The following piece deals with post mortems in children with cancer. We know it's a sensitive topic, but we felt it was one that was important to be discussed.

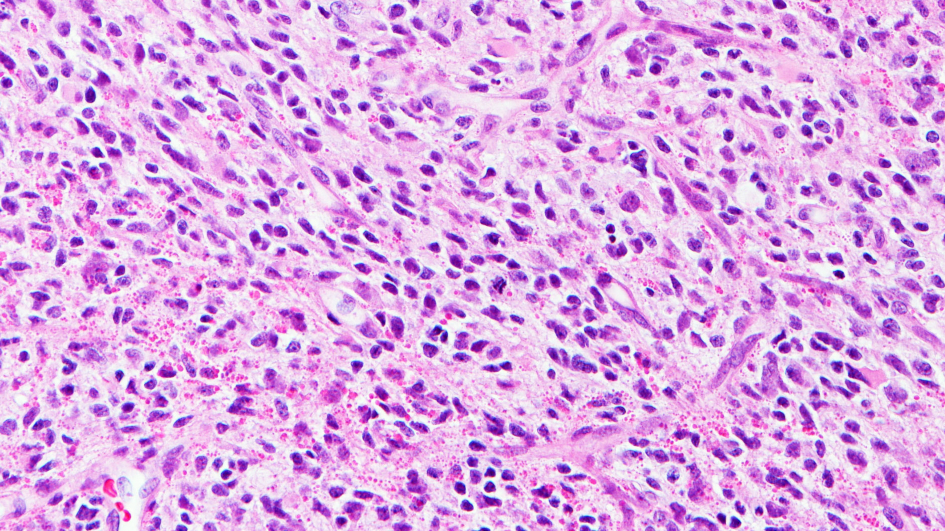

Image: Infant high-grade glioma. Credit: David Ellison, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

"You just perform post-mortems, don't you?" This is the response I frequently get from members of the public when I say I am a pathologist. We can’t really blame them for this; when they see pathologists on television, they feature in programmes such as ‘Silent Witness’ where the forensic part of the specialty (and therefore post-mortems, where a pathologist examines the organs of person when they have died to work out the cause of death) is showcased.

However, this is such a small part of the specialty and is dwarfed by the volume of work performed by pathologists and scientists working across a total of 17 different subspecialties. 95% of the work performed by a cellular pathologist is undertaken on behalf of living patients and 95% of clinical pathways rely on patients having access to pathology services. Pathologists and scientists are often unseen by patients, but they are very much present, working behind the scenes to support ongoing health and treatment.

I work as a registrar in diagnostic neuropathology, and my day-to-day work is focussed on diagnosing diseases of the nervous system and muscle. I also work in research focussed on paediatric brain tumours, specifically high-grade gliomas (HGG). It is a devastating disease for patients, their families and clinicians. However, there is a hugely important role for research; in recent years, by performing a variety of different complex tests (molecular profiling) on tumour samples, important vulnerabilities have been identified which have been exploited to improve outcomes for some patients.

My work on infant gliomas (which was the focus of my PhD in the Jones Lab at the ICR) identified a group of tumours characterised by the presence of a fusion which is treatable. As a result of this work, a new tumour is now recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) classification, and clinical trials have been developed for these patients, who are now surviving. Importantly, it has provided these and other families with hope and shown how important continued research is.

However, there is still much more work to do. Which brings me back to the quote which starts this article. Death and dying are not topics people enjoy talking about. As clinicians, we also do not like talking about it. However, it is a fact of life, and for cancer patients, it is an all too familiar reality. As researchers, we strive to give patients as much time as possible, and hopefully survive their disease. But we also avoid talking about post-mortems; by letting the emotions of an awful situation take primacy, are we missing a vital insight into the cancer ecosystem – the end point?

Most children diagnosed with HGGs undergo chemotherapy and radiotherapy to treat the tumour, and serial radiological monitoring to check treatment responses. Studies are ongoing to explore reliable methods of monitoring tumour response (including liquid biopsies), but we are lacking the finer details of tumour evolution provided by a tissue sample. Secondary biopsies/resections are performed in certain situations, providing a snapshot of the tumour’s molecular characteristics at that time point. However, I think there is still more to gain.

Post-mortems provide a vital opportunity to sample the whole tumour at the time of death. We get a broader understanding of the variability of the different tumour regions and can compare molecular features at different time points, including the start and at the end. We can assess how it has changed microscopically and molecularly in response to treatments, or as a result of its inherent evolution; understanding the role of these changes and the advantage they give to cancer cells can provide a window of opportunity to break this.

It is very rare for post-mortems to be undertaken in children who have died of brain tumours. Understandably, it is a hugely emotional time for families who are grieving the loss of a loved one. There is also a reluctance of neuro-oncology teams to have conversations about this; for a specialty that features some of the best communicators in all medicine, I think we can appreciate how challenging this is. However, it is time to swallow this uncomfortableness and start these conversations more openly.

Interestingly, patient groups are engaging with these discussions. And in cases where a post-mortem is performed, it is often the patient/family who have initiated the conversation first; it provides some comfort that good can come from something so awful, providing researchers with a new angle to explore tumours.

But I think we can go further still. Rapid autopsies (those that are performed very shortly after death) can provide a more detailed view of the tumour at death. Not only can it provide better quality data, there is the potential for cell cultures to be developed and from multiple tumour sites.

Growing live cancer cells opens up opportunities to engage with pre-clinical studies, to properly characterise the molecular features of different tumour cells, test and validate different treatment strategies that can ultimately make a significant difference for future patients. As a profession, we need to develop this into a proper ‘on call’ service; engagement with the pathology workforce is vital.

As clinicians and researchers, we need to address the underlying uncomfortableness in having difficult conversations about post-mortems. And I think we need to expand the service we could offer to patients by thinking about the provision of rapid autopsies. Until we do, cancer will always be one step ahead of the game.

This option will not be suitable for all patient families, and this should be entirely respected. However, the willingness of some families to engage shows us that they want to help in any way they can, and we need to be communicating with them what we want and need to advance research. Looking at tumours from every angle, leaving no stone unturned, and at all time points will give us a detailed map of how they develop, evolve, and the opportunity to halt the cycle.

This piece won the 2022 Mel Greaves Science Writing Prize.

Read more entries from the finalists

______________________________________________________________________

Dr Matt Clarke is a trainee neuropathologist and currently holds an NIHR Clinical Lecturer post in Diagnostic Neuropathology.

He first joined the ICR in 2016 as part of the BRC Molecular Pathology Starter Programme, and became a member of the Glioma Team headed by Professor Chris Jones. He completed a PhD on the molecular pathology of infant gliomas in 2021.

His current position allows him to continue his clinical neuropathology training at the National Hospital of Neurology and Neurosurgery (UCLH) whilst also pursuing his research interests at the ICR. Matt's current project is focused on exploring high-grade gliomas in teenagers and young adults.