A new study has provided novel insights into the effects of radiation on the immune cells surrounding breast cancer tumours. The findings show that the relationship between these cells, known as the tumour-immune microenvironment (TIME), and radiation is more complex than previously believed. This means further work is necessary to determine how best to use radiotherapy to maximise the benefits of other treatments, such as immunotherapy.

For the first time, the researchers assessed this relationship in the pre-operative setting with doses that are routinely used in the post-operative setting. Here, the tumour is still in place in the body, so the effects of radiotherapy on the TIME surrounding it can be determined more clearly.

The study findings are likely to have important clinical implications, particularly in relation to the design of future radiotherapy clinical trials. In the longer-term, the team believes that this work could lead to more successful combination therapies involving radiotherapy and immunotherapy, which could improve outcomes in high-risk breast cancer patients.

The study was led by scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and published in the journal International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. The work was funded by The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR), which is both a research institute and a charity.

Using neoadjuvant radiotherapy to boost treatment

There is increasing interest in the potential of radiotherapy to prime a patient’s body for treatment by making their cancer more receptive to immunotherapy – a type of treatment that recruits the body’s immune system to fight the disease.

Other research has suggested that radiotherapy may be able to switch so-called ‘cold’ tumours, which are resistant to immunotherapy and must be treated with traditional therapies such as chemotherapy, to ‘hot’ tumours.

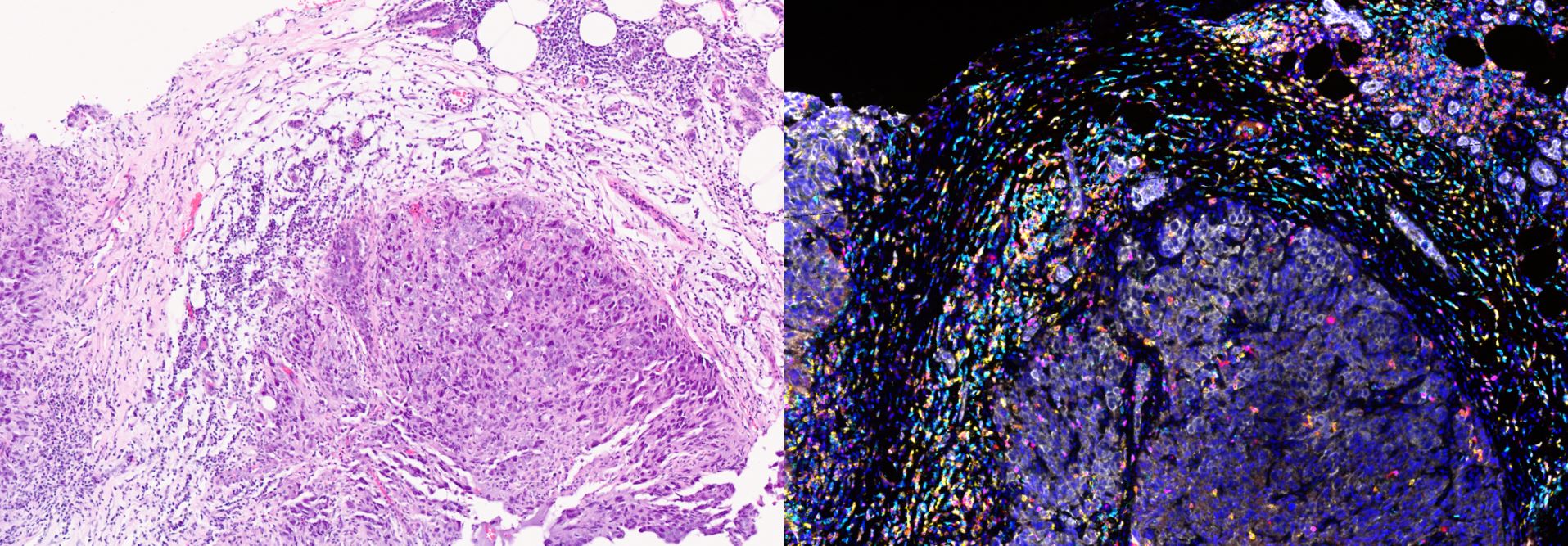

Scientists can distinguish between the two types by looking for cancer-fighting white blood cells, or lymphocytes, called T-cells. ‘Hot’ tumours have been infiltrated by T-cells, which is a sign that the immune system has recognised the cancerous cells and is working to destroy them. Scientists refer to these cells as tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and use them as a marker of survival in several types of cancer.

