Image: BRCA2 researchers group photo from December 1995 (Courtesy of Dr Richard Wooster)

In December 1995, a team of researchers published a paper identifying the second breast cancer susceptibility gene, better known as BRCA2. This discovery transformed the field of cancer research, leading to genetic testing in breast, ovarian and prostate cancer and then PARP inhibitors for all three, and has had an impact on many people’s lives.

The gene discovery was led by a team of researchers who were then working here at The Institute of Cancer Research, London. The team had major funding from Cancer Research UK and support from Breast Cancer Now.

There are more than 40 co-authors on the paper published in Nature from institutes and universities around the world. At the ICR these included the leader of the team, Professor Sir Mike Stratton, who is now Director of the Wellcome Sanger Institute, and Alan Ashworth, who later became the CEO of the ICR and is now President of the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center and Senior Vice President for Cancer Services with UCSF Health.

As we celebrate the 25th anniversary of the BRCA2 gene discovery, we want to recognise the passionate team behind the research. They worked day and night in a race to discover the gene and their work continues to have a lasting impact. Here are the stories of three of the team members from the ICR labs who made this discovery possible 25 years ago.

Dr Richard Wooster: How we won the race

In 1995, Richard Wooster had recently joined Mike Stratton’s lab as a postdoc. He was struck by the ICR’s previous work identifying breast cancer families and could see the potential to identify the gene that was causing their cancers.

On the heels of the BRCA1 gene discovery in 1994, there was a real sense of excitement and competition. Myriad Genetics had found and patented the BRCA1 gene and the next logical step was they would look for other breast cancer genes.

“It was clearly a race,” recalls Wooster. “I would say they had an advantage because they've been through this once. So a lot of our thinking was how can we not just be in the race, but how would we win the race.”

Working in temporary buildings in Sutton, the ICR was part of the underdog team. But what our researchers lacked in resources they more than made up for with drive and the belief that this information should be freely available to help patients.

Once the ICR team mapped the gene to part of chromosome 13, they faced a dilemma. The Wellcome Sanger Institute would be able to sequence this part of the chromosome, but as soon as its researchers did so the DNA code would enter the public domain and be accessible to competing teams searching for the gene.

“After that genome sequence became available. I remember sitting with Alan Ashworth in his office and he was going through the DNA sequence and translating it by hand as a way to look for where the gene might be,” says Wooster.

The team set to work rapidly screening the DNA from patients in the breast cancer families looking for relevant mutations. In most cases, the sequences came back with silent changes. When they found the first potentially disease-causing mutation, it was a eureka moment. They focused on this particular gene, which would come to be known as BRCA2. As they looked closer, they found more and more mutations on the gene in different families.

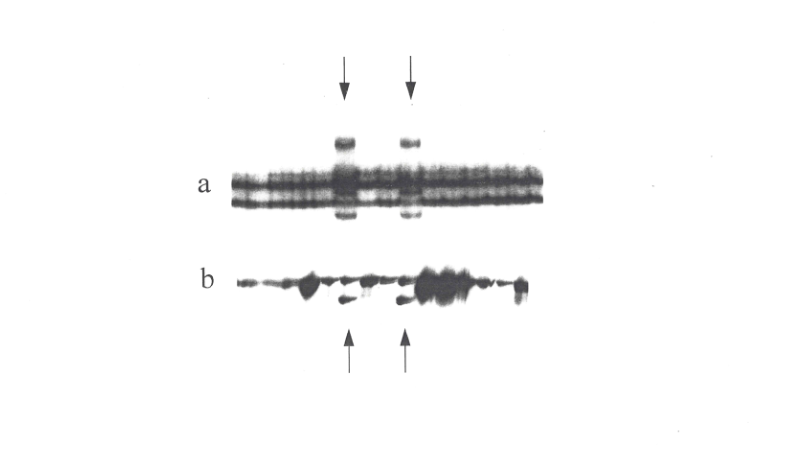

Image: A slide showing abnormalities in the BRCA2 gene (Courtesy of Dr Richard Wooster)

Looking back on that moment 25 years later, Wooster says: “That feeling of how you can help people is pretty incredible. And just working as part of a team is great fun. But you can also achieve pretty amazing things.

