Women with high-risk, early-stage breast cancer who also have inherited faults in their BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes have shown a remarkable response to the targeted drug olaparib in a major clinical trial.

The OlympiA trial showed that adding olaparib for one year following standard treatment for patients who had an inherited BRCA mutation and early-stage, HER-2 negative breast cancer, cut the risk of their breast cancer returning by 42 per cent at a median 2.5-year follow-up.

The findings establish olaparib – already used to treat advanced ovarian and breast cancer – as the first drug that targets the specific biology of the BRCA genes to show success for treating early-stage breast cancer with an inherited BRCA mutation, potentially increasing the number of patients cured of their disease.

Potentially increasing cures

The findings also suggest that gene testing for inherited BRCA mutations should be more widely available for women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer to establish whether they could benefit from the targeted drug.

The trial – intended to follow patients for 10 years – showed a significant treatment effect at interim analysis at two and a half years and was therefore reported early.

The results have been made available at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting (Abstract LBA1, Plenary) and are simultaneously published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Major breakthrough

The international study, involving 671 study locations, was coordinated globally across multiple partners by the Breast International Group (BIG). Professor Andrew Tutt at the ICR and King’s College London was Chair of the Steering Committee for the OlympiA study, and was also involved in early laboratory research on PARP inhibitors such as olaparib, and their subsequent clinical development.

The Breast International Group coordinated the trial’s UK sites through the Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit at the ICR. Inherited mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes account for five per cent of all breast cancers. Women with early-stage breast cancer who have inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations are typically diagnosed at a younger age and often require more intensive treatment.

OlympiA trial researchers studied 1,836 women with HER-2 negative breast cancer, who also had a mutation in their BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes and had undergone standard treatment, including surgery, chemotherapy, hormonal therapies and radiotherapy, where appropriate. Patients were randomly allocated to receive either 300mg twice day of olaparib or a placebo for one year and were then followed up.

The trial has been reported at an early point because it showed clear results that could change practice, but the trial will continue.

At a median 2.5 years of follow-up, 85.9 per cent of patients on olaparib were alive and free of cancer versus 77.1 per cent who received a placebo – representing a 42 per cent overall drop in risk of cancer returning, new cancer developing or death.

Similarly, 87.5 per cent and 80.4 per cent of patients in the olaparib and placebo groups, respectively, were alive and free of disease which had spread to other parts of their body, representing an overall drop of 43 per cent in the risk of cancer developing distant metastases.

Olaparib was developed as a genetically targeted cancer treatment following landmark research in 2005 by ICR scientists. We are working to develop targeted treatments for all types of cancer. Please donate today to help us finish cancer.

A discovery decades in the making

Of patients in the trial, 82 per cent had triple-negative breast cancer, which can be particularly aggressive and difficult to treat.

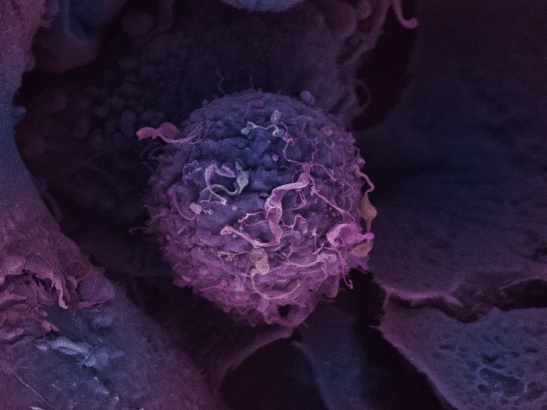

Olaparib works by stopping cancer cells from being able to repair their DNA by inhibiting a molecule called PARP and trapping it on DNA in a way that makes the cancer cells reliant on the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.

In cancers with faults in these genes, this causes cancer cells to die. That is why it works particularly well for patients with faulty versions of the BRCA genes – which are normally involved in another system for repairing DNA called homologous recombination.

Cancer cells cannot survive if they do not have functioning DNA repair through homologous recombination and if their PARP enzyme has been drugged and trapped on DNA.

Underpinned by work from ICR scientists

Olaparib was developed as a genetically targeted cancer treatment following landmark research in 2005 by UK scientists at the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at the ICR, funded by Breast Cancer Now and Cancer Research UK, which demonstrated that cancer cells with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations were very sensitive to PARP inhibitors.

The ICR also led on bringing PARP inhibitors to the clinic through phase I trials of olaparib – designed and led by ICR Professors Johann de Bono, Andrew Tutt and Stan Kaye at the ICR and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust – and found that olaparib was effective against tumours with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, and had fewer side effects than many traditional chemotherapies.

OlympiA is a collaborative study being coordinated worldwide by the Breast International group (BIG), in partnership with NRG Oncology, the US National Cancer Institute (NCI), Frontier Science & Technology Research Foundation (involving research staff in the US and in the affiliate office in Scotland), AstraZeneca and MSD. The trial is sponsored by NRG Oncology in the US and by AstraZeneca outside the US.

Increase chances that women will remain free of their cancer

OlympiA Steering Committee Chair Professor Andrew Tutt, Professor of Oncology at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and King’s College London, said:

“We are thrilled that our global academic and industry partnership in OlympiA has been able to help identify a possible new treatment option for women with early-stage breast cancer who have inherited mutations in their BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. Olaparib has the potential to be used as a follow-on to all the standard initial breast cancer treatments to reduce the rate of life-threatening recurrence and cancer spread for many patients identified through genetic testing to have mutations in these genes.

“The frequency of significant side effects in the study was relatively low. The new findings also show the need and value of testing for these inherited BRCA mutations in women with early-stage breast cancer to identify those who could potentially benefit from this new targeted approach.

“Women with early-stage breast cancer who have inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations are typically diagnosed at a younger age. Up to now, there has been no treatment that specifically targets the unique biology of these cancers to reduce the rate of recurrence, beyond initial treatment such as surgery, hormone treatment, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

“This major international study coordinated by the Breast International Group shows that giving olaparib for a year to patients with inherited BRCA mutations after they have completed initial treatment increases the chances that they will remain free of invasive or metastatic breastcancer.”

Science transforms lives

Professor Tutt is also Director of the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at the ICR, and of the Breast Cancer Now Research Unit at KCL. He added:

“The development of olaparib for cancer patients with mutations in their BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, and in other DNA repair genes, is a great example of collaborative research between academia, charities and industry, and between partners in the UK and across the world. It is also a perfect example of how scientific innovation can transform the lives of patients. I anticipate that olaparib will now go forward for assessment by global medicines regulators and hope it can become a new treatment option for some women with high-risk forms of early-stage breast cancer and inherited BRCA mutations.”

Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

“Olaparib was the first cancer drug in the world to target inherited genetic faults. It is also now the first targeted drug to have been shown to effectively treat patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and early-stage breast cancer, potentially curing some women of their disease. This is a major breakthrough.

“It’s fantastic that decades of ICR science into identifying cancer’s weaknesses – alongside academic, charity and industry partners in the UK and worldwide – has led to global trials which are now changing the outlook for patients. I am now keen to see this new treatment be approved and made available to patients in the UK and worldwide as fast as possible.

Groundbreaking trial

Professor Judith Bliss, Professor of Clinical Trials at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and Director of the ICR’s Cancer Research UK-funded Clinical Trials and Statistics, said:

“This an extremely important trial for a group of patients who are in urgent need of more targeted therapies to treat their cancer.

“It is fantastic that the ICR has been able play an important role in this worldwide initiative and that we’ve enabled patients in the UK to access this groundbreaking trial. It is a great example of how pioneering science can benefit patients through worldwide collaboration.”