-embed.jpg?sfvrsn=5c3f7969_0)

Colorised scanning electron micrograph of a macrophage (image: NIAID/CC BY 2.0)

Cancer has been described as a wound that doesn’t heal. Despite cancer treatments designed to trigger the machinery that causes cells to die, researchers have known for decades that cancer cells which survive treatment can rapidly repopulate tumours by proliferating at a much higher rate than healthy cells.

When the body suffers an injury, the immune system leaps into action, like the emergency services at the scene of an accident; clearing up dead and dying matter and encouraging cells to divide nearby to replace the damaged tissue.

This capacity to self-repair is truly amazing, but it could also help cancer stem cells to grow out of control or tumours regrow after therapy.

Researcher Dr Pascal Meier and his team at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, are investigating these mechanisms to understand how they might affect treatment and recovery in patients with cancer.

In the journal Current Biology, Dr Meier discusses how dying cells communicate with their healthy neighbours to encourage regrowth after injury.

Using ‘zombie’ fruit fly cells which were kept in a permanent state of dying, researchers saw that dying cells produce a compound called hydrogen peroxide, through the activity of proteins called caspases.

Early warning system

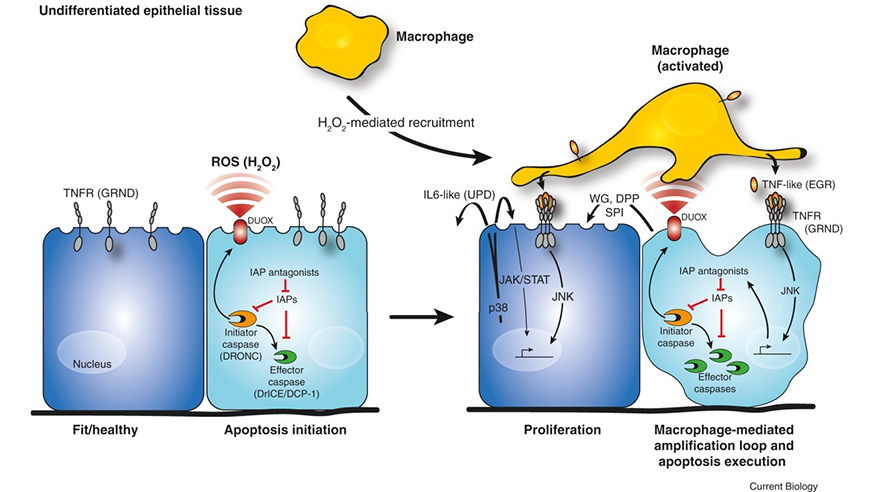

Caspases carry out important inflammatory responses such as apoptosis, or programmed cell death, and ensure that cellular components are degraded in a controlled manner. In the dying cells the production of hydrogen peroxide acts as an early warning of damage for the immune system, triggering a cascade of signalling that starts wound healing.

Inflammation triggers a feedback loop which replaces malfunctioning cells, by activating signalling in both healthy and dying cells. The findings could help explain how cancer regrows after treatme (image: Current Biology)

White blood cells called macrophages are recruited by the cells, which engulf and digest cellular debris, foreign substances, cancer cells or anything else without the right types of proteins on their surfaces.

These macrophages activate a signalling mechanism called JNK that creates a feedback loop producing more and more signals telling the cells to die.

But interestingly, JNK also has an effect on the neighbouring healthy cells, leading them to produce compounds that encourage cell division and tissue repair.

Normally this process works correctly to keep healthy tissue replenished, but in cancer it helps tumours recover after treatments like radiotherapy and chemotherapy, causing cells to spread rapidly.

This dual role in clearing away damaged cells and re-growing tissue to compensate helps cancer to survive therapies designed to destroy it, but it could also point the way to improving treatment in the future.

Rewiring defences

Professor Meier and his team are studying inflammation in breast cancer, to see how these cells communicate with their neighbours when they are dying.

If they can identify the signalling receptors that coordinate inflammation in breast cancer cells, they could prevent this resistance to common cancer treatments and stop tumours regrowing via their healthy neighbours.

They hope that rewiring the macrophages recruited by cancer cells could switch off the signals that encourage cancer cells to proliferate.

They are also investigating a similar phenomenon called cell competition, where stronger cells kill weaker cells, which may play an important role in the development of cancer.

A complex relationship exists between cell death and inflammation — our body’s response to damage and infection — but understanding this relationship could help doctors treat cancer more effectively.

comments powered by