“This wasn't any one individual who brought all of this together. It was the team of scientists with this shared passion and desire to win the race.”

Dr Richard Wooster is the Chief Scientific Officer of Translate Bio.

Sally Swift: ‘The race between giving birth and finding a gene’

In April 1995, Sally Swift had two pieces of good news for her boss Alan Ashworth.

First, she had mastered an incredibly complex and untested technique. Swift was a technician known for her ‘magic touch’ in the lab and after several months of pipetting she had successfully precipitated a piece of DNA that would help on the road to discovering the BRCA2 gene.

“During that time, I also found out that I was pregnant. I had quite a lot going on,” recalled Swift.

Swift describes the months that followed as ‘absolute hard graft’. The team entered a routine of coming in, picking colonies, growing them up, extracting the DNA, sequencing it and sending vast amounts of data to Richard Wooster and Mike Stratton working in a separate ICR team in Sutton.

As the end of the year drew closer, the team was made very aware that there was a company in the US taking a very similar approach.

Swift says: “There was a bit of a race going on there. I was getting bigger and bigger and it was always the joke: Would we find the gene before Sally had her baby?”

In December 1995, the team discovered the gene. In early January, Swift’s son was born. In February, she joined the team for a celebratory dinner at L’Escargot in London for her first night out after having a newborn.

Since then, Swift has continued to work in what is now the ICR’s Division of Breast Cancer Research, and Breast Cancer Now Research Centre, as a Higher Scientific Officer and now as Lab Manager.

Her son will be turning 25. During his studies, he came across her role in the BRCA2 discovery.

Swift says: “I don't think he actually realised what his mum had done, particularly when I was carrying him.

“I don't think I will ever forget the fact that I was part of that team, because it's massive. But I also feel just so lucky. I mean, it doesn't really get much better than finding a gene that's going to make such a massive difference in people's lives.”

Sally Swift is the Lab Manager of the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at the ICR.

Rita Barfoot: ‘Her name will live on in that paper’

Rita Barfoot’s daughter doesn’t remember seeing a lot of her mum during the weeks and months leading up to the BRCA2 gene discovery.

“They were literally working seven days a week. I’d get up and she was gone,” recalled Rita Barfoot’s daughter Regan.

In 1995, Rita joined Professor Mike Stratton's team to work on a project entitled 'Isolation of the BRCA2 gene'. It was highly confidential so Regan didn’t know what her mum was working on but she could tell it was important and that they were getting close.

At the time, many of the samples had to be processed manually. Rita would head to the lab early and work late as the team split shifts to keep gels running 24/7. Rita would also double and triple check everything was perfect. Regan notes her mother managed this incredible output even though she was in her 50s and ‘no spring chicken’.

It was a lot of hard work, but never a hardship. The lab was filled with laughter, especially from Rita who had a wicked sense of humour. The entire team was incredibly passionate, driven and supportive of one another.

“This was team science with a capital T. Everyone pulled their weight to get the paper out,” Regan said. “And her name will live on in that paper.”

Rita worked at the ICR for 43 years in several labs and training the next generation of researchers before retiring in June 2010. She was appointed as an Associate of the ICR in recognition of her long service and contributions to the ICR. She died in October 2019.

If Rita were here to mark the 25th anniversary of the BRCA2 discovery, Regan says her mother would probably say “Is it that long?” and then go on PubMed to check what clinical impact it had continued to have.

Regan said: “I’m proud of everything mum achieved, and there’s an awful lot. She gave her entire career and passion to the ICR.”

Regan is Rita Barfoot's daughter.

The BRCA2 gene discovery enabled families with a history of certain cancers to be assessed for future risk, and laid the groundwork for developing novel forms of therapy for BRCA-associated cancers. Learn more about our research related to BRCA genes:

Find out more