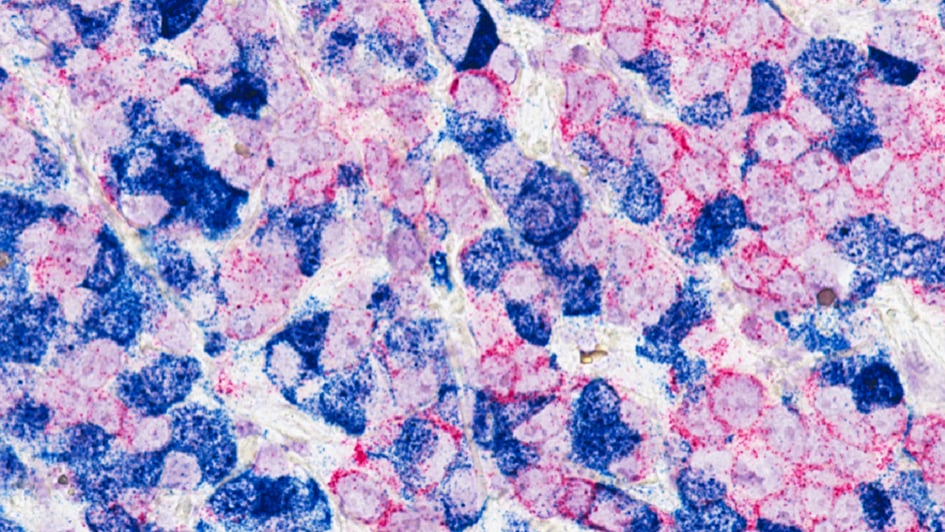

Image: Human breast cancer cells implanted in an experimental animal with two different tracers (red and blue) to investigate the interaction of tumour cells. Credit: Min Yu, National Cancer Institute

Removing a single protein from cells that surround tumours can improve the sensitivity of certain cancers to immunotherapy, researchers have found.

Scientists from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, in collaboration with AstraZeneca removed, in mice, a receptor protein called Endo180 found on cancer-associated fibroblasts, cells that can help breast cancer to grow and spread, which boosted treatment response. Analysing patient data, they found that targeting this protein in cancer patients could improve the effectiveness of immunotherapy in breast cancer.

Unpacking the tumour ecosystem

Rather than being made solely of tumour cells, cancers contain a complex ecosystem of various cell types they draw on to help them survive. Investigating this tumour microenvironment opens the door to new treatment possibilities, and means scientists could target more than just cancer cells to treat the disease.

This ties into the ICR’s new strategy, which plans to unravel and disrupt cancer ecosystems by directing research against the cells, signals and immune responses in the tissue environment that nurtures tumours.

Immune cells are one example of non-cancerous cells found in the tumour microenvironment. Immunotherapy aims to harness them, boosting the body’s own immune system to destroy tumours. A relatively new treatment, it can lead to a strong, long-lasting response in patients.

Unfortunately, not all patients respond well to immunotherapy – including those with breast cancer, and attention has turned to ways to change this. The study, published in Cancer Research, shows that targeting another non-tumour feature of the microenvironment could enhance the response of immunotherapy in patients who were previously insensitive to it.

Fibroblasts make tumours ‘immune cold’

Funded by Breast Cancer Now and a BBSRC iCASE studentship, which involved the first author spending time at pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca as part of their PhD, the research focuses on cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) – structural cells which, when recruited by cancers, support tumour growth.

Patients with CAF-dense tumours, which is often the case with breast cancer, rarely respond well to immunotherapy, and the researchers interrogated why this may be the case.

The team, led by Professor Clare Isacke, Professor of Molecular Cell Biology in the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at the ICR, modelled the disease in two different groups of mice – those with and without high numbers of cancer-associated fibroblasts in their tumours – and compared them in parallel.

This innovative method found that CAFs prevent a type of cancer-killing immune cell called CD8+ T cells from entering tumours. A tumour microenvironment without many immune cells within it is described as ‘immune cold’, and this explains why fibroblast-rich cancers rarely find success with immunotherapy – because there aren’t enough immune cells within the tumour to trigger a response.

The Endo180 Receptor

The researchers linked this lack of immune cells with the presence of the Endo180 receptor, which CAFs have a high number of. They found that removing Endo180 from mice reversed the ‘immune cold’ microenvironment, and that mice not only had more CD8+ T cells in their tumours, but they also showed increased sensitivity to immunotherapy.

The team analysed data from melanoma patients, and they found that MRC2, the human equivalent of the Endo180 gene, is more abundant in those who were insensitive to immunotherapy. This suggests that MRC2 may have a significant role to play in mediating response to immunotherapy in humans, so reducing its expression could potentially improve outcomes for patients.

Immunotherapy has the ‘potential for cure’

Professor Clare Isacke, Professor of Molecular Cell Biology at the ICR, said:

“Immunotherapy is going to be here for a long time. It doesn’t work for everyone, but it actually has the potential for cure, which is not a word that we tend to say very much in cancer. Our aim is to make it a viable option for more patients.

“Lots of people are saying cancer-associated fibroblasts are bad when it comes to immunotherapy, but this is one of the first experiments, using knockout mice, that’s tried to do something about it.”

‘A novel approach’

Dr Liam Jenkins, recipient of the BBSRC iCASE PhD studentship at the ICR, and first author of the study, said:

“There’s already a lot of interest in using antibodies to target proteins and enhance treatment response, but these generally focus on cancer cells. Instead, we’re taking a novel approach by targeting other cells in the tumour microenvironment.

“These findings, in mice, are promising and offer more proof that cancer associated fibroblasts contribute to insensitivity to immunotherapy, and if you can modulate these by targeting Endo180, or its equivalent in humans, you can improve immunotherapy response. When immunotherapy works, it’s normally a durable response, which is the beauty of it.”