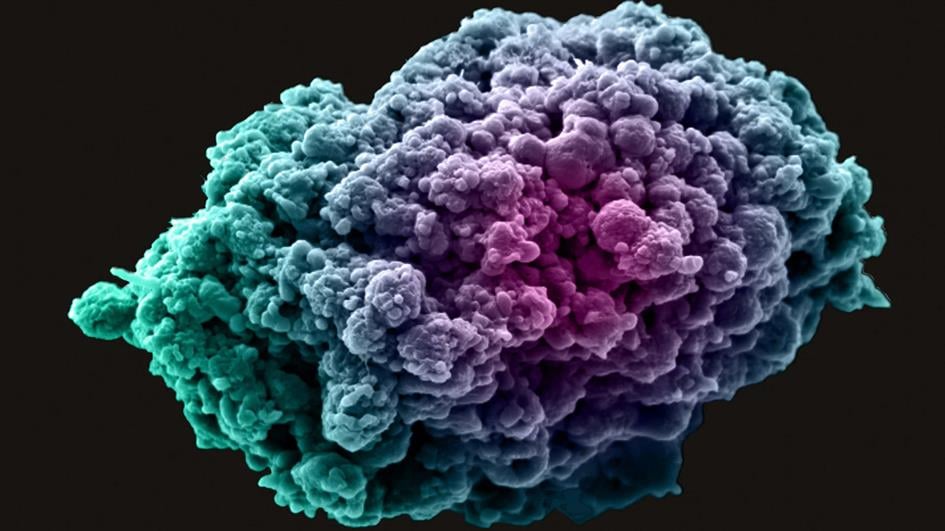

Image: Breast Cancer Cell Spheroid. Credit: Khuloud T. Al-Jamal, David McCarthy & Izzat Suffian. CC BY 4.0

The Institute of Cancer Research, London, is urging NHS-England, NICE and pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca to continue discussions after the disappointing decision not to recommend targeted drug olaparib for women with early-stage, high-risk, inherited breast cancer.

Olaparib cuts the risk of cancer recurrence and improves survival when added to standard treatment for people diagnosed with high-risk early-stage breast cancer who have inherited faults in their BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes – faults now routinely detected through NHS breast cancer and family history genetics clinics.

Miss out on cutting-edge treatment

The draft decision, announced by NICE, means people diagnosed with these forms of early-stage, inherited breast cancer in England and Wales will not yet have access to a cutting-edge treatment that targets the specific biology of their cancer to help them remain free of cancer long term and improve their overall survival.

The decision follows unsuccessful attempts to widen access to olaparib – a drug developed through UK-led and funded science – for a range of cancers linked to BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations, including advanced prostate cancer and advanced breast cancer.

The ICR believes widening access to olaparib will rely on successful negotiation between commercial partners, NHS-England and NICE – to agree a pricing structure which is affordable for the NHS and commercially viable.

One of the barriers has been the difficulty in allowing flexibility in the price of drugs for new indications where the drug is already on the market.

The ICR believes it is essential a solution is found as soon as possible, not only for patients with early-stage breast cancer and BRCA mutations, but also for people with prostate cancer and particular mutations in their tumours.

The ICR leads works to influence policy development high-priority areas to help ensure people with cancer can access the latest treatments as quickly as possible. Find out more about our position on how cancer drugs are priced.

Read more

Exploits a weakness in cancer cells

Olaparib targets the specific biology of the BRCA genes, exploiting a weakness in cancer cells while leaving healthy cells much less affected. The ICR worked with many partners including Breast Cancer Now, Cancer Research UK and industry partners to discover how to use olaparib and other PARP inhibitor drugs for people with mutations in their BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, or faults in other DNA repair genes.

Researchers from the ICR and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust then led early clinical trials assessing the benefits of olaparib against cancers with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Professor Andrew Tutt from the ICR is lead Principal Investigator and chair of the steering committee for the international phase III OlympiA Trial, coordinated globally by the Breast International Group, which showed the benefits of olaparib for improving early breast cancer survival, and has led to the licensing of olaparib in this context in many countries globally.

Life-changing drug

Professor Andrew Tutt, Professor of Oncology at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and King’s College London, said:

“Olaparib is a life-changing drug for patients diagnosed with this kind of inherited early-stage breast cancer. That is why it has achieved a license in many countries, including the UK, and is recommended by independent international clinical guidelines groups. Today’s decision is a missed opportunity to help more people remain cancer free after treatment, live well and survive breast cancer.”

“I would urge the manufacturer, NHS-England and NICE to agree a price for olaparib that is affordable for the NHS and is structured flexibly enough to be commercially viable.”

'A disappointing decision'

Professor Kristian Helin, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

“This is a disappointing decision that will deny people with inherited breast cancer access to a personalised treatment that can improve their survival and help keep them free of cancer in the long term.

“It’s the latest instance where it has not been possible to make olaparib available for people with cancer at a price that the NHS can afford, and it points to wider failings in how we agree drug pricing in England and Wales.

“Targeted drugs like olaparib, which exploit specific faults in cancer and are effective across multiple cancer types, are being held back by out-dated single-price systems. We urge NHS-England and NICE to consider more flexible models of drug pricing, which would allow price to vary depending on a drug’s use, while providing reassurance that new treatments will deliver on their promised benefits. These discussions must go ahead with urgency – for every day that access to olaparib is restricted, people with cancer will lose their lives or see a cancer that could have been suppressed, return.”