Early radiotherapy pioneers often gave single large exposures of radiation by placing low-energy cathode ray tubes or radium-filled glass tubes in close proximity to tumours. Not surprisingly, tumours were rarely cured with these early approaches without incurring extensive normal tissue damage.

It wasn’t until the 1920s, that Henri Coutard applied the concept of delivering radiotherapy in fractions – rather than all in one go – over the course of several weeks. Using this strategy, he was able to cure patients with a variety of head and neck cancers and popularised the fractionation approach to radiotherapy across the world.

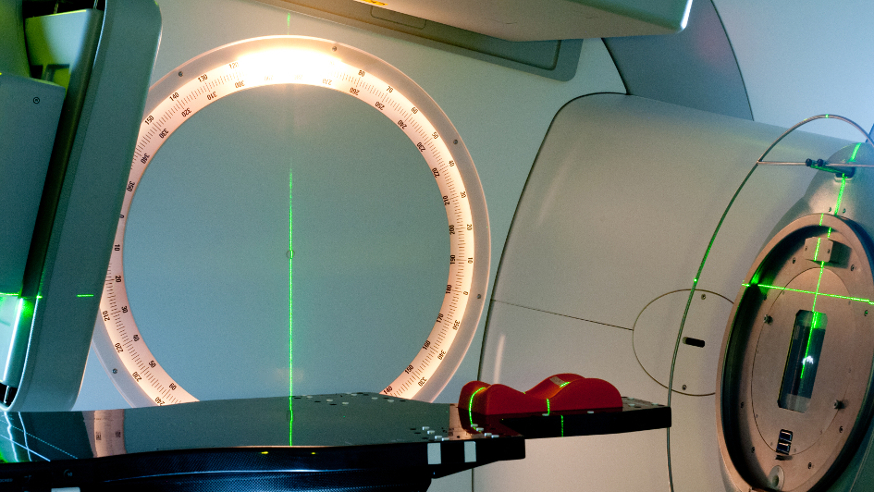

Standard radiotherapy follows Coutard’s lead in that it’s given in fractions – one treatment is given Monday to Friday, over the space of seven and a half weeks. But now researchers are considering a ‘hypofractionated’ radiotherapy approach, where more radiotherapy is given per fraction, but in fewer fractions. Although the dose per fraction is higher than standard radiotherapy, the overall total dose is lower.

Hypofractionation has been proposed for a variety of cancer types, such as breast and early-stage lung cancer, but using hypofractionation to treat prostate cancer has remained controversial because of concerns regarding efficacy and the potential urinary and bowel toxicity.

Professor David Dearnaley, Professor of Uro-Oncology at The Institute of Cancer Research and an honorary consultant at The Royal Marsden, recently published his thoughts on using hypofractionation in prostate cancer in The Lancet Oncology. He begins by postulating why hypofractionation could be effective in treating prostate cancer, and summarises the current evidence on why this might be so.

In the past decade there has been much speculation that prostate cancer might have high radiation-fraction sensitivity, suggesting a therapeutic advantage of hypofractionated treatment. Many retrospective reviews of patient cohorts have supported the hypothesis, and a recent systematic review of six small Phase III trials concluded that hypofractionation seemed safe but that further evidence was needed to establish the clinical benefits.

Hypofractionation studies have so far been limited by their relatively short follow-up and a modest increase in dose per fraction. There is the added difficulty of establishing comparisons among different radiation techniques, hypofractionation schemes, and toxicity scales.

But the future is looking hopeful, as three large Phase III trials of modest hypofractionation have now been completed. In the UK, the CHHiP trial, a study led by Professor Dearnaley and the ICR’s Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit, compares different fractionated doses in 3,200 men. A Dutch group is comparing hypofractionation with standard fractionation in the HYPRO study, and in Canada, investigators are comparing two fraction dosing regimens.

Preliminary results from the HYPRO and CHHiP studies are now available, and overall the results are reassuring for hypofractionation. In the CHHiP trial there was no difference in immediate or late side-effects – up to two years after treatment – between hypofractionation and standard fractionation groups. Early side effects were higher in the HYPRO study probably because of a deliberate dose escalation.

Speaking to Professor Dearnaley, I asked him about his future hopes for hypofractionation. He told me: “After our promising early safety results from the CHHiP trial, we are looking forward to the next round of results to see if this method ultimately offers patients better tumour control or fewer side-effects.

"If all three large studies found hypofractionation to be beneficial, we could see changes in how we deliver radiotherapy on a national and international scale. Men would have fewer hospital trips and less radiotherapy overall, something men and their families will appreciate, and reducing the number of trips to the hospital will also be financially beneficial to patient and the NHS.”

Oncologists and health commissioning groups will need to be patient as they wait for the long-term results from these large Phase III trials.

But if the findings are positive, we are likely to see a change in clinical practice – and major benefits for both patients and the NHS.