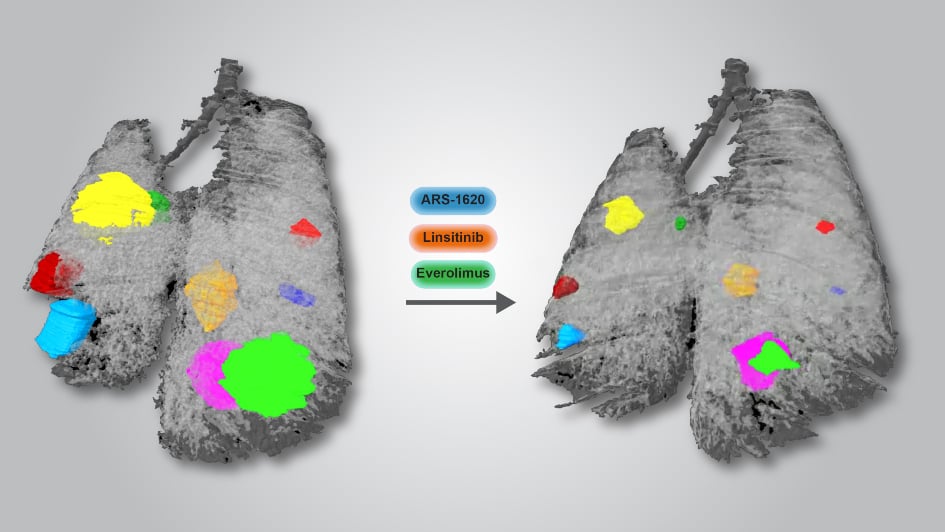

Image: Mouse lung before and after treatment with the new three-drug approach. Each colour represents a different tumour. Image credit: Miriam Molina-Arcas, Francis Crick Institute.

Combining a new class of drug with two other compounds can significantly shrink lung tumours in mice and human cancer cells, finds a new study led by the Francis Crick Institute and The Institute of Cancer Research, London.

The study, published in Science Translational Medicine, looked at G12C KRAS inhibitors. This new type of drug targets a specific mutation in the KRAS gene that can cause cells to multiply uncontrollably and lead to fast-growing cancers.

These mutations are found in 14% of lung adenocarcinomas, the most common form of lung cancer. There are still no effective treatments for most patients, and more than eight in ten will die within five years of diagnosis. Every year, around 2,800 people in the UK will develop lung cancers with the deadly G12C KRAS mutation.

Our pioneering drug discovery research is transforming the lives of cancer patients across the world. We are building a state-of-the-art Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery, where we will create more and better drugs for cancer patients.

Find out more

Combining drugs to prevent resistance

Drugs targeting G12C KRAS mutations are showing promising anti-tumour activity and few adverse effects in US clinical trials, but it is unclear how long any response will last before the cancer becomes resistant.

"It's likely that tumours will develop resistance to the new drugs, so we need to stay one step ahead," explains senior author Professor Julian Downward, who led the research at the Crick and ICR. "We found a three-drug combination that significantly shrank lung tumours in mice and human cancer cells. Tumours treated with the combination shrank and stayed small, whereas those treated with the G12C KRAS inhibitor alone tended to shrink at first but then start growing again after a couple of weeks. Our results suggest that it would be worth trying this combination in human trials in the coming years, to prevent or at least delay drug resistance."

The other compounds in the combination block the mTOR and IGF1R pathways, both of which have been previously tested in cancer patients. There are already licensed mTOR inhibitors on the market, while IGF1R inhibitors are still at the trial stage.

Targeting genetic mutations to block cancer survival

To develop this combination, the team used tumour cells derived from patients with the G12C KRAS mutation. They edited these cells to block the activity of 16,019 different genes and treated them with compounds that KRAS mutant cancers are known to be susceptible to.

"We found that cell lines without the MTOR gene were significantly more vulnerable to both KRAS and IGF1R inhibitors," explains first author Dr Miriam Molina-Arcas, Senior Laboratory Research Scientist at the Crick. "When we blocked all three pathways, the mutant cancer cells were simply unable to survive. This makes it a promising avenue for human trials in the coming years, although this is still early research. Promising results in mice and cells can tell us what's worth trying, but it's impossible to predict how patients will respond until we actually try."

Promise of outsmarting cancer

Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, explained:

“This study shows that, by combining three different cancer drugs, their anti-tumour activity is boosted in models of lung cancer.

“Cancer’s ability to evolve and resist treatment is the biggest challenge we face in defeating the disease. A major part of the answer will lie in combination treatment, using drugs with different mechanisms of action together to block potential evolutionary pathways.

“Combination treatments like the one used in this study are a vital part of the ICR’s ambitious strategy to understand cancer’s complexity and evolution – and to overcome evolution and drug resistance through the world’s first ‘Darwinian’ drug programme in our new Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery.

“We are investing an initial £75 million in creating a global centre of expertise in anti-evolution therapies such as these, which hold the promise of outsmarting cancer to improve cure rates."