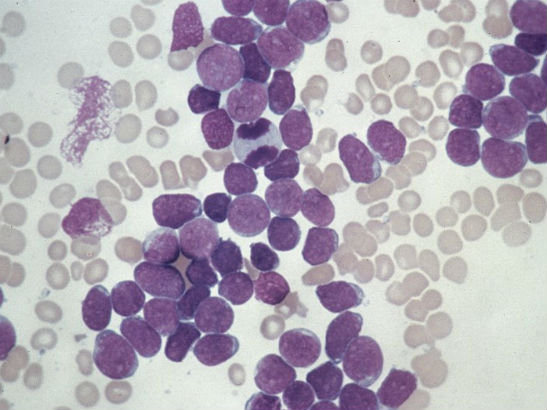

Image: Lymphoblastosis in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Author: Prof. Osaro Erhabor via WikiCommons. Credit: Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0

As one of the world’s most eminent cancer scientists, Professor Sir Mel Greaves has had a huge influence on our understanding of leukaemia. Since joining the ICR in 1984, he has built his career on viewing the disease – and cancer more broadly – through the lens of evolutionary biology. In recognition of this he was recently knighted for his services to childhood leukaemia research.

A defining moment for Professor Greaves came some 40 years ago when a visit to a children’s ward inspired him to devote his career to cancer.

At the time, little was known about childhood leukaemia. The same chemotherapies would cure some children but fail in others – with doctors unable to predict whether or not a treatment was likely to be successful.

So Professor Greaves began his work into the biology of childhood leukaemia in the hope of improving the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. He also became interested in how his research could lead to ways of preventing children from developing leukaemia.

Professor Mel Greaves has been knighted in the New Year Honours List for his pioneering and hugely influential research into childhood leukaemia.

Understanding leukaemia’s origins

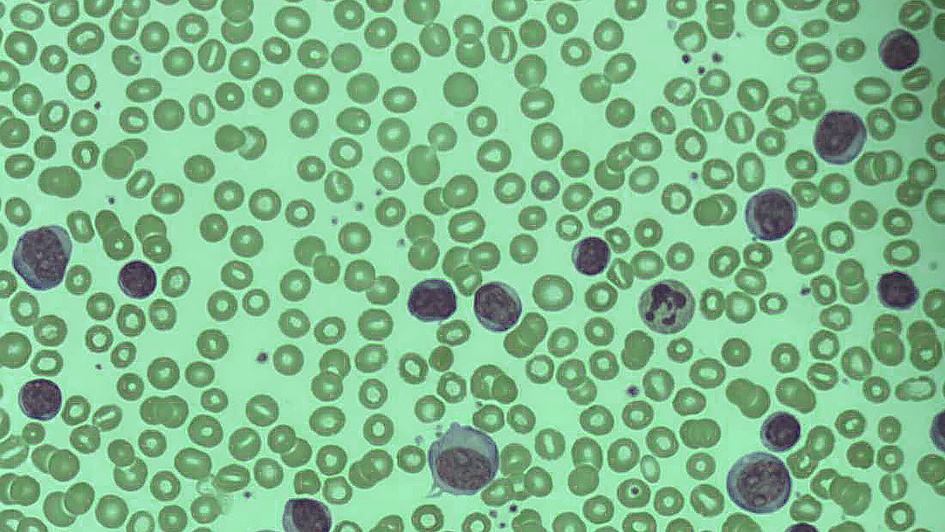

It was already known that leukaemia was a disease of white blood cells, which help police our bodies for threats as part of our immune system.

But Professor Greaves became the first to use methods inspired by immunology to separate childhood leukaemia into subtypes, based on the type of cell involved.

By studying cancer cells’ identity with antibodies made in his laboratory, Professor Greaves made it clear that the cellular origin of a child’s cancer – part of its evolutionary history – had a significant effect on its response to treatment.

Concentrating his efforts on acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), the most common type in children, Professor Greaves established an international consortium for classifying different forms of the disease.