There is evidence to suggest that radiotherapy can increase the number of TILs in tumours. As a result, it is widely believed that neoadjuvant radiotherapy (NART), which is delivered before surgery with the tumour still present, could increase the likelihood of a positive outcome using immunotherapy.

However, some preclinical studies have found that radiotherapy may in fact suppress the body’s immune response, which would make immunotherapy less effective. The researchers behind the current study aimed to solve this conundrum.

Harnessing data from clinical trials

Previous research has been limited by the current standard of care in breast cancer, whereby radiotherapy is routinely delivered to a patient following surgery to remove their tumour. This approach has meant that researchers have only been able to study the effects of irradiating the cancerous cells in a laboratory setting, where the TIME cannot be considered.

For this study, the research team used patient samples from two UK-based clinical trials investigating NART in people with breast cancer. The first trial, Primary Radiotherapy And DIEP flAp Reconstruction Trial (PRADA), was led by The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and partially funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research’s (NIHR’s) Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and the ICR. The charity Breast Cancer Now, which also funds the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at the ICR, funded the second clinical trial, Neo-RT, which was led by Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

These trials provided the researchers with blood and tumour samples from a total of 43 people with non-metastatic breast cancer of various subtypes. The samples were taken at multiple timepoints throughout the trials, allowing the researchers to detect any differences between the pre-, during, and post-radiotherapy samples.

NART may significantly deplete white blood cells

The researchers began by allocating scores to the patient samples based on the number of TILs located in certain regions of the tissue. They noted that higher scores correlated with specific breast cancer subtypes, with people with HER2-positive or triple negative breast cancer more likely to have increased lymphocyte infiltration. People with higher grades of breast cancer also typically had higher scores.

When they looked at changes to these scores over time, the researchers noted that NART seemed to contribute to the sustained loss of TILs from both the TIME in the breast and the peripheral bloodstream. Importantly, the levels of these cells did not recover by the time of surgery.

The study authors draw particular attention to the routine delivery of radiotherapy to the regional lymph nodes in people with breast cancer, which is done to prevent the disease from spreading further. They note that this strategy may be impairing immune activity and suggest that “preserving the lymph nodes may prove crucial for the effective combination and sequencing of radiotherapy with immune checkpoint blockade [a form of immunotherapy] prior to surgery.”

“A unique opportunity”

Joint senior author Dr Navita Somaiah, Group Leader of the Translational Breast Radiobiology Group at the ICR and Honorary Consultant Clinical Oncologist in the Breast Unit at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, said:

“Our study represents a major advance in our understanding of the dynamics of TILs in response to radiotherapy in breast cancer. Despite the explosion of interest in the immunogenic potential of radiotherapy, a huge gap has persisted in our knowledge about the effect of radiation alone on the breast TIME.

“This work has started to close that gap, but it also highlights the need for deeper interrogation of factors such as dose fractionation, the timing of radiotherapy and volumes irradiated so that we can optimise radiation-induced immunogenic cell death.”

Joint first author Miki Yoneyama, a PhD student in the Translational Breast Radiobiology Group at the ICR, said:

“The recent trials testing the safety of NART in breast cancer gave us a unique opportunity to test the effects of radiotherapy in vivo. Our dataset represents a unique insight into the relationship between radiation and TIME, and it brings into question the widely held belief that radiotherapy converts immunologically ‘cold’ tumours into ‘hot’ tumours.

“Our findings will likely contribute to the ongoing debate about the merits of lymph node irradiation for patients receiving immunotherapies. We hope that further exploration of this complex area of radiobiology will ultimately lead to improved outcomes for everyone living with breast cancer.”

Image: Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes, a key type of immune cell, can be identified within the breast tumour microenvironment (left panel). Additional techniques allow researchers to study these in more detail, as shown in the right panel (white marks breast cancer cells, with other colours marking different types of lymphocytes). Credit: Miki Yoneyama and the Integrated Pathology Unit