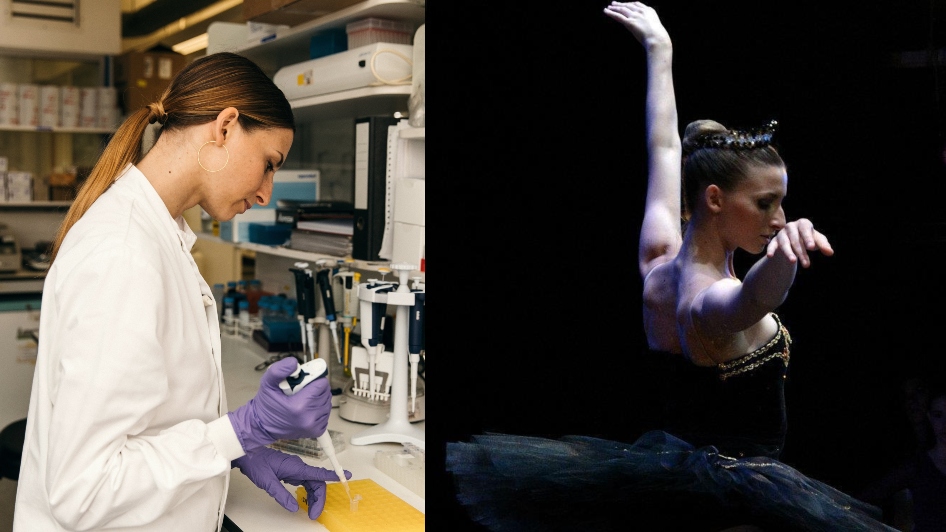

Image: Dr Camilla Rega (left), Dr Vivian Dimou (middle top), Dani Chattenton (middle bottom) and Dr Ana Padilha (right) pursuing their passions outside the lab. Credits: Tom Joy for the Accessorize 'Everything You Are' campaign, Vivian Dimou, Unknown, Ana Padilha

One of the damaging stereotypes in science is that you can’t have a life outside the lab. But, that’s not true. Having hobbies and interests besides work is important – it’s part of what makes our scientists who they are, and it also makes science better as a whole.

This year, the theme for International Women’s Day is #BreakTheBias, and we wanted to challenge this idea by celebrating life outside the lab. We want to showcase the full lives and passions of our researchers and the importance of creating environments that support this balance rather than stifling it.

We spoke to four of our researchers about their lives outside the lab. In many cases, they described people being shocked they were scientists – as well as dancers, musicians, runners and bakers. Here, they share how these interests have helped their wellbeing and also helped them with their research.

Vivian Dimou - immunologist and pianist

Dr Vivian Dimou is a Postdoctoral Training Fellow in the Thoracic Oncology Immunotherapy Group, led by Dr Astero Klampatsa. Vivian’s research aims to explore the ‘immune universe’ of patients with mesothelioma (a type of cancer that mainly affects the lining of the lungs), and how it might differ from that of healthy people.

She explained: “I use samples from patients with mesothelioma and try to work out how their cancer’s immune microenvironment might be accounting for exacerbation of their disease – in other words, how the immune cells surrounding their tumour may be helping to make their cancer progress.

“My research is helping to discover which immunotherapies would work best for different patients, helping to predict how patients will respond to new immunotherapies, and finding a more personalised way to treat people with cancer.”

Vivian did her undergraduate degree in her home country of Greece before moving to the UK on an Erasmus programme.

“When I was doing my undergrad, everyone assumed I was studying to be a kindergarten teacher,” she remembered. “I love kids, but that wasn’t why they assumed that! It was just because of the way I look. Even now, when I explain I am a scientist, most people are shocked and impressed.”

“Being a woman who doesn’t look like what most people would imagine a scientist to typically look like has definitely presented some challenges for me,” she said. “There is still a long way to go before equality in science is achieved.”

Alongside her science, Vivian has a great love of music. At the age of four, inspired by her kindergarten music teacher, she started learning to play the piano, and developed her talent over the years that followed. When she left home at 18, Vivian’s parents bought her an electronic piano to take to university, but she found it hard to keep up with playing – until the pandemic when she found time to play again.

She said, “The pandemic was so distressing, but it had an amazing aspect for me, as I was able to reconnect with my piano abilities. I started posting some videos online of me playing, and I truly enjoyed it. It had been ages since I had felt such joy in my heart. The sense of wellbeing that piano gives me is enormous.”

Reflecting on the ways science and music complement each other, Vivian said: “My science has been much better since I started playing the piano again. It’s a great way to vent, and get rid of any frustration I experience at work.”

“Looking at the musical notes and trying to decipher a piece is almost the same as planning an experiment. You’re brainstorming, trying to optimise. Piano helps to enhance my creativity, it gives me different ways of thinking.”

“When I meet new people, I always find it quite fun to combine two surprises in one sentence: I am a scientist, and I also love playing the piano.”

Camilla Rega - molecular biologist and ballet dancer

Credit: Tom Joy for the Accessorize 'Everything You Are' campaign

Dr Camilla Rega is a Postdoctoral Training Fellow in the Short Linear Motif Team, led by Dr Norman Davey. Her research looks at protein interactions involved in cancer.

She said: “Defects in protein interaction can result in catastrophic events in our health and ultimately lead to diseases. Uncovering protein interactions, and understanding their perturbation in cancer, will help us to design more effective drugs. My research is mainly focused on the development of cutting-edge technologies for protein interaction discovery.”

Camilla joined the ICR in September 2019, after completing a PhD in biomolecular science in her home country of Italy.

