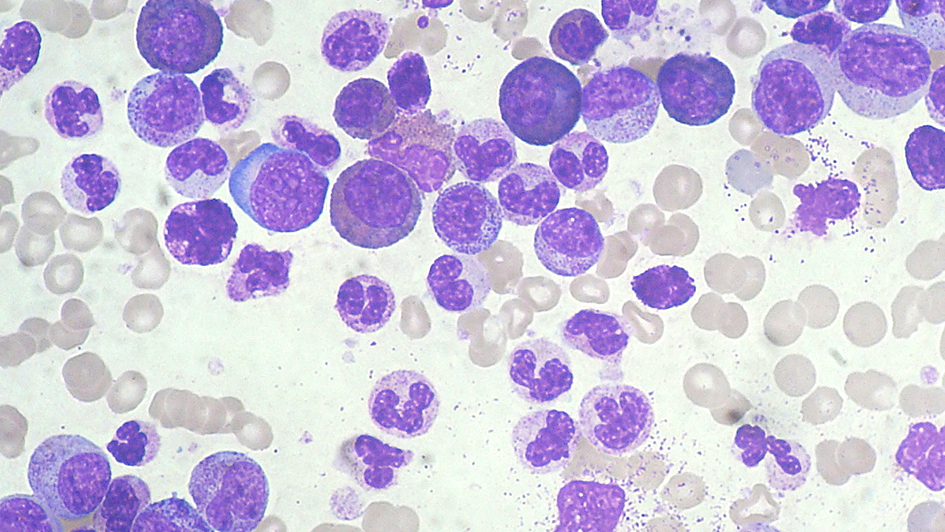

Myeloid leukaemia smear. Image credit: Paulo Henrique Orlandi Mourao. Licence: CC BY-SA 3.0.

Your immune system is divided into two parts – innate and adaptive.

Your innate immune system is like a Roomba – it roves around picking up any old dirt and will cross back over the same paths again and again. It’s not specific to any type of dirt, it just picks up anything it comes across.

Your adaptive immune response, on the other hand, is like a trained housekeeper with a Dyson. If the top of the headboard in room 207 was dusty last time, they’ll remember that next time, and target it. Your immune system creates specialised weaponry to defeat the enemy and remembers the next time he shows his face.

So why doesn’t your immune system see cancer as a bad guy?

Cancer cells are of course extremely harmful to your body, but they’re also really good at hiding away from your immune system. Cancer cells are able to cause changes to the tissues surrounding them that dampen down your immune cells there, making it really difficult for them to recognise that anything is going wrong.

Cancer cells are also able to interfere with your immune system in ways that stop immune cells sending alert signals, meaning your body never notices anything is amiss and the cancer can happily grow and thrive.

We are building a new state-of-the-art drug discovery centre to create more and better drugs for cancer patients. See the plans for our new building floor-by-floor.

Forcing the immune system to respond to cancer

A new study by researchers at The Institute of Cancer Research, working in collaboration with scientists at the University of Leeds, examined a virus called coxsackievirus A21. This is an oncolytic virus, capable of infecting some cancer cells and killing them by literally bursting them open.

In patients with multiple myeloma, the virus burst the cancer cells open, but this effect wasn’t seen in cancer cells from a different type of cancer, acute myeloid leukaemia.

But what the researchers did see in acute myeloid leukaemia was that the virus caused the immune system to respond. The virus infected the cancer cells, and attracted the immune system to the site of the cancer, sending the “danger signal” and priming it to fight back against the cancer cells.

Professor Alan Melcher, the lead ICR researcher on this study, said: “This work helped us understand how best to stimulate the immune system to attack cancers which otherwise remain cloaked from it. We are hopeful that this study will help inform the best approaches for patient treatments in future, by helping us gather information about how patients will respond to different innovative treatment types.”

What’s more, it wasn’t just the innate immune system that was stimulated, but the adaptive immune response too, meaning the immune cells remember the threat and are ready and waiting with specialised weapons for next time.

The study used a mixture of cell lines and samples from real patients, which provides invaluable data on how these viruses could be used in future treatments.

Outsmarting cancer’s sophisticated ways of evading destruction will be a big part of the programme of work at the ICR’s new Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery, where scientists from a multitude of disciplines will try to outsmart cancer’s rapid evolution.

Why your blood donation is important for cancer research

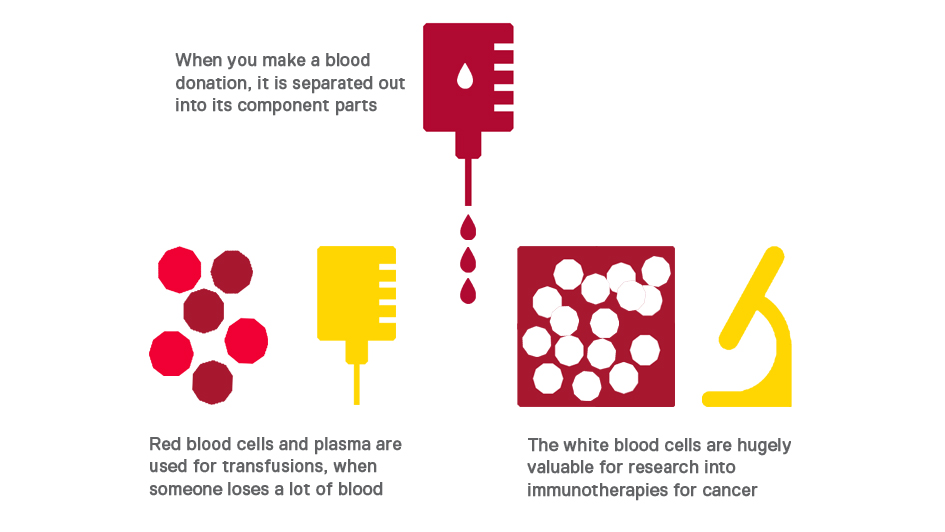

The immune cells used in the study were white blood cells retrieved from blood donations. When you donate blood, it’s separated out into its different components. Red cells are used in transfusions to patients after heavy blood loss from an accident or childbirth.

The white blood cells are usually a waste product, but in this study they were of huge value, allowing researchers to examine how real immune cells from real people responded to coxsackievirus A21.

Professor Alan Melcher said: “This work made use of patient samples and immune cells from real blood donations, in conjunction with cell lines to show that while oncolytic viruses may not always show direct lethal activity, they are capable of inducing an immune response which then targets the cancer. This study bypassed mouse models, meaning the data are more relevant to real cancer cases.”

There’s something nice to remember next time you go to donate blood – not only could you be helping save someone in an emergency, but you might be helping life-changing cancer research too.

This work could be used to inform how patients will respond to new and innovative treatments using viruses to attack cancer, and could lead to long-term benefits as the immune system remembers the danger signals, like a vaccine against cancer.