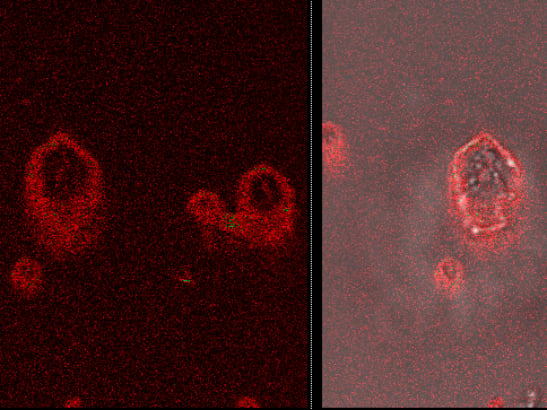

Image: Apoptotic (dying) cells captured using a multiphoton microscope. Credit: Anant Shah, ICR

All living organisms, from bacteria to humans, are made up of cells, and each one comes from a pre-existing mother cell. However, it is not the destiny of every cell to become two. Many are born to meet a very literal dead end. This cell death or cellular suicide has intrigued scientists for centuries. It is now giving us the clues to defeat cancer by breaking a major barrier: opening a direct line of communication with the body’s defence mechanism – the immune system – to destroy cancer cells.

Nearly 2,000 years ago, the Roman emperor Hadrian commissioned the restoration of the Pantheon, including its majestic concrete dome. Today, it still stands untouched by time. Only imagination can take us back to what the building site must have been like: scaffolds, workshops, dust and frenetic human activity. It is all long gone now, leaving one of the most mysterious architectural feats in the world.

In our embryonic days, our body was no different to the Pantheon’s building site – with equal architectural feats. Cell death is the clearance. It disassembles the scaffolds, puts on the finishing touch, and throws away the unwanted and unfit. The grim reaper makes space, hollows our digestive tubes, separates our tied fingers, quality checks our young immune system. Death sculpts the living and leaves no traces of its labour.

Destined to die

In 1842, German scientist Carl Vogt published his breakthrough work on tadpole development. He stated that it is the destiny of certain cells to intentionally die. The concept of programmed cell death was born. To understand how controversial this was at the time, we need to imagine the shock of discovering that death participates in the very beginning of multicellular life, from worms to men. This is the inconceivable statement that death takes part in the making of who we are. It took until the 1970s for scientists to finally give a name to this taboo phenomenon: apoptosis. In the words of the authors, it “is used in Greek to describe the ‘dropping off’ or ‘falling off’ of petals from flowers, or leaves from trees”. A very poetic image for a very grim event, a cellular suicide.

If clearance and pruning during development were the only roles of cell death, it would have indeed been very poetic. However, with the new millennium came major advances in our understanding of cellular suicide, and with it, a dark truth: cell death is not a benevolent architect, it is a weapon of war.

Stealthy predators roam our world and once they get inside us, it is often too late. Viruses are the ultimate enemy of our immune system. For billions of years, in the greatest arms race of all time, living beings have constantly evolved to defeat these tenacious foes. But viruses evolve too. Last resort tactics have to be taken: sacrifice the few to save the many. Bacteria too suffer from viruses, and if the virus is inside them, the battle is already lost. Last year, groundbreaking work showed that bacteria’s antiviral defence systems trigger bacteria to die. In doing so, the bacterium explodes to save the colony and, with its last breath, transmits alarm signals for all neighbours to hear: Be aware! Be prepared! Prevention is key in the fight against viruses.

The same principle holds true in our body. These death events are not like apoptosis, well organised and well behaved. They are dirty, messy and noisy. They have warrior names: necroptosis [necro: death], pyroptosis [pyro: fire]. Cells that can commit to these types of cell death are sentinels, waiting to spot the enemy to ring the alarm. Our immune system reacts ferociously to the alert. Immune cells hit the location with full force, unforgiving, scouting cell by cell to reveal infected culprits. Without pity, the immune system will destroy every single one of them.

Harnessing the immune system

At The Institute of Cancer Research, London, our mission is to make the discoveries that defeat cancer. Our research has taught us that the ultimate weapon against cancer is our immune system. Without its help, the titanic enterprise of clearing cancer out of the patient’s body is quickly outrun by the tumour’s uncontrolled growth and the refusal of cancer cells to commit to cell death. However, a major barrier stands in our way. How do we communicate with the immune system? How do we speak its own language? How do we convince it to keep fighting and not to retreat? There is a war the immune system will never back down from: the war against viruses.

Oncolytic Viruses [onco: cancer; lysis: breakdown] are used in cancer treatment to destroy cancer cells and alert the immune system. However, one round of treatment is not always enough to eradicate the tumour and the body becomes quickly immune to the viruses we use. The clinical arsenal of oncolytic viruses at our disposition is growing, but it is still limited. So, very recently, scientists working on cell death have taken a leap of faith. What if we did not use viruses, but made the immune system believe we did? This could be used over and over again as the body cannot build an immunity to a lure! They caused artificial Necroptosis and Pyroptosis to happen near to or within the tumour in mice – it was a breakthrough.

Upon inspection, the immune system, which came looking for viruses, detects the cancer and attacks, achieving both the destruction of the tumour and a long-lasting immunity against it. We are now working to adapt this strategy to treat people with cancer. Notably, this includes finding drugs to cause Necroptosis and Pyroptosis in patients, compatible with current treatments, and with minimal side effects. The road is still long ahead of us, but major progress is within reach. If successful, we will have once again proved that cell death guards the integrity of our body. That death preserves life.

Read the other submissions for the Science Writing Prize 2020