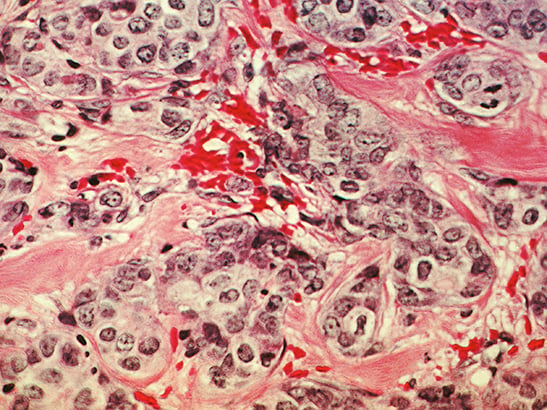

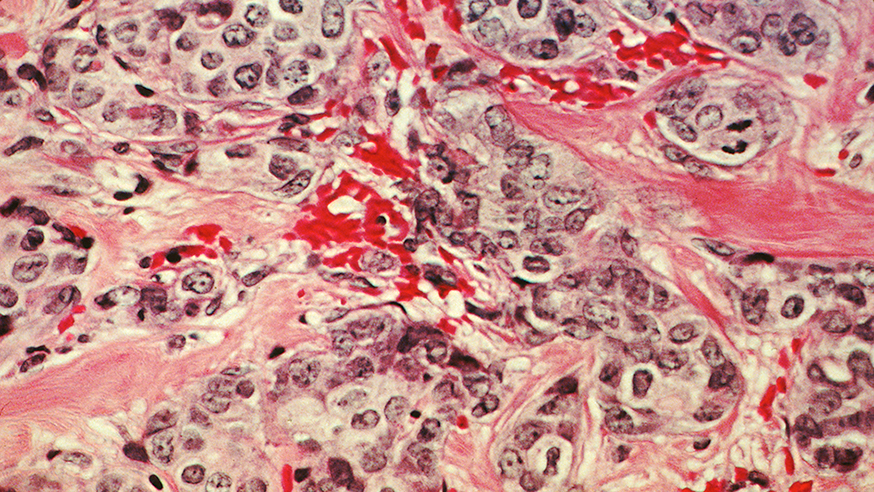

A histological slide of cancerous breast tissue. (photo: Dr Cecil Fox/National Cancer Institute

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are perhaps two of the most famous cancer genes known to science.

Their discovery, more than 20 years ago, explained why some breast and ovarian cancers run in families. They hit the headlines once more when Angelina Jolie announced her decision to have preventative surgery after finding that she carries a faulty copy of the BRCA1 gene, which puts her at increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

Shortly after, the genes were back in the spotlight when the US Supreme Court ruled out that the genes could not be patented, preventing a monopoly on testing patients for these mutations.

But amidst the BRCA maelstrom, I have been hearing the term ‘BRCAness’. Wanting to find out how this differs from BRCA, I spoke with Dr Chris Lord – leader of the Gene Function Team here at The Institute of Cancer Research, London – who has recently written an opinion piece on the subject in the journal Nature Reviews Cancer with former ICR CEO Professor Alan Ashworth.

BRCA versus BRCAness – what’s the difference?

After twenty years of work on BRCA1 and BRCA2, we now have a good understanding of how these genes work. Faults in either BRCA genes cause tumour cells to lose a specific DNA repair mechanism called homologous recombination.

Around a decade after the discovery of the BRCA genes, Professor Ashworth, Professor Andrew Tutt, Dr Nicholas Turner and others proposed that defects in the homologous recombination repair mechanism might also be apparent in a tumour that doesn’t hold a hereditary BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation – a concept termed ‘BRCAness’.

Further research revealed that BRCAness can stem from defects in other similar genes. Dr Lord told me that this calls into question if therapies used for patients with for BRCA mutations, such as PARP inhibitors, could be used in tumours that display BRCAness.

Can we treat BRCAness?

One of the major treatment breakthroughs for patients who hold a BRCA mutation has been PARP inhibitors, which selectively kill cells where homologous recombination DNA repair is absent. Olaparib – whose development was underpinned by Professor Ashworth’s and Dr Lord’s research at the ICR – has been a huge success, and is now approved for women with BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer.

But Dr Lord tells me there are several unanswered questions on how to treat BRCAness. Perhaps the most important question is how we predict which patients will have a favourable response to drugs that target homologous recombination repair, such as PARP inhibitors.

Developing and refining molecular biomarkers that detect BRCAness and defects in homologous recombination repair will help to overcome this hurdle. Research at the ICR is already making headway, with Dr Turner identifying one of these molecular biomarkers, and Professor Tutt has also led much of the work in this area.

Another major barrier is drug resistance. There is already an initial understanding of what might drive clinical resistance to PARP inhibitors in BRCA1- or BRCA2-mutant tumours.

In 2008, Professor Ashworth and Dr Lord identified additional mutations in BRCA2 that, perhaps surprisingly, cause drug resistance rather than drug sensitivity in BRCA2 mutant patients. Despite these advances, there is little understanding of routes of resistance when, for example, the initial PARP inhibitor response is driven by a mutation in another gene, other than BRCA1 or BRCA2 that leads to BRCAness.

What’s next for BRCAness?

When first identified, it was thought that BRCAness might exist in a small fraction of ovarian and breast cancers, Dr Lord tells me. But recently, it has become clear that significant proportions of prostate and pancreatic tumours, among others, might also exhibit BRCAness, and this is something we need to explore further.

Robust methods are yet to be developed and established for the assignment of BRCAness to tumours. Once these are in place, we can start thinking about introducing these to the clinic and matching the appropriate treatment to the patient.

Finally, it is not clear for the majority of tumours what, at the molecular level, drives BRCAness in the absence of a mutation in a gene contributing to homologous recombination repair.

Regardless of the continuing conundrum of how to treat and define BRCAness, this type of extensive understanding of a biological variant is quite rare in cancer research. BRCA and BRCAness have become models for studying and understanding core processes in cancer cells, and how we treat cancer in a targeted way.

Research at the ICR has already led the way in understanding these processes – in time we hope to use this information to refine the way people with BRCAness cancers are treated.