Before long, his work led to doctors treating the different subtypes of ALL in more sophisticated or selective ways, and kick-started other scientific efforts that have led to the more detailed understanding of leukaemia we have today.

Causes and evolution

By this time Professor Greaves had already made an enormous difference to the lives of children across the world. But a slight shift in direction, inspired by his earlier studies, further transformed our understanding of leukaemia – and has even made an impact on our understanding of cancer itself.

During his research, Professor Greaves had spotted that the major subtype of ALL, called common ALL, had a marked incidence peak at two to five years of age, and was more common in developed countries. This provided a strong clue to its causation that he decided to follow.

By looking at differences between identical twins, who have the same inherited DNA, he went on to realise that two distinct events drive the development of the disease.

First, particular white blood cells have initial mutations that arise in the womb but only rarely lead to leukaemia, and then second ‘mutational events’ occur after birth that prime a child to later develop the disease.

ALL, Professor Greaves saw, evolves in response to the environment around it. Its development follows the rules of evolution as laid down by Charles Darwin: the survival of the fittest, with aggressive cancer cells emerging only if the environment is ‘right’ or supportive.

Centre for Evolution and Cancer

Professor Greaves went on to apply his evolutionary theories to cancers more generally, asking big questions about how treatments could be used to control the disease by influencing the path of evolution.

He has become a leading figure in the study of cancer evolution, consistently pushing colleagues across the world to appreciate the evolutionary nature of the disease and ultimately establishing the Centre for Evolution and Cancer at the ICR.

This Centre is one of very few across the world devoted to the study of cancer evolution, and holds great promise for discovering a new wave of drugs that might target the fundamental processes that drive cancer evolution, or even control the evolution of cancers to favour the less aggressive cells in a tumour.

Our latest research shows that within the next decade, we can make acute lymphoblastic leukaemia preventable. Your support will help us make this disease a thing of the past.

Clean childhoods

Meanwhile, Professor Greaves has continued to lead research into his first passion, saving the lives of children with leukaemia.

In a landmark paper published in 2018, compiling decades of genetic, immunological and epidemiological research, Professor Greaves strongly suggests that the second mutational step – a genetic change in a pre-cancerous cell that makes it cancerous – comes in the form of exposure to one or more common infections of childhood, like the flu.

However, this only happens in children who acquired the first mutation before birth and, in the very first year of life, have a deficit of exposure to benign or beneficial bacteria that prime the new born immune system. Infants who have minimal social contacts with older siblings or other children or who are not breast fed are, for example, more at risk of ALL.

It’s a revolutionary insight into the causes of leukaemia that could have far-reaching public health impact.

Professor Greaves explains: “This body of research is a culmination of decades of work, and at last provides a credible explanation for how the major type of childhood leukaemia develops.

“It strongly suggests that ALL has a clear biological cause, and is triggered by a variety of infections in predisposed children whose immune systems have not been primed.”

Public health

The most important implication of his latest research, Professor Greaves says, is that most cases of childhood leukaemia are likely to be preventable. It also busts some persistent, damaging but unsubstantiated myths about the causes of leukaemia, like that the disease is caused by exposure to electro-magnetic waves or pollution.

ALL might be prevented, says Professor Greaves, with simple and safe interventions to expose infants to a variety of common and harmless, but beneficial, bugs. It might even be prevented by specific oral probiotics.

But Professor Greaves cautions: “Before we get to public health initiatives, we need to test this prevention strategy in a model system of childhood leukaemia.”

He is now planning research in mice to work out how it might, in the future, be prevented in children, sparing them and their families the trauma of a diagnosis of ALL.

Professor Greaves’s career has had a great impact on our understanding of childhood leukaemia, as well as pioneering new ways of thinking about cancer in a broader sense.

“It’s been tremendously gratifying to help unravel the fundamental and genetic biology of leukaemia over the past 40 years,” says Professor Greaves, as he reflects on his career so far.

“I hope that our research will continue to have a real impact on children, by helping us to develop kinder, more effective treatments – and, potentially, by preventing many cases of childhood leukaemia altogether.”