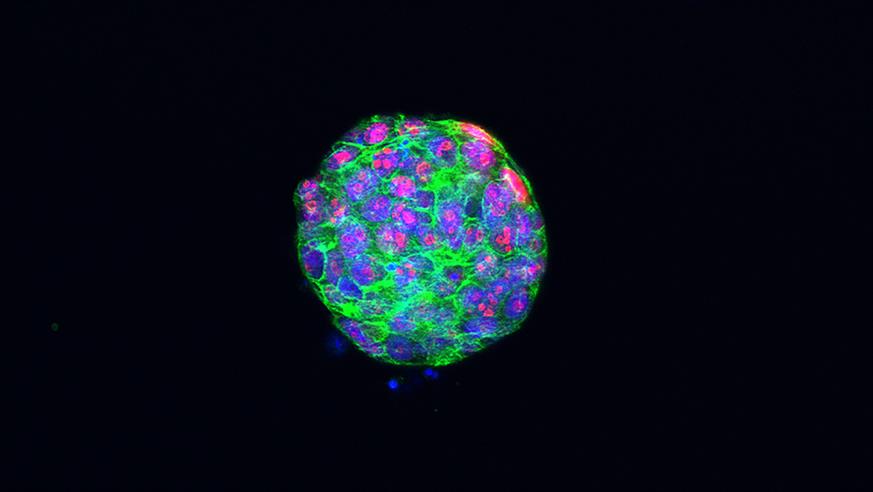

Proliferating cells in a tumour organoid of triple-negative breast cancer. Credit Dr Rebecca Marlow.

One non-fat, tall iced coffee with two pumps of hazelnut syrup, please. From the house we live in to our go-to Starbucks order, the life we create has been tailor-made to our specific needs. The growth of consumerism relies heavily on personal and customised service.

This idea of mass customisation has hit the healthcare sector and efforts to treat patients as individuals are gaining popularity. As just one example, scientists have recently discovered the use of organoids, lab-grown mini tumours, to help design individualised cancer treatment plans.

One size does not fit all

Cancer is frightening and is often seen to prelude death. There’s a widespread fear associated with the unpredictability of this illness and it all boils down to treatment and how individuals respond to it. Although once considered an essentially homogenous disease for which patients were treated the same, evidence shows the complexities of cancer varying from patient to patient. What works for one patient may not work for the next. The more cancer research progresses, the more aware we are of the diverse mechanisms underpinning a patient’s prognosis. These new findings have shaped current medicine and influenced the transition towards personalised therapies.

Good things come in small packages

We are living in a world where unimaginable science becomes reality. Researchers continue to innovate and stretch the imagination. An up-and-coming technology in the bioengineering field is that of organoids which be simply defined as lab-grown mini tumours derived from patient cells. These miniature models represent a tumour in a patient’s body and allow us to examine their appearance and behaviour. This incredible advance opens many new opportunities in cancer research. Although small, these mighty organoids give us hope for more targeted and personalised cancer treatments.

Tumour in a dish

The process in which organoids are created is pretty remarkable. Laboratories receive tumour tissue samples from surgery and the tissue is then broken down, via enzymatic reactions, into individual cells or small clumps of cells. To create a microenvironment that mimics the human body, these cells are held at a normal body temperature and are provided with plenty of nutrients. Voila! Under the perfect conditions, we now have our mini tumour in a dish.

Establishing such cancer organoid lines from an individual patient’s tumour is important for our understanding of the original tumour. With this tumour-in-a dish approach, scientists have the ability to screen multiple drug combinations and create a personalised treatment plan for an individual patient.

Scientists at the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have devised an automated screening method in which hundreds of drugs can be screened in less than two weeks. The use of robots has accelerated this process, allowing for minimal manipulation. Through these exciting advances, it may be the case that in the future, drugs are tested on tumour organoids before patietns are treated with drugs as a means of working out which are likely to work best for an individual.

However, before organoid systems can be implemented in routine clinical use, there needs to be significant evidence proving treatment response in tumour organoids is comparable with that of the original tumour.

A multidisciplinary team, led by Dr Nicola Valeri, Team Leader in Gastrointestinal Cancer Biology and Genomics at the ICR, and a Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, aimed to answer that exact question. They used patient-derived organoids to evaluate treatment response for metastatic gastrointestinal cancers.

Their study shows that 88% of the time the original tumour will respond positively to a drug that elicited a positive response in the organoid, and 100% of the time, a drug that did not work in the organoid would not work in the original tumour. A promising outcome like this strengthens a case for the use of organoids for personalised therapy.

Future of cancer treatment

One combination dabrafenib and trametinib therapy, please. These two targeted therapies may induce a response in a specific subtype of cancer called BRAF V600E-mutated biliary tract cancer. Biliary tract cancer is an aggressive disease with poor clinical outcomes. How amazing would it be to treat patients based on their tumour organoid treatment response?

For those diagnosed with cancer, especially rare cancers like biliary tract cancer that do not have a standard of care, tailoring treatment like this would be life-changing. It could prevent patients from receiving drugs that may not work for them; sparing them from serious side-effects and mental exhaustion from unsuccessful treatments.

More broadly, using organoid technology for precision medicine could guide doctors during treatment planning and alleviate the fears patients face during diagnosis. When our Starbucks coffee can be made-to-order, why not our cancer treatments? Organoids, a powerful tool in modern medicine, advance the prospects of personalised cancer therapy.

Nithya Paranthaman is a PhD student in the Division of Molecular Pathology.