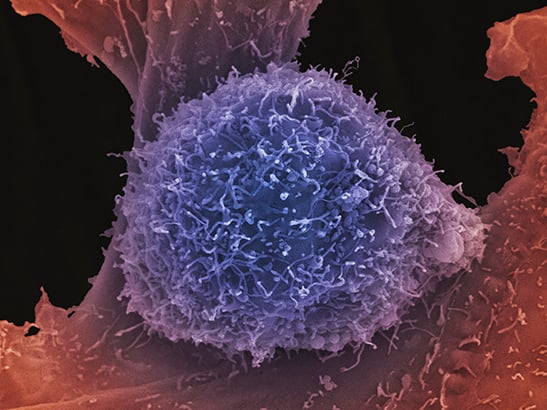

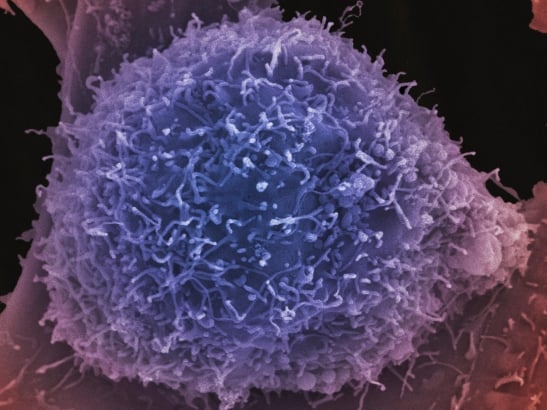

Image: A scanning electron microscope image of a prostate cancer cell. Credit: Anne Weston, Francis Crick Institute. CC BY-NC 4.0.

At The Institute of Cancer Research, London, we often refer to abiraterone as one of our greatest success stories. Discovered in one of our labs around 30 years ago, abiraterone has now become a standard of care for advanced prostate cancer, benefiting hundreds of thousands of men worldwide.

Turning a promising chemical into a safe drug that can benefit patients is no easy feat – but that is precisely what our researchers were able to achieve.

Their efforts led NICE to recommend the drug back in 2012, when it was made available to men with aggressive forms of prostate cancer on the NHS for the first time. Today, the drug is a mainstay in the treatment of prostate cancer – but the journey, which started in the 1990s, wasn't without its obstacles.

The discovery and development of abiraterone

It all started with a team based in what is now the ICR’s Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery. The team, involving Professor Mike Jarman, Dr Elaine Barrie and Professor Gerry Potter, as well as many other collaborators including Professor Stephen Neidle and Dr Charles Laughton, set out to design drugs to block CYP17, an enzyme that helps produce male sex hormones. Their hope was to use the drug to directly disrupt testosterone production, which fuels prostate cancer.

The team initially developed a chemical called CB7598, which then became abiraterone acetate. This chemical was able to successfully block CYP17 in cells in the lab and in animals with cancer, and the team eventually managed to turn it into a drug suitable for use in humans.

Despite the initial promise of the drug, things took an unexpected turn. At the time, how hormones fuelled prostate cancer was still a bit of a mystery. Researchers did not fully understand the mechanism behind prostate cancer’s reliance on testosterone, and some were concerned about the possible side effects of abiraterone – such as a life-threatening condition known as adrenal insufficiency, which occurs when the adrenal glands do not produce enough hormones.

This lack of understanding and concerns around the safety of abiraterone led the pharmaceutical company involved, Boehringer Ingelheim, to withdraw from developing the drug – and abiraterone was shelved for a few years.

But in 2003, when Professor Johann de Bono joined the ICR, he took an interest in abiraterone and challenged those who believed it couldn't work – insisting that drugs designed to block hormone production directly could be used to treat prostate cancer effectively.

Professor Johann de Bono is Regius Professor of Cancer Research at the ICR and Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden. He recalls:

“The reason for the lack of interest in abiraterone back then was that people believed advanced prostate cancers – cancers which had returned after initial hormone therapy – no longer relied on hormones to grow. So how would abiraterone, a hormone-blocker, help treat prostate cancer if the cancer no longer relies on said hormones? But in fact, as we found out later, advanced prostate cancer still relies on testosterone to grow – it even starts producing its own testosterone to fuel itself, becoming addicted to it.

“This new understanding meant that drugs like abiraterone, designed to directly block hormone production instead of just the testosterone produced by the testicles, were suddenly very promising.

“I also challenged the concerns around the safety of the drug, reasoning that adrenal insufficiency would not be an issue with abiraterone, as children born with an inherited deficiency of CYP17 do not suffer from the condition.”

How does abiraterone work?

