Human colon cancer cells in culture. Image credit: Wellcome Collection. License: CC BY 4.0.

It was a morning like any other when my dad woke up in the early hours to go to the bathroom. He was almost 60 after all – nothing unusual about going to the toilet in the middle of the night.

What was strange though was the damp feeling he had as he stood up. Maybe it’s the piles again, he thought, as he turned on the light. To his horror, blood was everywhere. Sensing something was amiss, my mum woke up and called out to him, but by then he was unresponsive from severe blood loss. She called for an ambulance immediately.

Once at the hospital, a colonoscopy revealed the cause – an angry lump the size of a golf ball protruding out the side of his rectal lining. Colorectal cancer. The tumour had invaded through the tissue, presumably leading to the dramatic bleeding.

After his first surgery to remove the tumour, a follow-up CT scan revealed that a dark spot in his liver appeared to be responding to chemotherapy, indicating the cancer had spread. A second surgery was scheduled to remove the secondary tumour. My dad is now undergoing his last round of chemotherapy, while we cross our fingers and hope that his cancer does not return.

Spotting a zebra amongst the horses

Since his diagnosis, friends and family have expressed shock and even anger that doctors had not picked it up earlier – after all, he had blood in his stool. But he also had haemorrhoids, which cause the same symptoms. And his colonoscopy three years’ ago showed nothing suspicious. Neither he nor his doctor had felt there was anything sinisterly wrong with him.

And there lies the danger of colorectal cancer. It is often passed over for more common gastrointestinal ailments, as the symptoms are similar – frequent constipation or diarrhoea, abdominal pain, unexplained weight loss. It is often quoted in medicine, ‘when you hear hooves, think of horses not zebras’. This adage works well for most cases, but when the metaphorical zebra is cancer, the risk of calling it a horse is simply much too high.

Patients with persistent symptoms may go for multiple consultations before cancer is even mentioned, or as in my dad’s case, assume their symptoms are unrelated to cancer and put up with it until that fateful rush to the emergency room.

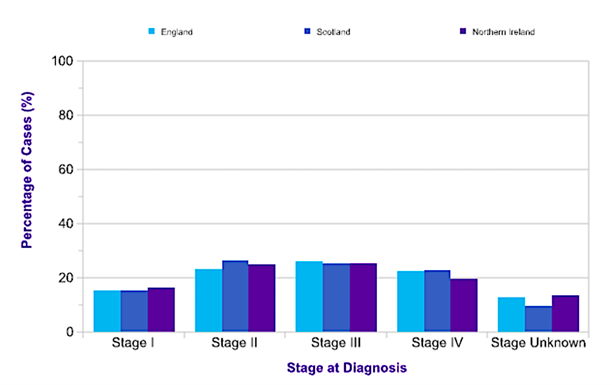

Because of this, colorectal cancer is often discovered at a later stage, when the tumour has already locally invaded (stage III) or invaded to other sites (stage IV), as the graph below shows. Late-stage cancer can be more difficult to treat, and is associated with a lower survival rate.

Figure 1: Colorectal cancer cases separated by stage at diagnosis. Source: www.cancerresearchuk.org

Screening for better outcomes

Because of the dangers of a late diagnosis, public awareness of possible symptoms and screening for early detection are important strategies in the fight against cancer. In recognition of this, national screening programmes for colorectal cancer were introduced in the UK in 2006.

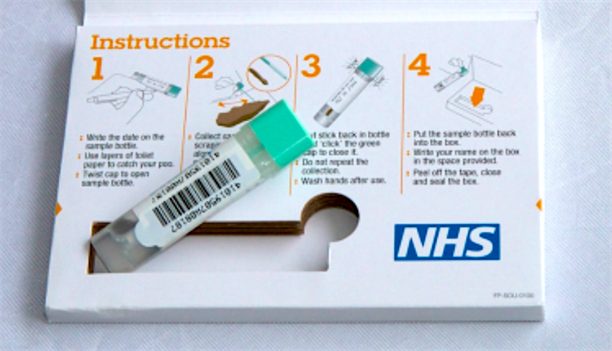

The likelihood of getting colorectal cancer increases with age, and rises steeply around 50. And so, after turning 50* a ‘birthday present’ arrives in the mail from the doctors in the form of the FIT (Faecal Immunochemical Test)#. The FIT is an at-home kit that requires small samples of your Number 2 that get mailed away (in a sealed and hygienic way), and tested for blood. Blood in the stool without any history of haemorrhoids is a red flag for something nasty brewing in the colon.

The Faecal Immunochemical Test supplied by the NHS tests for blood in faeces, a possible sign of colorectal cancer. Source: www.bowelcanceruk.org.uk

After a positive FIT result, doctors use a small camera at the end of a flexible tube, or endoscope, to check the bowel for any visible signs of abnormality. Additionally, anyone over 55 in England is eligible for a one-off bowel scope that – with follow-up treatment – is able to reduce the risk of mortality by 30-40%.

Typically, after the all-clear at this stage, another colonoscopy will not be needed for another 10 years. But even with a negative result, it is important to remain vigilant and monitor the body for any changes. Some doctors have even recommended repeat colonoscopies if regular FIT testing shows positive results, as some cancers can develop within the 10-year period, as happened with my dad.

Despite the national screening programme, in 2016, only a minority of colorectal cancer cases were discovered through screening (10%). The vast majority were referred by their GPs (55%) or through emergency admissions (20%).

Clearly, it is not enough to just have a screening programme; people also need to be encouraged to take part in it. The current response rate to colorectal cancer tests is only just above half, at around 55%. Compare this to breast and cervical cancer screens, where the uptake rate is just over 70%.

Breast cancer is a good example of the power of public awareness and screening. Although it is the most common cancer in the UK, which might make it more dangerous, it actually has more survivors than colorectal cancer.

People’s reasons for not getting screened are numerous and varied – discomfort about discussions and examinations involving their bowels, finding it a hassle to mail the kit back or show up for appointments, belief that because they have no symptoms they do not need to be tested, or conversely, anxiety about a positive result if they do have symptoms.

Regardless of the reason, it is important to remember that the likelihood of finding something life-threatening is minor. Less than 15% of FITs show a positive result, and of these only a minority end up being cancer. Additionally, the FIT can pick up signs of other illnesses, providing additional protection from disease. And if further tests find anything wrong with the bowel, it is far better to have found it earlier rather than later.

Worryingly, as lifestyle changes occur and gastrointestinal diseases increase, more and more younger people are being diagnosed with late-stage colorectal cancer. But because colorectal cancer is often associated with ageing, younger people are even more at risk of being overlooked until their cancer has advanced.

Colorectal cancer is not a disease that is about to go away anytime soon. All the more important that we figure out now how to promote recognition of symptoms and early screening, because early detection saves lives.

Dr Maxine Lam is Postdoctoral Training Fellow in the Division of Cancer Biology.

* – England, Wales and Northern Ireland currently start screening at 60, but are set to transition to starting at 50 in 2019.

# – Currently the faecal occult blood test (gFOBT) is being used in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, but will switch to the FIT. The gFOBT requires multiple stool samples that may discourage people from participating in screening.