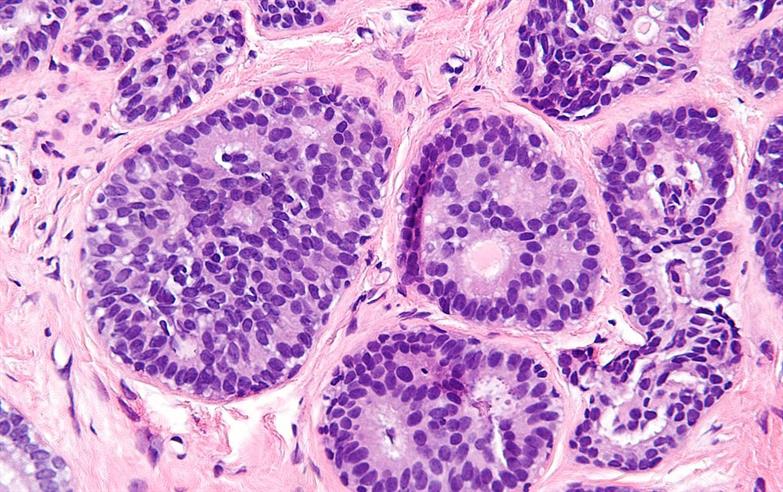

High magnification micrograph showing breast core biopsy of atypical ductal hyperplasia. Image credit: Copyright © 2011 Michael Bonert. Licence: CC BY-SA 3.0.

Clinicians should take multiple biopsies from patients in clinical trials of targeted breast cancer drugs to avoid missing key mutations with important implications for treatment, new research finds.

Genetic profiling of patients’ tumours using biopsies has become more common in recent years, helping to drive personalised therapy and ensure that patients receive the treatments most likely to be effective for them.

The study, funded by leading charity Breast Cancer Now and published today in the journal Nature Communications, found that analysing a further biopsy could catch key genetic mutations that may influence a patient’s response to aromatase inhibitor treatment.

Developing a more accurate picture of tumour mutations

Researchers in the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust found these mutations were likely to be missed in around a quarter of patients by investigations which rely on a single biopsy.

They concluded that researchers should take several biopsies to develop a more accurate picture of mutations within the tumour, and warned that previous studies which relied on only one biopsy should be treated with caution as they could have missed important mutations.

The study, led by Professor Mitch Dowsett and Dr Pascal Gellert, analysed samples from the POETIC trial (perioperative endocrine therapy - individualising care) — the largest pre-surgical study to date to identify what makes some patients respond well to aromatase inhibitors while others do not.

In POETIC, post-menopausal women with ER+ breast cancer received an aromatase inhibitor for a four-week period starting two weeks prior to standard surgery. Biopsies were collected at baseline and surgery, and a control group of patients were not given aromatase inhibitor treatment but still had two samples taken, which allowed genetic differences in repeat biopsies to be seen without any potential confounding effects of treatment.

Biopsies missing important mutations

Comparing the six most frequently mutated genes in paired baseline and surgery samples from 86 patients, the researchers found that the same mutations were present in both samples in 71% of cases, but at least one of the mutations was present in only one of the samples in 29% of patients. The control and treated groups were analysed separately, as well as together, revealing no difference in the variability of mutations between samples, and indicating that the short-term use of aromatase inhibitors had not influenced the comparisons.

The results reveal a significant group of patients for whom a single biopsy would have missed potentially important mutations — for example those which may predict how the tumour will respond to aromatase inhibitor treatment or others that could reveal weaknesses within the tumour that may render it sensitive to the addition of another drug.

The findings could be due to the high degree of spatial heterogeneity in mutations within a patient’s tumour, with different genetic information driving the cancer’s growth being found in different areas of the tumour.

Gene mutation involved in resistance to treatments

The research team also identified that mutations to a particular gene could be centrally involved in the resistance to aromatase inhibitor treatments used in oestrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer, such as anastrozole and letrozole.

ER+ tumours account for up to 80% of cases and aromatase inhibitors, which reduce the production of oestrogen, are the most effective means of treating this form of breast cancer in post-menopausal women. However these drugs are not effective for all patients and some can develop resistance to them.

Tumours which responded poorly to aromatase inhibitor treatment were found to have a greater number of mutations overall. In particular, a master regulator in the tumour cells called TP53 was mutated more in patients with poor response to aromatase inhibitors.

In the long-term, this research will help to find the best way of delivering personalised treatments based on the genetic profile of each patient’s tumour. To achieve this, doctors need to be able to reliably predict how an individual ER+ patient will respond to aromatase inhibitor treatment at diagnosis, which would ensure that patients only receive treatments that benefit them.

'Critical' that we use this information

Study leader Professor Mitch Dowsett, Professor of Biochemical Endocrinology at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and Head of the Ralph Lauren Centre for Breast Cancer Research at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, said: “Accurately identifying the mutations in cancers is critical to our understanding of the causes of cancer and to the development and targeting of new drugs more precisely to individual patients.

“Our work in patients with the most common form of breast cancer showed that to identify the mutations accurately in an individual’s tumour required more than one biopsy of the type usually used for diagnosis.

“It is critical that we take this information into account as we try to identify those patients most likely to respond to our new therapies.”

Providing 'more insight into drug resistance'

Baroness Delyth Morgan, Chief Executive at Breast Cancer Now, said: “This research looks at how some of the most common forms of breast cancer become resistant to treatments which are usually extremely effective.

“By taking more than one biopsy, which can reveal a wider range of genetic mutations, the researchers found an improved method which will in future give us more insight into drug resistance.

“This points the way to improve future research into personalised treatments, by capturing as much genetic diversity within patients’ tumours as possible.”

Breast Cancer Now is very grateful to Walk the Walk, The Eranda Foundation, and The Trustees of The Mary-Jean Mitchell Green Foundation for their exceptionally generous support of Professor Mitch Dowsett’s research.

The POETIC trial was funded by Cancer Research UK.