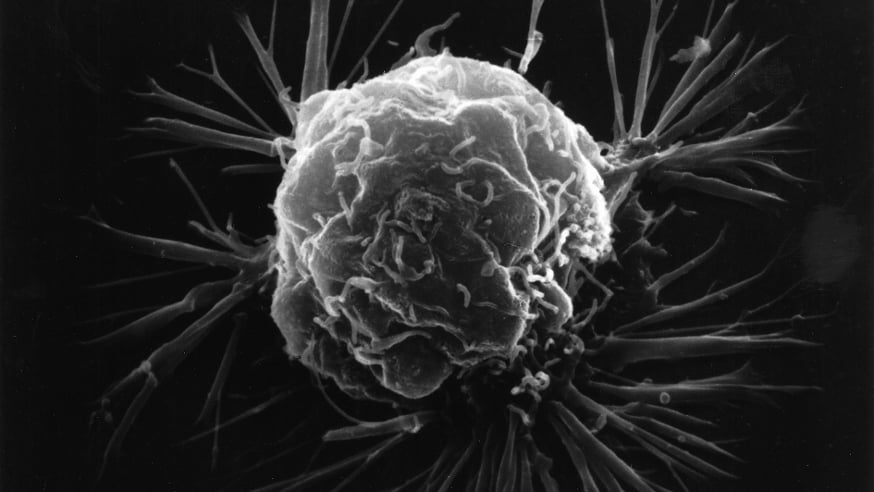

Breast cancer cell photographed by an electron scanning microscope. Source: National Cancer Institute. License: Public domain.

Researchers have discovered that an amino acid called asparagine is essential for breast cancer spread, and by restricting it, cancer cells stopped invading other parts of the body in mice.

Most breast cancer patients do not die from their primary tumour, but from the spread of cancer to the lungs, brain, bones, or other organs. To be able to spread, cancer cells first need to leave the original tumour, survive in the blood as ‘circulating tumour cells’, and then colonise other organs.

Finding ways to stop this from happening is fundamental to increasing survival.

Link between amino acid and survival

Researchers at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, working with colleagues at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, found that blocking the production of asparagine in mice with a drug called L-asparaginase, and putting them on a low-asparagine diet, greatly reduced the breast cancer’s ability to spread.

Asparagine is an amino acid – the building blocks that cells use to make proteins. While the body can make asparagine, it’s also found in our diet, with higher concentrations in some foods including asparagus, soy, dairy, poultry, and seafood.

Researchers were prompted by these mouse studies to examine data from breast cancer patients. These data indicated that the greater the ability of breast cancer cells to make asparagine, the more likely the disease is to spread.

In several other cancer types, increased ability of tumour cells to make asparagine was also found to be associated with reduced survival.

The research had multiple funders, including Cancer Research UK, the National Institutes of Health, and the ICR, and was published in the journal Nature today.

Restricted diet as a treatment

Professor Greg Hannon, lead author of the study based at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, said:

“Our work has pinpointed one of the key mechanisms that promotes the ability of breast cancer cells to spread.

“When the availability of asparagine was reduced, we saw little impact on the primary tumour in the breast, but tumour cells had reduced capacity for metastases in other parts of the body.

“This finding adds vital information to our understanding of how we can stop cancer spreading – the main reason patients die from their disease.

“In the future, restricting this amino acid through a controlled diet plan or by other means could be an additional part of treatment for some patients with breast and other cancers.”

You can help fund future research leaders by supporting one of our young scientists and clinicians now.

Find out more

Using the ICR scientist's expertise

Dr George Poulogiannis, Dr Michel Wagner and PhD student Marc Olivier Turgeon worked on the research that took place at the ICR. They designed and carried out studies to measure the levels of asparagine in different tissues within the mice before and after treatment with the L-asparaginase drug.

This work relied on the team’s expertise in analysing the metabolic processes that take place in cancer cells. Study co-author Dr George Poulogiannis, leader of the Signalling and Cancer Metabolism team at the ICR, said:

“A better understanding of the nutrients that help fuel cancer’s spread is important if we’re going to find new ways to slow the process down and possibly stop it.

“These exciting findings provide the foundation for research into an entirely new type of cancer treatment that targets the metabolism of tumour cells to control their growth and spread.”

Developing better treatments for breast cancer patients

Professor Charles Swanton, Cancer Research UK’s chief clinician, said:

“This is interesting research looking at how cutting off the supply of nutrients essential to cancer’s spread could help restrain tumours.

“Interestingly, the drug L-asparaginase is used to treat acute lymphoblastic leukaemia which is dependent on asparagine. It’s possible that in future, this drug could be re-purposed to help treat breast cancer patients.

“The next step in the research would be to understand how this translates from the lab to patients and which patients are most likely to benefit from any potential treatment.”

Martin Ledwick, Cancer Research UK’s head nurse, said:

“Research like this is crucial to help develop better treatments for breast cancer patients. At the moment, there is no evidence that restricting certain foods can help fight cancer, so it’s important for patients to speak to their doctor before making any changes to their diet while having treatment.”