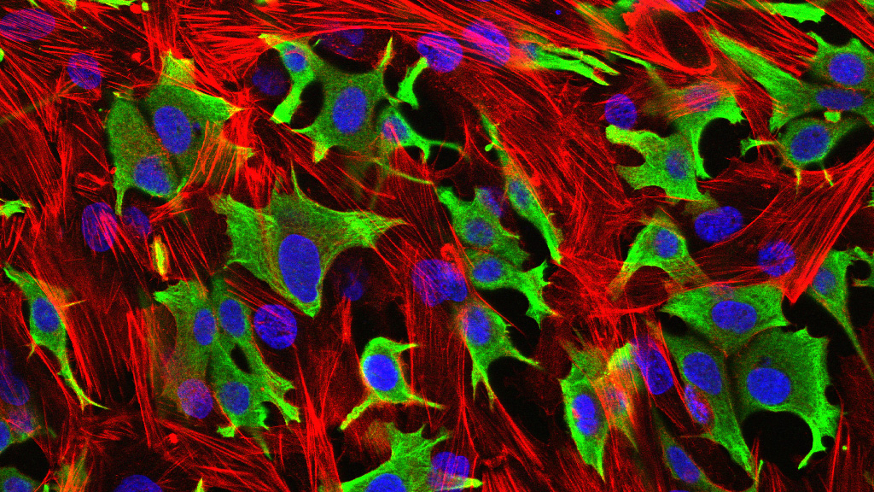

Breast cancer cells (green) invading through a layer of fibroblasts (red). (Luke Henry / the ICR, 2009)

There has been a major treatment breakthrough in the past few years for cancer patients with mutations in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 – better known in the media as the ‘Angelina Jolie genes’.

Mistakes in the DNA sequence of these genes can significantly increase a person’s risk of several cancers, most notably breast and ovarian cancer.

But a new family of drugs called PARP inhibitors can specifically kill cancer cells with faulty BRCA genes, while leaving healthy cells alone.

One such drug, olaparib, was approved on the NHS for patients with advanced ovarian cancer who carry BRCA mutations, after a phase II clinical trial showed the drug considerably delayed progression.

Slows breast cancer

Now, a major international phase III clinical trial of 302 patients has shown that olaparib delayed the progression of advanced breast cancer in women with inherited BRCA mutations for 42 per cent longer than standard chemotherapies.

The data was presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting 2017 in Chicago this weekend, and simultaneously published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine.

Olaparib was found to halt the disease for 7 months, compared with 4.2 months in women who received standard chemotherapies.

Importantly, patients taking olaparib also experienced fewer side-effects than standard chemotherapies.

Find out how ICR researchers identified the BRCA2 gene.

Good news

This is good news for patients, and also for us here at The Institute of Cancer Research in London. It was 20 years of research carried out here that underpinned the development of olaparib as the world’s first licensed treatment targeted against an inherited genetic fault.

Reacting to these results, Professor Andrew Tutt, who is Director of the Breast Cancer Now Research Centre at the ICR, and who was himself part of the early laboratory research on PARP inhibitors, said:

“It is fantastic news that olaparib delays the progression of advanced breast cancer in women who have inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations – the most common type of inherited breast cancer.

“Olaparib is already available for women with BRCA-mutant advanced ovarian cancer, and is the first drug to be approved that is directed against an inherited genetic mutation. It is a perfect example of how understanding a patient’s genetics and the biology of their tumour can be used to target its weaknesses and personalise treatment.”

How it works

Professor Alan Ashworth, a former Chief Executive of the ICR, Professor Tutt and colleagues discovered that the protein produced by the BRCA2 gene plays a key role in repairing DNA. This means cancers with BRCA mutations are particularly vulnerable to DNA damage.

Some years later, Professor Ashworth, Professor Tutt and ICR Team Leader Dr Chris Lord were able to show in the laboratory that you could target this weakness, using drugs called PARP inhibitors to cause breaks in DNA that BRCA-defective tumours struggle to repair. Using PARP inhibitors, such as olaparib, caused BRCA-defective tumour cells, but not normal cells, to die.

And these results translated into the clinic, where phase I trials of the PARP inhibitor olaparib – designed and led by ICR Professors Johann de Bono, Tutt and Stan Kaye at the ICR and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust – found that olaparib was effective against tumours with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, and had fewer side-effects than many traditional chemotherapies.

More to do

Although the results are encouraging, there is still much more to do to extend and improve the lives for patients with advanced breast cancer.

Two thirds of the 55,000 breast cancer patients diagnosed in the UK each year can expect to live for at least 20 years – but for many of these long-term survivors, their disease will have been caught early.

Professor Tutt explained: “We are getting much better at curing patients with breast cancer that is diagnosed early – but once the disease has spread around the body, it is much more difficult to treat. We need to see more innovative new cancer drugs like olaparib being developed, to give these women a better quality of life for longer.”