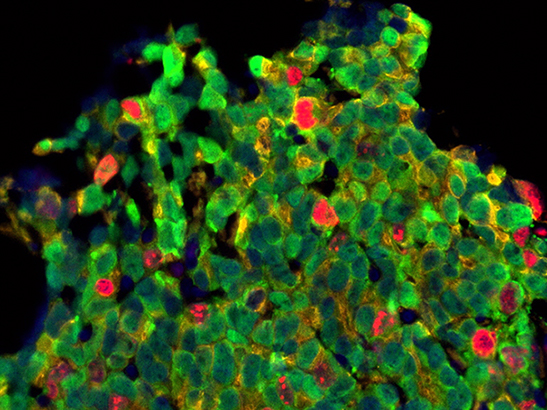

Prostate cancer cells. Credit: Mateus Crespo, Ana Ferreira, Daniel Nava Rodrigues and Johann de Bono

Our wide-ranging programme of prostate cancer research has delivered new targeted cancer drugs, radiotherapy regimens, genetic discoveries and diagnostic blood tests.

Together these have had huge benefits for patients – helping men to live longer, improving their quality of life and increasing cure rates.

Here are some of our most exciting research advances in prostate cancer – improving treatment for men today, and heralding a brighter future for tomorrow’s patients.

ICR at the forefront of precision medicine

We’ve long been at the forefront of precision cancer medicine, which gives individual patients the best treatments according to the genetic profile of their cancer.

In the past two decades a new wave of targeted drugs has extended life by blocking vulnerabilities in specific types of cancer – including abiraterone, which was discovered at the ICR and is now a routine treatment for advanced prostate cancer.

Professor Johann de Bono is a world-famous prostate cancer scientist and leader of numerous trials of new prostate cancer drugs.

“It’s a tremendously exciting and inspiring time to be a researcher in our field,” says Professor de Bono, who leads a team of researchers at the ICR and our partner hospital, The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust.

“Our biggest achievements include the discovery of abiraterone and the successful clinical trials that led to it being used worldwide to extend the lives of hundreds of thousands of men. We are also proud to have been involved in trials of several other drugs, including enzalutimade, cabazitaxel and radium-223, which have been used globally in prostate cancer treatment.”

Matching patients to treatments

Trials have become ever more precise – with patients now routinely matched to treatments with the best possible chance of success. One standout example is the drug olaparib, the development of which was underpinned by our research and which was approved by the NHS last year for women with a type of ovarian cancer.

Trials led by Professor de Bono’s team have now shown that olaparib could work in prostate cancer, for men whose tumours have mutations in specific genes.

Professor de Bono says: “Men on trials at our unit generally live twice as long with advanced cancer as they did in the early 2000s. By spotting when a cancer is progressing and having a range of trials to choose from, average survival has gone from around two to around four years – with some men living a decade or more.”

We are training the next generation of researchers; by supporting a PhD studentship, you could help us advance personalised prostate cancer treatment.

Liquid biopsies – quicker, simpler and less invasive

The need to match patients to the most suitable trials of the best treatments has been one of the drivers of a new revolution in clinical research – a revolution with our scientists a global driving force.

Dr Gerhardt Attard, one of our Team Leaders, who also works in the Drug Development Unit with The Royal Marsden explains:

“We’ve known for a long time that not all cancers are the same, and some respond better or worse to treatment. The challenge is to spot much sooner when a treatment is not working, so we can stop it and move patients on to something else that is more likely to work.”

Dr Attard has led the development of a new type of blood test – called a liquid biopsy – that stays one step ahead of evolving prostate cancer as it mutates into a more aggressive form. This test analyses cancer DNA circulating in the blood to determine whether the drug abiraterone is still working – and flags to doctors when a patient will benefit more from another therapy.

Dr Attard says: “Liquid biopsies are quicker, simpler and less invasive than traditional biopsies and scans. They are also potentially more accurate, because they can pick up DNA from multiple tumours throughout the body and give a comprehensive picture of cancer genetics. In the future, I aim for it to become routine to use these tests to track tumour mutations and make faster decisions.”

Big ideas for prostate cancer treatment

Precision drugs and liquid biopsies are already used to treat prostate cancer, whether as NHS treatments or in research studies. But our researchers also have other big ideas that could fundamentally alter how prostate cancer is treated in the future.

Professor David Dearnaley led the recent CHHiP trial, which showed that fewer, larger doses of radiotherapy are just as effective as the standard regime, sparing patients the inconvenience of unnecessary hospital appointments. When delivered using precision radiotherapy the new regime also reduces the rate of side-effects.

He explains: “A lot of our research is focused on reducing the side-effects of treatment. Radiotherapy effectively cures a lot of our patients, but often at the cost of some long-term side effects – of which bowel problems are one of the most common and limiting to quality of life.”

Individualising radiotherapy for patients

One of the most intriguing ideas his team is looking at is the impact of gut bacteria on treatment side-effects.

X-rays kill many of the ‘good bacteria’ in the gut that help with digestion, which means that men treated for prostate cancer often experience significant symptoms and struggle to digest foods they could before.

Professor Dearnaley says: “In the future, we want to take faecal samples from men before treatment, and use genetic profiling of their gut bacteria to repopulate their digestive systems with the right mix.

“We’ve already identified several main types of bacterial populations in patients – which we call enterotypes – and ultimately we aim to use this information to improve treatment.

“We’re also taking genetic profiles of men with prostate cancer and then following them for a long time – 10, 15 years or more – to see if we can find clues in their genes that could help us work out who will develop some of the longer-term side-effects of radiotherapy.

“We want to link these changes with the detailed biophysics of treatments given using Big Data methods and find out if we can individualise radiotherapy for patients.”

Pioneering brand new genetic approaches

Professor Ros Eeles also carries out genetic profiling of men with prostate cancer – but on an even bigger scale. As a leader of several international research groups – including hundreds of researchers at universities worldwide – her team analyses DNA from hundreds of thousands of men with and without prostate cancer to try to find genetic clues about the disease.

Professor Eeles says: “We’ve found around 100 genetic factors that influence a man’s chance of developing prostate cancer, or developing a more aggressive form. These DNA coding differences give researchers clues to follow that will illuminate the disease’s biology, and could lead to new treatments.”

“In the future, we also want to see tests for these genetic differences being used to predict the risk a cancer will develop or progress. We believe we are at the point now where these tests will give useful information to doctors in addition to existing measures of risk – the challenge is in finding how to bring this technology into the NHS, at an affordable cost.”

Our researchers have long been at the forefront of prostate cancer research.

They are still leading in some of our traditional areas of strength – like drug discovery and radiotherapy – and are also now pioneering brand new approaches that could transform prostate cancer treatment.