Hormones are chemical messengers which coordinate different functions in our bodies including growth and development, metabolism, and mood. Testosterone is a hormone made mainly in the testes, but small amounts also come from the adrenal glands. Testosterone doesn’t usually cause problems but, in prostate cancer, it can make the cancerous cells grow faster.

Hormone therapy, also called Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT), is one of the most common ways to treat prostate cancers. The goal of this treatment is to reduce the levels of testosterone in the body or to stop testosterone from reaching the cancer cells.

Standard hormone treatments for prostate cancer block testosterone production in the testes, helping reduce the blood levels of testosterone. However, after a while, some patients stop responding to the standard hormone treatments and develop the more aggressive ‘castration-resistant’ form of the disease. One of the major reasons for this progression is production of testosterone by the tumour itself. In addition, other tissues, such as the adrenal glands, continue to make testosterone. Even though these cells only produce small quantities of testosterone, it can be enough to support the growth of some prostate cancers.

Abiraterone is a type of hormone therapy used to treat men with advanced prostate cancer, where the cancer has spread to other parts of the body. It works by inhibiting the production of testosterone in all tissues throughout the body, including in the tumour. It does this by irreversibly blocking CYP17 - the main enzyme involved in testosterone synthesis. CYP17 is involved in making the precursors of testosterone. Therefore, inhibition of CYP17 can completely block the production of testosterone and prevent the subsequent promotion of prostate cancer.

Indeed, early experimental studies in cancer cells and animal models showed that use of abiraterone can reduce the levels of testosterone and consequently, the size of testosterone-dependent organs. Through inhibiting all pathways involved in testosterone production, abiraterone has the potential to treat patients with the more aggressive form of prostate cancer.

STAMPEDE and its ‘practice-changing’ results

The Cancer Research UK-funded STAMPEDE clinical trial, which is coordinated by the MRC Clinical Trials Unit at University College London (UCL), is exploring the best ways to treat newly diagnosed advanced prostate cancer.

Rather than focusing on only one treatment, it’s made up of numerous trials that are investigating several different options. Running since 2005, each part of STAMPEDE compares a new treatment against the current standard hormone treatment for prostate cancer.

Abiraterone is one of its success stories — two trials within STAMPEDE have focused on the drug, with both showing very positive results.

In the first abiraterone trial, which was published in 2017, men who were starting standard hormone therapy for prostate cancer for the first time were given abiraterone alongside it. Participants were also given a steroid, prednisolone, that reduced abiraterone’s side effects. They took abiraterone four times a day and were given a hormone injection every eight weeks.

In the second trial, published in 2021 and led by the ICR and UCL, patients were once again given abiraterone alongside the standard hormone therapy, but some were also given a second prostate cancer drug, enzalutamide. This trial specifically looked at cases where the cancer had not yet spread to other parts of the body but had a high chance of doing so.

Whilst adding enzalutamide showed little effect, in both studies abiraterone showed major benefits. Patients who took abiraterone not only lived longer, but it also took longer for their symptoms to re-emerge. The second study also showed, after following participants for six years, that the cancer was less likely to spread in those taking abiraterone.

Abiraterone is already used to treat advanced prostate cancer in cases where it has spread to other parts of the body or has stopped responding to standard hormone therapy. These trials have shown that using it at an earlier stage, from diagnosis, could be beneficial for patients.

Professor Nick James, Professor of Prostate and Bladder Cancer Research at the ICR and Consultant Clinical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, is Chief Investigator of STAMPEDE. He says:

“STAMPEDE has delivered practice-changing results. Its depth and breadth have allowed us to examine aspects of care not studied in other trials. Through STAMPEDE, we’ve been the first to show that abiraterone can benefit men whose prostate cancer is at an earlier stage – improving survival and reducing the chance of progression. These, and other, findings have changed the standard of care worldwide.

“The linked biological studies on donated pathology samples and trial imaging have provided key insights into the biology of advanced prostate cancer."

In our Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery, we are working to create more and better drugs for people with cancer. But the life-saving research that is taking place within it relies on your support. Please donate today to help more people survive cancer.

Extending the lives of men worldwide

The discovery and development of abiraterone has helped to extend the lives of thousands of men with prostate cancer around the world. Rob Lester, Alfred Samuels and Tony Collier are three patients whose lives have been hugely impacted by abiraterone.

Alfred Samuels – patient advocate, author and film maker

Alfred Samuels was diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer in January 2012. His PSA levels, an indicator of signs of prostate cancer, suggested severe disease and he was told by the doctors to “think short-term”. With his lengthy career in the entertainment security industry ending abruptly, and his health deteriorating quickly, Alfred had started to lose hope.

Image: Alfred Samuels. Credit: Alfred Samuels

His wife found out about the STAMPEDE trial, and in March 2012 (on the week of his 54th birthday) Alfred started treatment with abiraterone and Prostap, a form of hormone therapy.

