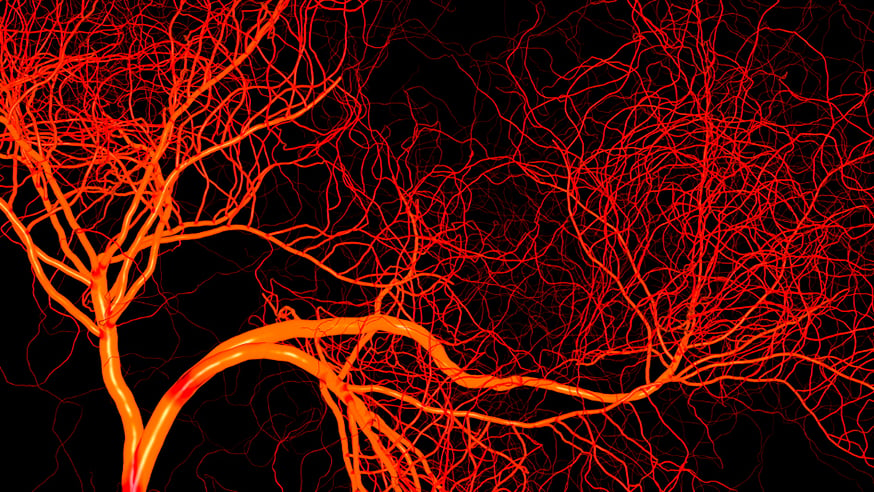

Blood vessels illustration (photo: Inozemtsev Konstantin/Shutterstock.com)

New research into breast and bowel cancers that have spread to the liver shows that some tumours power their growth using pre-existing blood vessels rather than developing new ones.

The results help to explain why existing treatments which block the development of new blood vessels have so far failed to have the desired effect of slowing the growth of secondary breast cancer tumours, according to a major new paper published today in the journal Nature Medicine.

The researchers believe their findings could also be applicable to a range of cancers that have the potential to spread to the liver and other sites.

Breast Cancer Now-funded scientists in The Institute of Cancer Research, London, looked at whether secondary breast and bowel cancers occurring in the liver used pre-existing blood vessels to grow, known as vessel co-option, or grew new blood vessels, a process called angiogenesis.

Exploiting blood vessels

Previously, scientists thought all cancers needed to establish new blood vessels in order to grow, and several anti-angiogenesis drugs have been developed to block this process.

The researchers, working within the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at the ICR, studied clinical samples of secondary tumours occurring in the liver of breast cancer and bowel cancer patients.

Using 187 samples from 92 bowel cancer patients, who received treatment with the anti-angiogenesis drug Avastin (also known as bevacizumab) before having their liver tumours removed, the researchers found that around 40% of the secondary tumours obtained a blood supply predominantly through vessel co-option, while the remaining tumours relied more on angiogenesis or used a mixture of angiogenesis and vessel co-option. They also showed, for the first time, that the tumours which mainly used vessel co-option responded poorly to combined treatment with Avastin and chemotherapy.

The study also looked at secondary tumours in the liver from a group of 17 patients with breast cancer. Removing secondary breast cancers that have spread to the liver is not common practice and so these tumours have not been extensively studied in terms of how they recruit blood vessels.

Notably, the researchers found that 16 out of the 17 tumours examined used vessel co-option to obtain a blood supply. The scientists noted that other studies have shown that secondary breast tumours occurring in the brain, lungs, skin and lymph nodes can also rely on pre-existing vessels for their blood supply.

Dr Andrew Reynolds describes his group's research into how cancers can resist treatment by ‘stealing’ blood vessels from nearby tissues in this video from April 2016.

Blocking the process

Researchers also looked at whether it was possible to block the vessel co-option process in secondary tumours occurring in the liver, and combined this approach with an anti-angiogenesis drug, to test the potential of a two-pronged approach to treatment.

Using mice, they found that when they ‘switched off’ a gene which helps cancer cells to move towards existing blood vessels and co-opt them, and then treated the tumours with an anti-angiogenesis drug, there was significantly less tumour growth than treating tumours with the anti-angiogenesis drug alone.

Dr Andrew Reynolds, who led the research and is a Team Leader in Tumour Biology at the ICR, said: “It was thought for a long time that cancers that have spread to the liver must generate new blood vessels to thrive — but now we’ve shown that they can piggy-back on pre-existing vessels instead.

"Our work helps to explain why drugs designed to target new blood vessel growth in secondary tumours do not always work as well in patients as was originally hoped for. And we found that this use of pre-existing vessels was especially common in breast cancers that had spread to liver.

“We now need to undertake more research to understand exactly how tumours recruit pre-existing blood vessels. Our study has suggested that drug combinations that block both vessel co-option and angiogenesis could potentially offer hope as future treatments, and I look forward to this possibility being explored in follow-up studies.”

More effective treatments possible

Baroness Delyth Morgan, Chief Executive at Breast Cancer Now, said: “This research shows how breast cancers use patients’ pre-existing blood vessels in order to grow after they have spread to different parts of the body. It could lead to the development of new, more effective treatments for the disease.

“Secondary breast cancer is currently incurable, so research that gives us new hope by helping us understand how secondary tumours develop and thrive is a powerful tool in the battle against this disease.

“If we are to reach our goal of ensuring that by 2050, all those who develop breast cancer will live, we need to build a picture of how the disease thrives after it spreads away from the breast, and use this to develop new therapies.”

The research also received NHS funding to the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and the ICR, as well as support from the Liver Disease Biobank (Montreal), De Stichting tegen Kanker (Antwerp). Breast Cancer Now funding includes support from Avon through the ‘Dr Avon’ Clinical Fellowship scheme.

The research was a multidisciplinary collaboration, led by Dr Reynolds from the ICR, and involved an international team of scientists, including Professor David Cunningham from The Royal Marsden Hospital (London), Professor Peter Metrakos from McGill University Health Centre (Montreal) and Dr Peter Vermeulen and Professor Luc Dirix from GZA Hospitals St. Augustinus (Antwerp) who all provided tumour samples from patients for the study.