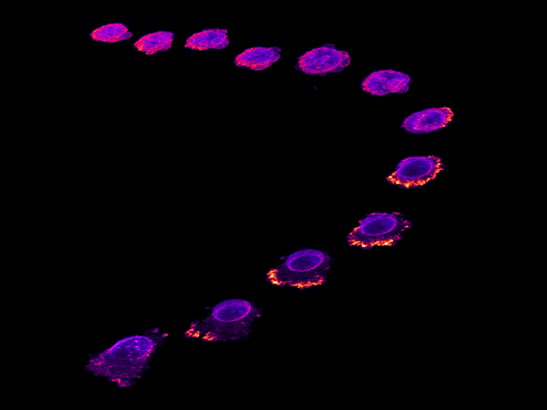

Image: Time lapse image of a breast cancer cell escaping the blood vessel layer during metastasis. Credit: Dr Maxine Lam

“Breast cancer risk ‘increased by up to 80 per cent for women having children’ compared to those without kids”

“Having a first baby at 35 raises breast cancer risk for decades”

“Women's breast cancer odds INCREASE by 80% after giving birth for the first time, study reveals - and women over 35 are at the greatest risk”

Reports on a large new study on pregnancy and breast cancer risk came accompanied by these sorts of alarming headlines. But should mums, and older mums in particular, be worried about the latest findings?

Pregnancy, with its whirlwind of hormonal changes, is known to affect breast cancer risk. Having children lowers women’s risk of breast cancer overall – but studies have suggested that in the short term, it actually raises women’s risk.

In the recent headline-grabbing study, our scientists looked at this dual effect in more detail, analysing data from from 889,944 women who took part in 15 studies – including the Breast Cancer Now Generations Study.

They found that initially, pregnancy increases a woman’s breast cancer risk. This increase peaks around five years after her last pregnancy, and then gradually declines.

As Dr Minouk Schoemaker, one of the researchers who worked on the study at the ICR, explained: “Our large international study has provided further evidence that pregnancy increases women’s risk of breast cancer at first – although the overall rates in the younger age groups that we looked at was still low.

“The protective effect of pregnancy on breast cancer risk becomes apparent later on, with women having a lower risk of developing the disease from around 24 years after childbirth, depending on their age at first birth and the number of births.”

As the headlines showed, at its peak, women who have given birth are at an 80 per cent increased risk of developing breast cancer. That sounds like a massive number – but what does it mean in real terms?

The ICR's Division of Breast Cancer Research contains over 100 scientists and clinicians. A key priority for the division is to identify and characterise breast cancer susceptibility genes.

Background risk

It’s important to remember that the vast majority of breast cancers occur in older women – 80 per cent of cases occur in women aged over 50.

In younger women, the so-called ‘background risk’ of breast cancer – the risk all women in the entire population have, and that cannot be avoided – is very low.

So in women under 50, all other factors being equal, the 80 per cent increase linked to pregnancy boils down to a simple sum, if you would bear with me on the maths: very low risk times 1.8 equals…still very low.

The same applies to the difference between older and younger mums. The researchers split women into groups of women who had their first pregnancy when they were younger than 25, between 25-34, and 35-39 years of age.

They found that compared with women who had not had children, these women had a 6, 25 and 40 per cent increased risk of breast cancer, respectively – but again, with the background risk being relatively low at these ages, these increases don’t translate to a worryingly large effect.

At the later end of the spectrum – 24 years after a woman’s last pregnancy, the point at which pregnancy has become protective – the sum works out differently. As the background risk is higher once women are in their fifties, the protective effect linked to pregnancy in older women is larger than their increased risk in the short term.

Numerous other factors

Aside from pregnancy and the other childbirth-related factors analysed in the latest study, there are numerous other factors that play into women’s risk of breast cancer – from genetics – for example, carrying the BRCA1 or ‘Angelina Jolie’ gene is known to strongly raise the risk of breast cancer – to wide-ranging lifestyle and hormonal factors.

An individual woman’s overall breast cancer risk is influenced by all these various risk factors together, which each raise or lower her risk of developing the disease to a different extent.

So while the latest findings shouldn’t cause any sleepless nights, the link between pregnancy and other childbirth-related factors identified in the study are important for women and doctors to keep in mind.

And with each of these important epidemiological findings, scientists move one step closer to untangling the enormously complex question of breast cancer risk, allowing them to get better at calculating individual women’s risk, and opening up new avenues to study how and why they increase or decrease the risk of breast cancer.

“We do not yet know why pregnancy affects breast cancer risk”, Dr Schoemaker concluded, “but we hope our findings will help better predict individual women’s risk of breast cancer, and increase breast cancer awareness in young mothers.”