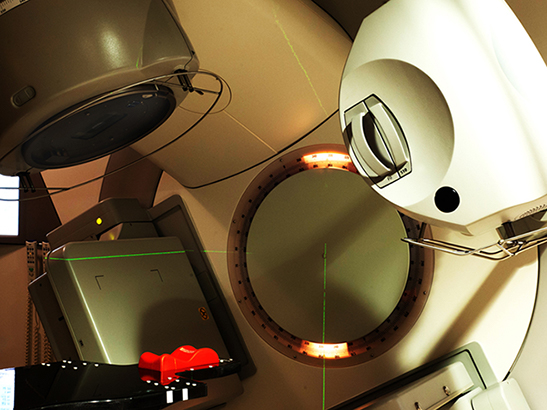

Radiotherapy IMRT machine. Credit: Jan Chlebik for the ICR.

Scientists have developed a new mathematical tool which will speed a smart new type of radiotherapy into the first patient trials.

Physicists from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and two German research centres developed an algorithm – a set of mathematical rules – to tackle a major current challenge in the development of microbeam radiation therapy, or MRT.

MRT uses high-energy X-ray beams narrower than a human hair to blast tumours with radiation while being gentle on healthy tissue, allowing the treatment to reach tumours where surgery is not possible – such as in the brain or lungs.

Although MRT could be used in future cancer treatment, current methods to plan the right doses of treatment can take computers days to process.

Big reductions in computation time

The researchers' algorithm, which they have published for the benefit of the wider research community, reduces the time a high-end PC takes to make these calculations from over 100 hours to just over three minutes.

The algorithm is an important step in ensuring treatment can be planned and delivered quickly, safely and accurately, and could help to treat the first patients with cancer using MRT in clinical trials.

It is already being used in treatment planning at the world's most powerful synchrotron, the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in France, a radiation machine that produces high-energy X-rays for scientific and medical purposes.

The study, published in the journal Physics in Medicine and Biology, was led by scientists from the ICR, the German Cancer Research Centre in Heidelberg and the University of Munich, with collaboration from researchers at the ESRF.

The ICR's MR Linac machine combines two technologies to tailor the shape of X-ray beams in real time and accurately deliver doses of radiation.

As accurate as 'Monte Carlo' simulations

Currently 'Monte Carlo' computer simulations provide treatment plans for MRT, but because each microbeam is extremely narrow, accurate plans take a long time to produce.

In the study, the scientists developed an algorithm to quickly estimate the dose delivered by microbeams to tumour tissue and surrounding areas, and compared the calculated values to the computer simulations.

The algorithm took just a few minutes of computer processing time and gave similar results compared with computationally intensive Monte Carlo simulations. It gave accurate results when used in treatment planning for mice, and for a 'phantom' model of a human head.

Lead author of the study Dr Stefan Bartzsch, a Post-Doctoral Training Fellow in the ICR's Radiotherapy Physics Modelling team, said:

“Our algorithm can calculate dose distributions in treatment planning in minutes, and is as accurate as the computer simulations generally used to calculate doses which can take more than 100 hours, even on high-end computers.

“It has already been incorporated into treatment planning systems for more testing, and we hope it will bring forward the treatment of patients with microbeam radiation therapy through the first clinical trials of this pioneering technology.”