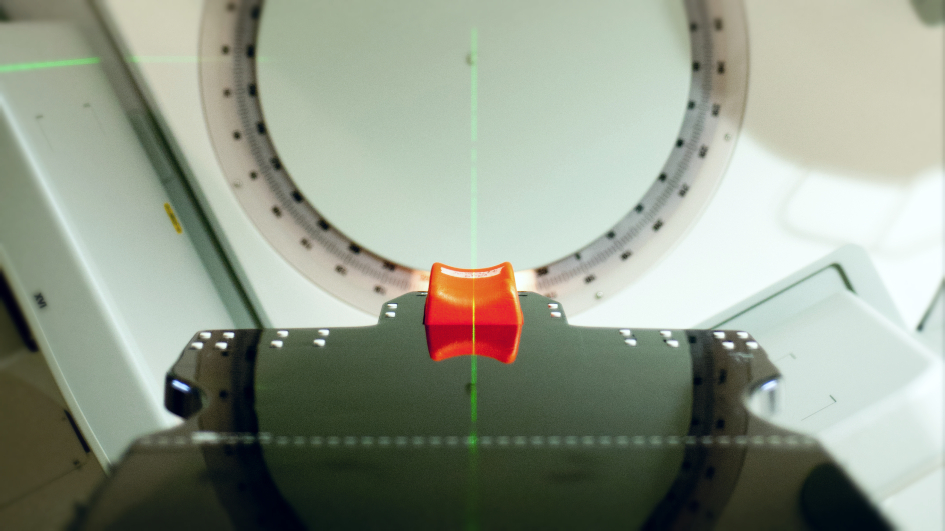

Image: Radiotherapy machine at The Royal Marsden Hospital. Credit: Jan Chlebik, The ICR

A major clinical trial has shown that changing the way radiotherapy is delivered could significantly reduce the side effects associated with radiotherapy treatment for prostate cancer.

Two new studies, led by researchers at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, show promise when it comes to reducing the risk of erectile dysfunction post-treatment, as well as reducing bowel symptoms such as rectal bleeding and increased bowel frequency.

Both pieces of work, funded by Cancer Research UK, are based on a landmark phase III clinical trial for prostate cancer – known as CHHiP – comparing conventional radiotherapy with hypofractionated high dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy.

The trial’s Chief Investigator is Professor David Dearnaley, Professor of Uro-Oncology at the Institute of Cancer Research and Consultant Clinical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden, and it is led by Professor Emma Hall’s team at the Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit at the Institute of Cancer Research.

Reducing the chance of side effects

The first of the two complementary studies, led by Dr Julia Murray at the Royal Marsden NHS Trust and the ICR’s Division of Radiotherapy and Imaging, evaluated data from the trial and sought to assess whether a relationship exists between reducing the volume of tissue treated with radiotherapy, the dose of radiotherapy delivered to the penile bulb, and the development of erectile dysfunction after treatment.

The study, published in the journal Clinical & Translational Radiation Oncology assessed a total of 276 men recruited to the CHHiP trial who were additionally randomised to receive image-guided radiotherapy, and followed up after treatment to assess the incidence of erectile dysfunction. Evaluation was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and the ICR.

Scientists were able to show that image-guided radiotherapy – which uses scans and x-rays to help doctors carefully plan treatment – can be used to reduce the total area of tissue which gets subjected to the radiotherapy, which in turn reduced the chance of side effects.

They were able to show that reducing the area to be treated still allows effective disease control, and that it’s possible to reduce the total dose delivered to the penile bulb by a significant amount.

Professor David Dearnaley said:

“Although this is a small study, the results are very promising. We have been able to show that the dose delivered to the penile bulb is related to erectile dysfunction, and by reducing treatment margins we could reduce the dose down to a level that we expect will be associated with reduced incidence of erectile dysfunction.

“There are excellent treatment options available for prostate cancer, but many patients live with disability after these treatments. Research focused on minimising side effects and long-term damage is critical to ensure that patients survive their cancers and have a good quality of life after treatment ends.

“Future work in this area may mean we can re-think the margins of treatment for prostate cancer, and reduce erectile dysfunction for many men after treatment.”

Smaller doses over a shorter time frame

Another study, published in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics focused on investigating and minimising the negative effects of radiotherapy on the bowel.

Some patients receiving treatment for prostate cancer report side effects such as rectal bleeding, faecal incontinence and an increase in bowel movements.

The CHHiP trial showed that a change in the way radiotherapy is delivered – giving smaller doses over a shorter time frame as compared to standard care – gave the same benefits as the standard treatment but is more convenient for men and considerably less expensive.

The patients in CHHiP had significantly reduced side effects compared to older studies using a similar dose because of the more advanced radiotherapy techniques used to treat men recruited to CHHiP.

This new study, led by Dr Anna Wilkins, Clinical Research Fellow in the Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit, showed that it’s possible to rein in the treatment constraints even further, to achieve the same disease management with even fewer side effects.

The work has recommended new dose levels which should be achievable in routine practice, and the team expect clinical practice to change around the world.

This is the first time such dose constraints have been produced for the shorter, four-week radiotherapy schedule designed in the CHHiP trial.

We are now poised to outsmart cancer with the world’s first anti-evolution 'Darwinian' drug discovery programme, in which we will focus on understanding, anticipating and overcoming cancer evolution, and preventing drug resistance.

'Changing the standards of care'

Dr Wilkins said:

“We are really pleased to be able to show that stricter dose constraints than those used in CHHiP may further reduce bowel symptoms for patients post-radiotherapy.

“Patients who complete treatment for prostate cancer go on to live cancer-free for many years, but may have to live with symptoms caused by treatment which can be difficult to manage and lower quality of life.

“Changing the standards of care to reduce side effects even further, while maximising the effect of treatment, is important.”

Chris, 77, from Cheltenham, was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2016 after attending a PSA test offered by his local prostate cancer support group. Because the tumour was close to the edge of the prostate, he was advised that surgery might be too risky and instead, a course of radiotherapy was recommended to treat his cancer.

“I had daily sessions of radiotherapy for seven weeks,” said Chris. “I was fortunate to experience only minimal side effects at the time – but, shortly after the treatment finished, I began to have problems with my bowels which over a few weeks gradually got worse.

“Although I’ve been cancer-free for two years, I still suffer quite badly from the delayed after effects of radiotherapy. These include anal bleeding and faecal leakage together with an urgent need to go to the toilet: sometimes three times in a day.

“This is manageable but it does have quite a significant impact on my life as the unpredictability means I don’t always have the freedom to do what I want. I worry if I am going to be more than 15 minutes away from a toilet.

“My consultants advise that these problems are likely to be permanent. If there’s a way to deliver radiotherapy with the same success, but without the after effects, this will make a massive difference to the quality of life of many men in the future.”