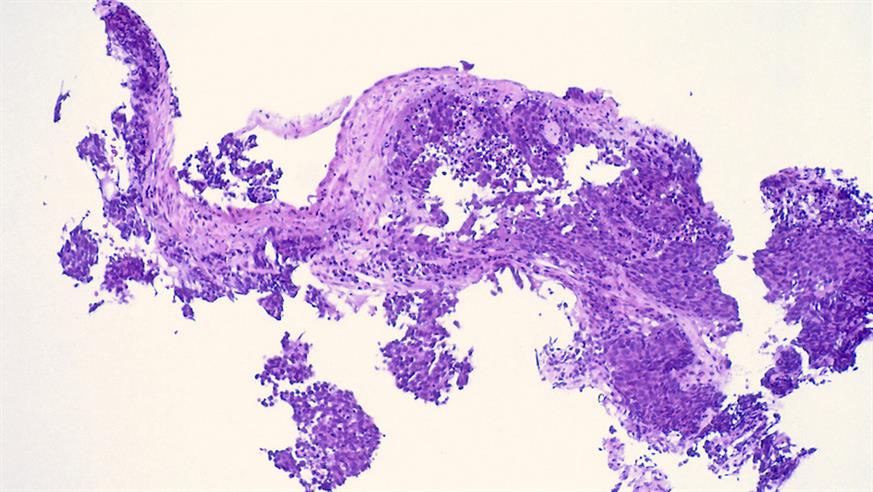

Small cell carcinoma. Bronchial biopsy specimen.Credit Yale Rosen. Licensed under a Creative Commons BY-SA 2.0 license.

A class of drugs used to treat certain breast cancers could help to tackle lung cancers that have become resistant to targeted therapies, suggests a new study in mice from the Francis Crick Institute and The Institute of Cancer Research, London.

The research, published in Cell Reports, found that lung tumours in mice caused by mutations in a gene called EGFR shrunk significantly when a protein called p110α was blocked.

Drugs to block p110α are currently showing promise in clinical trials against certain breast cancers, so could be approved for clinical use in the near future. The new findings suggest that these drugs could potentially benefit patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers whose tumours have become resistant to treatment.

Professor Julian Downward's Lung Cancer Group is unravelling the molecular mechanisms by which oncogenes drive tumour formation, growth and spread, with particular focus on the RAS oncogenes and on the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).

“At the moment, patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers are given targeted treatments that are very effective for the first few years,” explains study leader Professor Julian Downward, who has labs at the Crick and the ICR. “These drugs are improving, but unfortunately after a couple of years the cancer usually becomes resistant and starts to grow and spread again. The second line of treatment is currently conventional chemotherapy, which is not targeted and has substantial side-effects.

“Our new study suggests that it would be worth investigating whether p110α inhibitors could be used as a second-line therapy. As our research is at such an early stage, more research in mice and patient cells would be needed before even considering clinical trials, but it opens up a promising avenue of investigation.”

Very few side-effects

For this research, the team targeted a specific interaction between the RAS protein and p110α. The RAS gene is mutated in around one in five cancers, causing uncontrolled growth, and is a key focus of Julian’s research. When they blocked this interaction in genetically modified mice with EGFR mutations, their tumours shrank significantly.

Before the intervention, the tumours filled around two thirds of the space inside the lung. When the interaction between RAS and p110α was genetically blocked, this shrank significantly to about a tenth of the space inside the lung. The intervention also had very few side-effects.

“As we wanted to pinpoint the specific interaction responsible, we used a genetic technique that would not be practical in a patient treatment,” says Julian. “We’re looking to develop ways to do this with drugs, as blocking this specific pathway would significantly reduce side-effects, but this work is many years from the clinic. In the medium-term, investigating existing drugs that inhibit p110α will be the next step. While these have side-effects, including temporary diabetes-like symptoms during treatment, they are still less toxic than chemotherapy.”

-547x410.jpg?sfvrsn=c727183b_2)