Despite the fantastic leaps and bounds being made in our understanding of cancer, some types of the disease remain frustratingly difficult to beat.

Lung cancer accounts for 6% of all recorded deaths in the UK each year – nearly as many people die annually from the disease as bowel, breast and prostate cancer combined, and only 10% of patients survive five years after diagnosis. But modern drugs are gradually beginning to improve the landscape for patients with lung cancer.

In a review published in the journal Pharmacogenomics and Personalised Medicine, Dr Timothy Yap from The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, and Dr Sanjay Popat from The Royal Marsden, looked at how three generations of lung cancer drugs are demonstrating the power of precision personalised medicine.

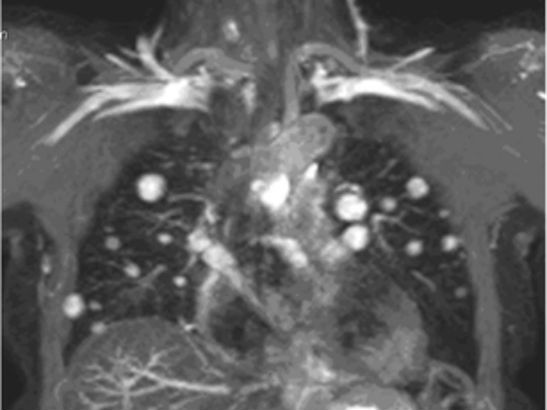

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) makes up almost 90% of lung cancer cases, and compounds called tyrosine kinase inhibitors can target a gene called EGFR, which is mutated in approximately 10% of cases of the disease in the UK.

Lung cancer cells with faulty EGFR genes become addicted to EGFR for their growth and survival, so blocking the gene’s activity is an effective way to kill them.

Erlotinib and gefitinib were part of the first generation of targeted lung cancer drugs and they offered significant improvements for some patients over standard chemotherapy.

Clinical trials of the drugs have shown they can prevent a patient’s lung cancer from getting worse for an average of 10 months, proving that targeting EGFR addiction is an effective treatment for lung cancer.

But despite improvements for some, between 10% and 30% of patients tested saw no benefit because their cells didn’t respond to treatment, while all patients eventually developed resistance over time.

Smarter targeting was needed, and over half of patients who became resistant to these first generation treatments had a specific mutation to EGFR called T790M, so the second generation of targeted drugs were designed to inhibit these cells as well.

The most successful second generation drug is afatinib, which inhibits both EGFR and a gene mutated in cancers like breast cancer, called HER2. A clinical trial carried out at the ICR’s and The Royal Marsden’s Drug Development Unit was one of the first to show that afatinib was effective in patients with EGFR mutations, including T790M.

And a study pooling data from two phase III trials found that afatinib can gave patients with common EGFR mutations an extra three months on average to live, when compared with standard chemotherapy, showing for the first time that the drug can improve survival for lung cancer.

Now, the third generation of targeted lung cancer treatments are promising to hit lung cancer cells even more precisely. These drugs can specifically target cells with EGFR T790M mutations, leaving cells without these mutations alone, and are some of the most specific drugs available today.

A promising third generation drug is called AZD9291, and the Drug Development Unit is just about to begin a phase I trial looking at specific clinical pharmacological effects of the drug in patients. Future trials are likely to involve looking at how best to combine these drugs to improve response rates and prevent resistance developing for patients with NSCLC.

The ICR is looking for more druggable targets for other types of cancer, and these three generations of targeted lung cancer treatments exemplify how precision medicine could one day transform treatment for many more patients with cancer.