’s not.

And, here’s the confessional bottom line: I’m a dreamer and story teller. As were Einstein and Darwin and most of us ordinary mortals in white coats. And therein lies the challenge: how your story is to be heard in the cacophony of noise. It’s not to shout the loudest but rather to have a distinctive voice.

And just one comment on narrative style. The best stories grab you on the first page – check out Ian McEwan’s ‘Enduring Love’ and Isobel Allende’s ‘Eva Luna’. And for a science story, verbal or written, to be engaging, the first ‘page’ should be the question, puzzle or challenge. A question that, should it be answered, would make a difference. A question that matters. I lose heart if I don’t get that in the first few minutes of a seminar or lecture. Solving puzzles and telling stories, it’s H. sapiens’s best trick.

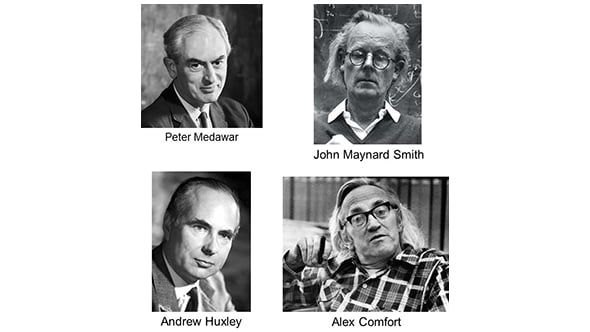

Of course there are, as in any art form, a few basic skills that have to be picked up. And it’s easiest by mimicry. The photos above are portraits of four scientists who taught me as an undergraduate at University College London in the 1960s.

What I gained or gleaned from those four was much more than the science facts they offered. From Peter Medawar I realised what a huge advantage it was if you could think and communicate clearly. From John Maynard Smith, I had my first exposure to the theme song of biology – evolution. From Andrew Huxley, in human physiology, I realised that experimental rigour was essential if you had ambitions to work in a lab. And from Alex Comfort, political activist, poet and later to be author of ‘The Joy of Sex’, I learned that science should be fun and a creative experience.

In so far as I have had a ‘big’ question to grapple with, it has been the cause of childhood leukaemia and the conviction that the development of cancer has an indelibly Darwinian or evolutionary character. And I’ve stuck with it for several decades now. And won’t let go.

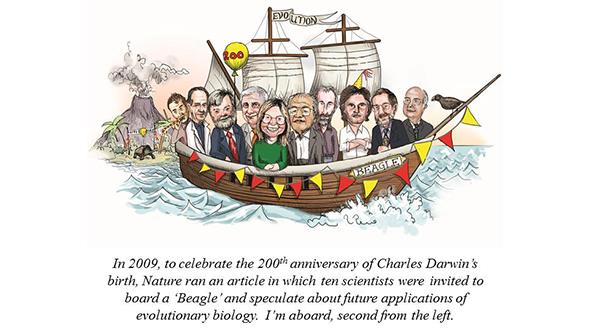

All scientific careers are voyages of discovery; the journey more important than the uncertain destination. And laboratories – or observatories, marine submersibles or the international space station – are Beagles for their occupants.

Which brings me to one other aspect of the successful execution of science that really matters – and serves as a source of great pleasure and enjoyment. Science is a very social activity, both in its context or application and its operation.

Nothing happens, nothing at all, certainly for me, without an in-house team of colleagues and a network of national and international collaborators with an ethos of openness and mutual respect.

The King may give you a medal for sailing your ship, as captain, to new territories. But without enabling technology and a talented crew… you would at best drift, and maybe sink.