The treatment was very effective at reducing his testosterone and PSA levels quickly. He said: “When I started on the STAMPEDE trial my initial PSA reading was 509 ng/ml, when a normal reading for a man my age should have been between two and four. Over the next seven months, I was amazed to see my PSA levels had reduced to less than 0.1 ng/ml.

“Abiraterone saved my life. It has given many men like me, and their families, extended time together and improved their quality of life.

“Thanks to the treatment, I have been able to live to meet six grandchildren and play a part in their lives. This importance cannot be overstated. Abiraterone has allowed me to find a new life and reinvent myself as time has progressed. Today I am a published author, a TV documentary scriptwriter, a patient advocate, a cancer charity ambassador and much, much more.”

Rob Lester – retired GP

Rob Lester is 66 and lives in Dunfermline, Scotland. He was 55 when he was diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer which had spread to his bones. As a GP himself, he felt frustrated by not being able to catch the cancer sooner.

He remembers his shock at the diagnosis, especially as he had never seen anybody as young as him with prostate cancer before, nor was there any history of the disease in his family.

The aggressive nature of Rob’s cancer meant that his prognosis was not good. Fortunately, he was given the option to go on the STAMPEDE trial, where he was put on the ICR-discovered drug abiraterone.

Image: Rob Lester. Credit: Rob Lester

He said: “I started treatment with abiraterone in May 2012, following my diagnosis in February 2012. For the first six months, I had feelings of tiredness which were easy to cope with, as I simply got into the habit of going to bed every afternoon for a two-hour nap. There were other minor problems such as a short spell of raised blood pressure and a transient rise in one of the liver function tests. All these issues were resolved within six months.

“After taking Abiraterone for three months, there was a significant reduction in my PSA from a peak of 47 ng/ml at diagnosis to less than 0.1 ng/ml. I continue to get abiraterone through the hospital that organised the STAMPEDE trial and have now been on the therapy for 11 years. My PSA remains at less than 0.1 and I feel marvellous!

“When I was diagnosed in 2012, I didn’t think that I would still be alive after 11 years. Thanks to abiraterone I have been well enough to travel abroad as much as I want to, see my grandchildren grow and go to my daughter’s wedding in Germany. Not a bad life for someone with advanced prostate cancer!”

Tony Collier – patient advocate and Prostate Cancer UK ambassador

Tony Collier was diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer in May 2017, aged 60, and was given a worst-case prognosis of two years. He was originally scheduled to start immediate hormone therapy followed by chemotherapy, but when he heard about the results from the first abiraterone trial that was presented at the 2017 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting in Chicago, it changed the course of his treatment journey.

Image: Tony Collier. Credit: Tony Collier

When Tony learned about the drug, he asked his oncologist whether he could be put on it through his private medical insurance. He started on abiraterone in June 2017 and has been on it for more than five years now. Abiraterone has kept Tony’s cancer under control so far, enabling him to live every day to the fullest and enjoy his time with his grandchildren.

He said: “My grandchildren are massively important to me. I had one grandchild when I was diagnosed, and he was three years old. I didn't expect to get to see him become a teenager. He's now coming up to 10 and since then, I've had three more grandchildren. They are my life and absolutely fill me with joy! I'm desperately keen to be around to see them grow up.”

Tony, who is an avid runner, a patient expert on the value of exercise for people living with cancer and a passionate advocate for healthcare equality, acknowledges how fortunate he has been to have initially accessed abiraterone via private medical insurance. Unfortunately, he can no longer afford the premium on his medical insurance to get abiraterone privately, but luckily his oncologist has managed to find a way for him to receive it on the NHS for the last two years.

He expressed his disappointment at the fact that abiraterone is not available as a first-line treatment on the NHS in the UK, apart from in Scotland, despite being used to treat more than 500,000 men with advanced prostate cancer worldwide. He said: “For some men, abiraterone as a first-line treatment is a complete godsend. People should be able to access the best treatment that's most appropriate for them and their circumstances.”

Help us find tomorrow’s cancer treatments

The ICR’s research has given many men like Alfred, Rob and Tony a new lease of life. Over the coming years, more men will be able to benefit from abiraterone and be given the opportunity to live longer and better-quality lives.

The ICR is committed to defeating cancer and continues to lead cutting-edge research in prostate cancer that will help to detect and diagnose cancers early, bring new drugs to treat the cancer more precisely, and tackle cancer drug resistance.

Our pioneering drug discovery research is transforming the lives of cancer patients across the world, helping them live longer and better. Please donate today to help us find tomorrow’s cancer treatments and help more people survive cancer.