“I never thought I wanted to be a scientist,” explained Camilla, “but when I actually got into the lab and started doing experiments, I really enjoyed it. My previous work was mainly focused on studying protein interactions in vitro, and I came to London to join the ICR, because I wanted to move into the cancer field.

“When I tell people I’m a scientist, they’re often quite impressed. Scientists are seen as doing high impact jobs and probably a lot of that image comes from not knowing what happens in a lab – many people don’t know what scientists do on a day to day basis, so they don’t really know what to expect.”

“I think the other issue is that often people don’t expect a scientist to be a woman. I’d encourage everyone to watch the documentary ‘Picture a Scientist’ (which is now available on Netflix) that essentially asks the question: ‘when you think about a scientist, what do you picture in your mind?’ Unfortunately, for a long time, the answer to that question has been men.”

“But I consider myself incredibly fortunate to have had the privilege of being mentored by so many bold women. I think the gender imbalance is less obvious in the early stages of a scientific career, where I am now, but as you move up the academic ladder it becomes more prevalent. I think we need to have more of the inspiring examples of women in leadership positions that I had, to make other women feel confident about their skills and expertise.”

Camilla is also a keen dancer, and does ballet every week, as well as trying out different dance classes on the weekend.

“I started doing ballet when I was three, and I’ve kept going ever since. I worked for a professional dance company in Italy while I was doing my PhD, but since moving to London, I just do it for fun. People tend to be a bit shocked when I tell them I’m a scientist and a dancer. The two don’t naturally go hand in hand, so I think there’s always a bit of intrigue around it.”

“Back home in Italy, there was sometimes an assumption that if you were doing a hobby outside of your job, you weren’t giving enough importance to your role, but I think my dancing actually helps me at work. Taking those 90 minutes to dance helps to shut my brain down and start afresh. It also helps me to remember that I’m not just a scientist, but I’m a person too. I want to enjoy life. If an experiment fails in the lab, it’s easy to feel black, but dancing takes me out of that.”

“I think the ballet training deeply shaped my personality and impacted on the way I approach the job I do. If something doesn’t work, I was taught that perseverance will pay off. Now, I never give up on an experiment until I’ve tried everything I can to make it work.”

Dani Chattenton - cancer bioengineer and competitive runner

Dani Chattenton is a PhD student in the Cancer Research UK Convergence Science Centre, a strategic partnership between Imperial College London and the ICR. Her research focuses on diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) – an essentially untreatable brain cancer in children.

DIPG has a 9-month median survival rate, partly due to our current inability to deliver drugs to the brain. Dani’s PhD is highly collaborative and split between four teams at the ICR and Imperial - one at Imperial and three at the ICR.

Dani’s research team at Imperial developed an ultrasound technique for drug delivery to the brain, and for the past 18 months, Dani has been working on a project to develop a similar ultrasound system at the ICR, allowing the team to test drug delivery in DIPG mouse models developed at the ICR.

She said: “The collaborative nature of this project is unique to the ICR, compared to other institutions I have worked at. The team environment ensures rapid progress of new therapeutics for defeating cancer.”

She also runs competitively and has represented Great Britain and England over 1500 m - 10 km. She said: “People always think it’s very cool that I’m working in cancer research. And they are often impressed and surprised as to how I manage to fit everything in.”

She describes how her running helps her as a scientist: “Running provides an outlet to research and structure to my day. I’ll have a set amount of time each day to complete my work before I have to go training, this makes me efficient and productive with my time. When I’m not running I become less productive and spend longer doing the same amount of research work. Aside from this, competitive sports teach you to be resilient and work hard which are important values that can be transferred to research.”

Ana Padilha - cancer biologist and baker

Dr Ana Prim Padilha is a Higher Scientific Officer in the Translational Therapeutics team, led by Dr Adam Sharp. She is learning more about the biology of advanced prostate cancers with the goal of improving the therapies available to people.

Ten years ago, Ana completed her Masters project at the ICR before moving to Cardiff to start a PhD. After completing it, she returned to the ICR to join a new lab.

“When I returned to the ICR, Adam was just starting his lab. There were only three of us at that point and I was the only woman. I’ve always been supported and never felt less for being a woman or for not being British. I always felt valued and encouraged.” She said: “I feel very lucky to be part of this team.”

“When I meet new people, they tend to be very impressed when I tell them I’m a scientist. I don’t think it’s because science is regarded as a ‘male profession’, I think it’s actually because of Covid-19. The past two years really did shine a spotlight on research and how it directly impacts people’s lives. It has helped people realise how valuable our work can be.”

Outside of the lab, Ana loves to spend time in the kitchen. As a seasoned cook and baker, she sees a crossover between baking and research – but also notes key differences.

“You could say I really like to experiment in the kitchen – baking and cooking are my biggest hobbies. I'm actually not very good at following recipes, so for me, baking and cooking are creative activities.

“Although science can be creative, as a scientist, I have to follow protocols most of the time. But when it comes to experimenting in the kitchen, I have total freedom. For me, that's the fun part of the kitchen and why I’ve always loved baking and cooking: the freedom in the creative process.

“Just before starting my PhD seven years ago, I was diagnosed with coeliac disease and had to adapt my diet, which was a massive lifestyle change. But because I already had a passion for baking and cooking, I saw it as an opportunity to carry on experimenting and came up with many gluten-free creations. I even started an Instagram account to share recipes.”

Every year for International Day of Women and Girls in Science, and International Women's Day, we shine a spotlight on some of the many fantastic women leading the way at the ICR.